Manjit Bawa (1941–2008) was a pioneering Indian painter whose art brought a unique blend of modernity and tradition to the canvas. Known for his vibrant use of colours and distinctive visual vocabulary, Bawa’s works stand apart in the realm of Indian contemporary art. His paintings often drew from Indian mythology, folklore, and cultural narratives, yet he redefined these elements with a bold, simplified style that resonated deeply with modern sensibilities. Rejecting the conventions of Western realism, his art found inspiration in Pahari miniature paintings and the ethereal, dreamlike worlds of imagination. Bawa’s motifs of animals, pastoral landscapes, and mythological figures—rendered in vivid colours like greens, purples, and reds—have left an indelible mark on Indian art history.

In this essay, artist Akhilesh offers a deeply introspective analysis of Bawa’s works, unraveling layers of meaning often overlooked by traditional critiques. Through Akhilesh’s lens, Bawa emerges not just as a painter of mythological or romantic imagery but as an artist who deftly incorporates paradoxes, humor, and wit into his work. Akhilesh perceives Bawa as a “magician” of art, whose seemingly whimsical forms hold profound truths about modernity, human nature, and the contradictions of contemporary life. By exploring the nuances of Bawa’s colour palette, his reinterpretation of myth, and his ability to evoke both pathos and humor, Akhilesh paints a vivid portrait of an artist whose genius lies in crafting a world where the “thread that is not there” becomes a symbol of humanity’s lost connections. This essay delves into the essence of Manjit Bawa’s artistry, as seen through Akhilesh’s insightful observations.

(2)

Manjit’s use of colour is captivating. His palette encompasses every hue and includes all kinds of colour combinations. There is a rich blend of vibrant and muted tones in his work. Manjit’s colours arise from the soil of this land, and their paradoxical nature is evident. Without hesitation, Manjit uses green and violet, which he himself admits to having borrowed from miniature paintings. This is Manjit’s humility, attributing credit to miniature art. However, if we place miniature paintings alongside Manjit’s work, it becomes clear that his colour palette is modern and innovative.

Manjit’s understanding of a modern, free world informs his colour schemes. His endless travels, the experience of living in Europe for eight years, the solitude of the Meher Hotel in Dalhousie, and his closeness to nature—all of this finds its way into Manjit’s palette. In miniature paintings, the use of colour tends toward an excess; multiple hues are often applied together in elaborate arrangements, creating a festive celebration of colour.

In contrast, Manjit’s paintings demonstrate a restrained use of colour. He might employ multiple tones of a single red, juxtaposed against another form rendered in lighter or darker hues. In details like teeth or eyes, Manjit uses iridescent colours, showcasing his indifference to traditional colour diversity. One of Manjit’s distinguishing features is his unapologetic use of flat colour. This tendency likely stems from his training in silk screen printing. This flatness is also a refinement unique to Manjit’s art.

Manjit’s paintings are remarkable in that, while modern, they are steeped in tradition. However, Manjit does not rely on mythology to anchor this tradition; instead, he redefines it. Characters like Heer-Ranjha and Krishna-Radha are simultaneously lovers and shepherd-like messianic figures. Manjit’s use of flat colours acts as a backdrop, like hanging scrolls. His depictions of tigers, cows, cats, horses, and squirrels emerge from variations in tonal gradients.

It would not be appropriate to compare Manjit’s tonal explorations to musical notes, as music adheres to a structured raga system. Manjit’s colour tonality is whimsical and free-spirited. However, one could argue in Manjit’s favour that he was a musician himself. He had an understanding of music, particularly Sufi music. Still, claiming that Manjit’s art mirrored the discipline of musical practice would be untrue. While Manjit may not have pursued music as a discipline, the creation of forms was intrinsic to his being.

Manjit proposed a new visual idiom in Indian contemporary art, inspiring many artists to imitate him. Artists like Amitava Das, Jogen Chowdhury, and Manjit Bawa moved away from natural realism to explore the presence of the human figure. All three began around the same time, recognizing the power of imagination in art and expanding its boundaries.

Among his peers, Manjit occupies a unique position, refining his forms continuously due to their intensely intrinsic nature. Comparing his early works in this series to the paintings exhibited in 2004 reveals significant developments. Manjit embraced various challenges in this refinement, occasionally even compromising on colour.

His dialogue with his art incorporated events and changes, knowingly or unknowingly, which became vital to his visual language. Some of his works reveal linear perspectives, which are later abandoned.

Manjit’s art transcends debates of modernity versus tradition, remaining purely that of a painter. While Manjit often participated in and provoked such debates—on politics, ideology, Indian versus Western influences, or the impact of European culture—these discussions remained secondary. For him, they were like a grain of cumin in a camel’s mouth. His studio absorbed these conversations, serving as the creative centre that transported him to a wonderland where countless forms awaited him.

Manjit’s forms, colours, and lines are a testament to his presence. His paintings, with their richly coloured forms, establish a new identity for Indian painting in the ethereal space of art. Unlike the modern interpretations of Jamini Roy’s paintings, Manjit’s works demand their own unique analysis.

This makes it difficult to situate his work within the mainstream streams of modern art interpretations. Contemporary Indian art criticism lacks the comprehensive perspective needed to grasp such diversity in art. Art criticism here is often overshadowed by personal biases rather than professional rigor. The young generation of artists lacks substantial books to understand their artistic world; instead, they rely on sparse books and catalogs, offering little more than self-indulgent satisfaction.

Manjit’s artistic distinctiveness awaits a holistic artistic vision that can thread together these connections—the thread that is not there. Among all, Swaminathan stands out as the only artist capable of conveying profound ideas succinctly. Swaminathan’s writings seem to fulfill this need. He does not recognize Manjit as an artist for any political ideology or other specific reasons but for the sheer artistic essence that defines him.

In one interview, Manjit said, “As a child, painting seemed like an act of magic to me—a kind of magic that could compel a person to surrender to it.”

Manjit spent many years mastering this magic, only to realize that he himself was a magician. His paintings compel surrender in anyone who encounters them. Like magic, Manjit’s works create universality. Despite being a Sikh, his art is not confined to Sikh communal culture. He draws from all cultures, places them amidst nature, and threads them together with the thread that is not there.

This thread is not indicative of any culture; it is spun with wonder. The magician may belong to a particular culture, but the magic belongs to all. The wonderland of Manjit’s art is as enchanting for the audience as it was for Manjit himself.

Returning to my own experiences, Manjit’s paintings offer a subtle artistic hint of humour and wit, leaving viewers deeply affected by their pathos-driven humour. The tiger’s inability to eat bananas transforms it into a goat. This metamorphosis is possible only in art—particularly Manjit’s art.

The goat’s encounter with the pumpkin is akin to serving bananas to a tiger. I do not believe Manjit created these paintings with deliberate thought about the paradoxes they convey. Instead, his works stem from his nature. Manjit’s free-spirited personality is embodied in his paintings. His presence was never somber, burdensome, or oppressive; rather, it was as light and radiant as his ethereal forms—like a sudden, luminous burst of form.

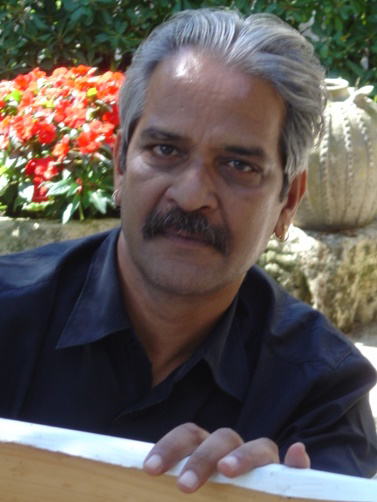

Feature Image: Manjeet Bawa| Courtesy: DAG

Born in 1956, is an artist, curator and writer. He has gained worldwide recognition and appreciation for his works through extensive participation in numerable exhibitions, shows, camps and other activities.