Pratiksha Shome

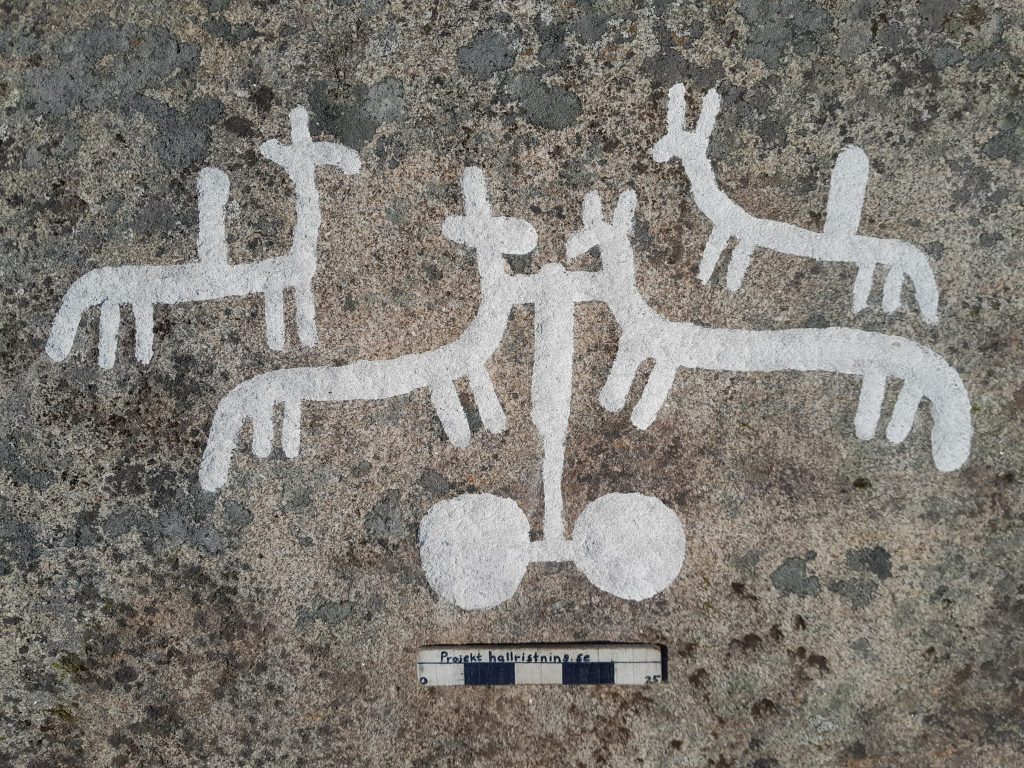

Early in May, a team of researchers combing the Bohuslän region of western Sweden discovered strange patterns on a moss-covered rock face. The crew carefully removed the plants since they appeared to be human-made and discovered dozens of rock carvings—about 40 in total—depicting ships, animals, and humans. The most recent discovery in Bohuslän, an area noted for its rock art, particularly the Bronze Age paintings at Tanum, a UNESCO site, are the rock carvings, or petroglyphs, which date back around 2,700 years. It is the greatest find made in Bohuslän this century, according to the researchers.

The freshly discovered petroglyphs were uncovered on a cliff wall that previously defined the edge of an island before sea levels progressively decreased by an estimated 40 feet over the course of several hundred years. This has prompted experts to hypothesise that the painters reached the granite surface using boats or a type of scaffolding placed on ice. In fact, in order to access the rocks and take pictures of them, the researchers working for the Foundation for Documentation of Bohuslän’s Rock Carvings constructed their own scaffolding. Stones were smacked against the granite rock laboriously to create the patterns, revealing a white underlayer underneath. Due to their size and colour, they were quite noticeable from the mainland and from passing ships.

The fact that the petroglyphs are situated three metres above the present-day ground surface is what truly distinguishes them, according to a statement from the Foundation for Documentation of Bohuslän’s Rock Carvings. “From around 700 to 800 BCE, the patterns are distributed along an even line that corresponds to the height of the sea surface. The themes fit this era’s aesthetic requirements as well. Among the most recent discoveries of petroglyphs are a 13-foot-long ship and engravings of humans, chariots, carts, and horses. Their significance is yet unclear. Although scholars believe the repeating themes carved into rocks outside the town of Kville may show they were used to convey a tale, petroglyphs were occasionally used to demarcate territory. The finding made Lennart Larsson, whose property the rock sculptures were discovered on, happy. Although I haven’t been actively seeking for petroglyphs, I find it to be a lot of fun, he said in an interview with SVT, the national broadcaster of the nation. “I can watch the ships and stick people outside from my balcony at home.”

Source: Artnet news