Take a fascinating tour through the Codex Atlanticus, a remarkable collection of writings and paintings by Leonardo da Vinci. This collection, with 1119 papers filled with illustrations, technical insights, and even stories, is the biggest source of the Renaissance master’s original ideas that are currently available. Sculptor Pompeo Leoni put it together and covered the entirety of Leonardo’s career, providing a rare glimpse into his creative development from Tuscany to France. The Codex Atlanticus, from its misidentification as a Chinese manuscript during Napoleon’s reign to its present home in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana, illustrates the complexity of da Vinci’s varied intellect and the brilliance of his mind.

1. Largest Collection of Leonardo’s Drawings and Notes

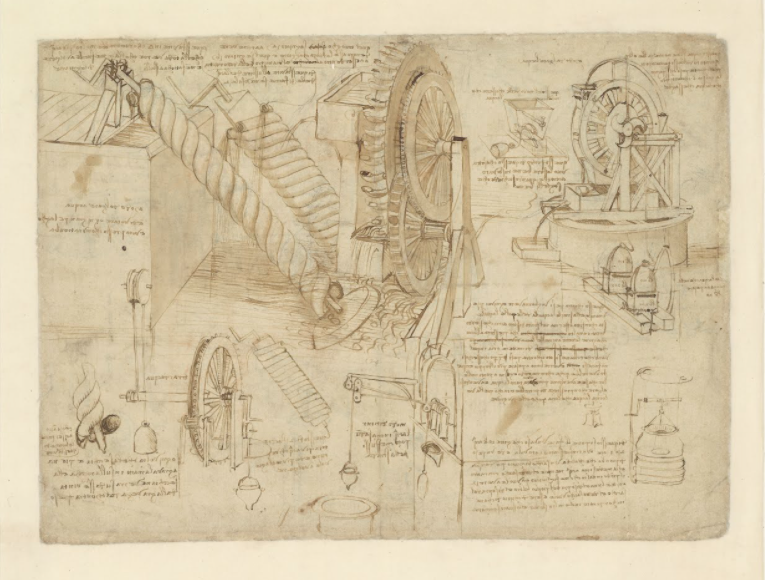

The Codex Atlanticus is the most extensive compilation of Leonardo da Vinci’s original drawings and written notes, totaling 1119 papers, often containing content on both sides.

2. Assembled by Pompeo Leoni, Not Leonardo

Milanese sculptor Pompeo Leoni, in the late 16th century, assembled the Codex Atlanticus from papers retrieved from Leonardo’s pupil, Giovan Francesco Melzi. Leoni created two volumes, one focused on technical-scientific themes (Codex Atlanticus) and the other on anatomy and artistic subjects (Windsor collection).

3. Named “Atlanticus” for its Size, Not Content

The name “Atlanticus” is unrelated to content but derives from the large sheets resembling those used for geographic atlases when Leoni assembled the collection.

4. Housed in Biblioteca Ambrosiana since 1637

Marquis Galeazzo Arconati donated the Codex to Biblioteca Ambrosiana in 1637. The library, founded by Cardinal Federico Borromeo, has preserved and made the collection accessible since then.

5. Spans Leonardo’s Entire Career

Covering 1478 to 1519, the Codex encompasses Leonardo’s artistic and scientific life. It includes drawings on mechanics, hydraulics, mathematics, architecture, and inventions like parachutes and war machines.

6. Taken to France by Napoleon

Napoleon took possession of the Codex in 1796 after conquering Milan. It remained in the Louvre for 17 years until the Congress of Vienna in 1815 ordered its return to Milan.

7. Mistaken for a Chinese Manuscript

In 1815, an emissary mistook the mirror-image handwriting of Leonardo for Chinese, but the error was corrected by the Pope’s emissary, Antonio Canova, leading to the Codex’s return.

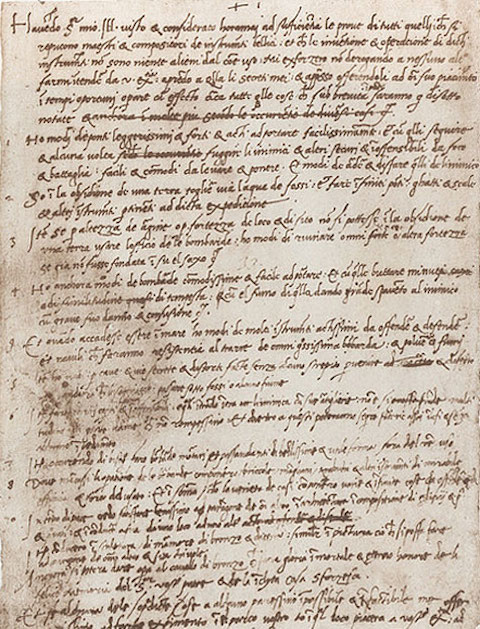

8. Includes Leonardo’s “Resume”

The Codex contains a draft letter to Ludovico il Moro, where Leonardo lists his military engineering skills in nine points, with a brief mention of his artistic abilities. Some famous military drawings in the Codex correspond to these skills.

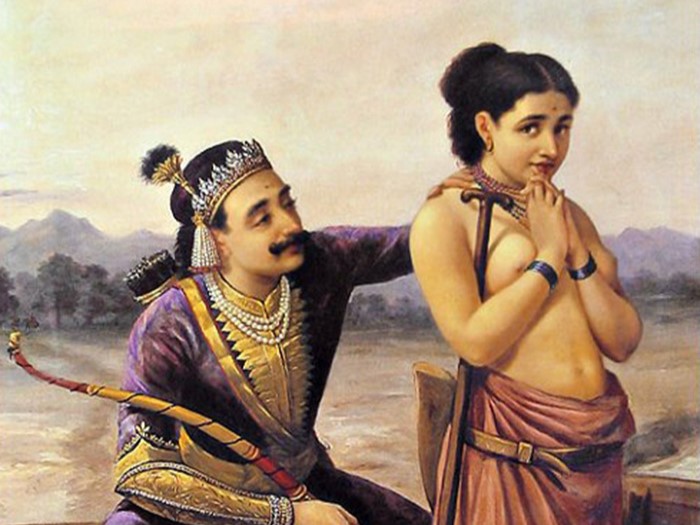

9. Features Leonardo’s Fables

In addition to technical content, the Codex includes short stories with a moral written by Leonardo. These fables often involve plants, animals, or natural elements, accompanied by lively sketches.

10. Last Dated Note

The Codex includes Leonardo’s last known dated note, mentioning his location on June 24th, in Amboise at the Palace of Cloux. He passed away on May 2nd the following year.

Feature Image Courtesy: Open Culture

The Dreams of Leonardo Da Vinci: The Vulture Fantasy From a Memory of his Childhood