Among the many hats Ashok Vajpeyi wears besides being a poet, a columnist, critic and a cultural connoisseur, is running the foundation eminent artist Syed Haidar Raza left behind. Vajpeyi is credited as the moving force behind setting up of Bharat Bhavan in Bhopal, Mahatma Gandhi Hindi University in Wardha, Maharashtra and has also been the chairman of Lalit Kala Akademi (2008-2011). He turns 85 years old today, 16th January

In this freewheeling interview with Nidheesh Tyagi for Abir Pothi, Vajpeyi reflects on works of Raza Foundation, his long association with Raza himself and Swaminathan, his take on young and emerging artists and also about the current cultural scene in India. You can see here the full video of the interview.

Here we will start talking about the art stuff, and how the Raza Foundation is contributing to Indian Art as of now.

Well you know Raza sahab was very deeply concerned about remembering his old days of art struggle in Mumbai when he was a young artist and even in Paris later. So, he was deeply concerned about younger generations of artists.

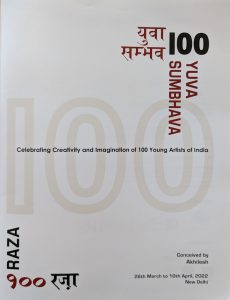

Not merely the visual arts but also poetry, music, and dance. Therefore, the basic mandate of the Raza Foundation as we created it is to provide help, promotion, and some kind of critical sustenance to the younger talent. So we do a series of activities which feature the young. Recently, for instance, we did a major show of 100 young artists in India in 5 galleries simultaneously in Delhi. It was the largest-ever show of young artists, well-curated, and curated by as many as five commissioners. We followed it with an exhibition of 20 young tribal artists from all over the country and sometime later this week we open in the India International Centre, the first-ever comprehensive exhibition of the Gond art largely featuring young tribal artists. So this is one part. Every year, we do a kind of colloquium of young, Hindi writers. To date, we have done about four to five sessions every year.

We have already featured about 200 young artists we picked up from all over the country along with young Hindi writers so there is a lot that we do by way of that. Then, we engaged a lot of young people to write biographies of eminent writers who are no more. We do a series called ‘Aarambh’ in which we invite young professional dancers and classical musicians and present them. We do a festival called ‘Uttaradhikar’ every year in which we ask the eminent gurus to recommend their young disciples and represent them as artists who are inheriting a great tradition. So there is a lot that keeps on happening. I may add that the other day Gulam Mohammad Sheikh publicly said that what Raza Foundation is doing singularly is what the three national academies are not able to do jointly.

One of the things is that Raza sahab when he was there, he contributed majorly to loads of emerging artists. The second thing is that he was also equally probably invested and engaging with people who were in music and literature.

Raza was a very unique personality, his hunger or thirst for knowing others was unfathomable. Anything that he had missed out on during his youth, he was very keen to take it inside of him, in a manner of speaking, retrospectively. So he used to meet young musicians, young dancers and of course poets. In fact, he was so deeply interested in Hindi poetry that one of my jobs, when I used to visit him twice a year, was to carry with me new books of poetry that might have appeared in Hindi. He was a person who was in essence both modern but also deeply Indian and an Indian who inherited the interdependence of the arts which was the normal phenomenon on the Indian scene until the end of the 19th century. It so happened that at the end of the 19th century that West-propelled modernism started and dance became classical and theatre and literature and visual arts became modern. So, a kind of divorce took place which we have not been able to undo despite many attempts.

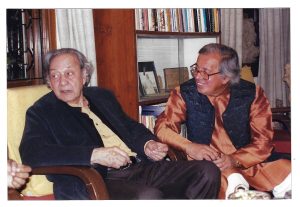

You had a very long engagement with him, you talked about going and meeting him twice or meeting him when he was here. How do you describe your association with Raza sahab?

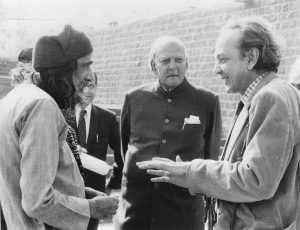

Well, my association with him was started by the fact that I invited him through the Govt. of Madhya Pradesh to honour him. He belonged to Madhya Pradesh and he held his first-ever show in his home state for the first time. We honoured him and we had a seminar on him and various publications. It was there that I published a small book of poems, my first book, and very reluctantly, I gave him a copy.

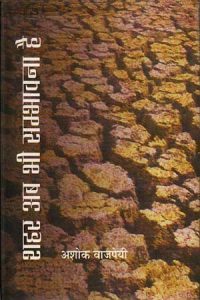

Shehar Ab Bhi Sambhavana Hai?

Yes, ‘Shehar Ab Bhi Sambhavana Hai’. And after about a year, I got a trunk call from him saying that he wanted to use one of the poems in one of his paintings. It is an iconic painting of 1981, largely known as ‘Maa’ but it has this line “Maa lautkar jab aunga, kya launga”, which is a line from one of the poems in that book. So, his interest in poetry and my vulnerability to arts, played a role and I realised that his modernism was not run-of-the-mill modernism. Modernism world over is known for dominance, disruption, location, violence etc. In the case of Raza, the modernism that he practised, and therefore, I call it alternative modernism, was a consonance of silence, peace, of togetherness, that is one. Two, Raza’s relationship with nature was unique, he thought nature is the real world. And that humans have been allowed by accidents of history or biology to inhabit it. He had a sense of deep reverence for nature and that is how he and his wife Janine Mongillat together searched for a place in the South of France on the French Riviera, called Gorbio where nature unviolated and undisturbed in its peaceful exuberance existed. In a manner of speaking, he used to say, I live here as if I live in Narsinghpur, Mandla, or Kakaiya, they are all here. Most modernisms the world over have been based on the divergence between man and nature. In the case of Raza, there is no divergence, in fact, there is a submergence of nature in the homo sapiens and the homo sapiens in nature. It was an alternative. Narmada was the river of his childhood, and he would never mention Narmada as Narmada, he would always say Narmada ji and if I sometimes by mistake said Narmada he would immediately correct me. So, here was a modernism which has an element of celebration, unlike other versions of Modernism. Modernism is not known to be celebratory, it is supposed to be disruptive and interrogative. But here was a modernism which is celebratory. So, he was a very different artist altogether.

Courtesy- Raza Foundation

And what we’re the exchanges you would have, what kind of conversations were you having with him?

We had conversations about all things, we talked about Ghalib, Kabir, Baudelaire, Polish poets, and Indian poetry. You see, then again Raza has more or less 100 canvases in which he has used lines of poetry or words of poetry in Devanagri. He has inscribed it. It used to take a lot of effort to make it, to write and see if the spellings were right and all that. It includes verses from Sanskrit and Upanishads, from Medieval poets like Kabir and Tulsidas and Ghalib and Mir and even me. He had a wide range of this and no other modern artist that I know of in the world has given the word such an autonomous existence on the canvas itself.

Yes, at the same time you know, I also don’t remember anybody who was so invested in Indianism of our aesthetics and traditions. And at the same time, he was a Muslim and when you see it today….

See, he was tri-religious and tri-lingual. Tri-religious in the sense that he was a Muslim and never left his faith. He incorporated Hindu concepts through metaphysics in his art and he was also very deeply interested in Christianity. When he came and finally spent his last years in Delhi, we had to locate a temple, a church and a masjid which he would visit every week. This was his tri-religiosity. He was trilingual, he wrote and spoke such wonderful Hindi.

It is amazing, it is as if like reading poems.

Yes, and secondly, French and thirdly, English. If somebody from Europe would ring him up, he would talk in English, to a Frenchman in French. But if anybody rang him up from India or an Indian rang him up from anywhere, he would talk to him or her in Hindi. He embodied a plurality in a certain sense in his daily life, in his art and in his vision.

You have also closely worked with Swaminathan sahab. He also has so much contribution through your founding based on Bharat Bhawan and later on. How was that?

Swaminathan was a very restless, irrepressible soul. But Swaminathan was deeply interrogative of the western dominance of both art and ideas. If you recall, he started as a Marxist, he was a member of the Congress Socialist Party and then he moved on to the Communist Party but then he left politics altogether and took entirely to art. But he did not leave his interrogative spirit. Once, we were discussing something, Swami suddenly said I want to make a museum of the western man and I said, what do you mean by that? He said the western man has museumised all non-western men. Now our turn has come, we should put the western man in the museum. Second thing was that he did not believe in history, he believed in the simultaneity of time. And therefore, he used to say and assert, that in art there is no progress. You cannot say that a body of work today is more advanced, in spite of the techniques and technology, than let us say, Ajanta or Khajuraho or miniatures. So, there is no progress in art. And he used to say, just like there is no progress in religion, you cannot say that today spiritual thought is more advanced than what is embodied in Gita or more advanced than what is embodied in Quran or in Bible.

something, Swami suddenly said I want to make a museum of the western man and I said, what do you mean by that? He said the western man has museumised all non-western men. Now our turn has come, we should put the western man in the museum. Second thing was that he did not believe in history, he believed in the simultaneity of time. And therefore, he used to say and assert, that in art there is no progress. You cannot say that a body of work today is more advanced, in spite of the techniques and technology, than let us say, Ajanta or Khajuraho or miniatures. So, there is no progress in art. And he used to say, just like there is no progress in religion, you cannot say that today spiritual thought is more advanced than what is embodied in Gita or more advanced than what is embodied in Quran or in Bible.

Courtesy- Wikipedia

The other thing was that he was not willing to accept the notion that tribals are those people who have been left behind by history. His notion was that they were as contemporary, as modern as any other, like the so-called urbanised masses. He would cite any number of examples to say that the tribals in their behaviour and conduct are more civilised, and more considerate to both nature and man than the urban lot. Therefore, through Bharat Bhawan, we tried to, under the influence of both Karanth and Swaminathan, redefine modernity: that modernity is not the exclusive domain of the urban and that modernity is equally shared by the non-urban, by the rural, and by the tribal.

So he created a museum which had both tribal and folk art, more than a thousand works collected at that time and urban art. So you had Jangarh Singh Shyam, Bhuri Bai and then you had Akbar, Raza and Hussain. Now, this had never happened institutionally before Bharat Bhawan. Sadly it did not happen after Bharat Bhawan either. Therefore, he gave equal respect and equal place to the folk and the tribal. We watched with amazement that sometimes when rural folk or tribal people came to Bharat Bhawan and they went around, they were not amazed by or intrigued or shocked by the abstract art. For them it was a natural thing, they keep on doing abstraction all the time, it was the culturally illiterate middle-class people who would say “yeh kya hai?”. This sort of question was never asked by the tribal or the folk. So they were more readily amenable to abstraction than the urban.

I remember you talking long back, sometime in Nagpur, in 1992, talking about this educational literacy and cultural literacy and how they are eating into each other.

You see what has happened is that our entire education system hangs in a cultural void. Schools are designed and function as temporary

Courtesy- Raza Foundation

jails. The gate is closed, uniforms and this and that. Everything is like a jail and hospital, regimented. Whereas some of the great experiments that took place were in Santiniketan where classes were held under a tree. Which was what was happening in India before. It doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t have a proper building and all that. But everything has been designed to make a regimented disciplined

mind. And I think a lot of what is happening in India today in terms of violence, crime rates going up, murders, rapes, and hate speeches are all products of an education system and mind you most of these people are educated. An education system which gives you no sense of what a cultured, civilized human being should be. In a sense, it cuts into everything then because there is a triennial uniformity always set in by market forces, consumerism: the same kind of drawing room, same kind of food, same kind of television programme, everything more or less the same. You become the same kind of animals, without having the real touch of the great civilization to which you belong.

Going back to Swaminathan, you and this tribal story. I think it was 35 years back from now. Now it has found its orbit and it is becoming a good body of work. And so many young tribal artists are coming and setting up the Raza Foundation, how do you see it? This is one of the original authentic contributions of this partnership you had with Swaminathan and Bharat Bhawan

You see Bharat Bhawan played a big role. What we were doing in visual arts, Karanth was also doing the same thing in theatre. So first-ever full-length plays in Bundelkhandi, in Malwi and in Chattisgarh were produced under Karanth. And what were these plays? Bertolt Brecht, Samuel Beckett. So the same principle was being followed that the dialects of Hindi, also are the most energetic, vital links with reality and therefore, Brecht and Becket all can be performed in these languages. The second part was that Swami found Jangrah Singh Shyam, a boy who was breaking stones on the road when he was going to visit Patangarh. Patangarh is a place where at one time a great anthropologist Verrier Elwin had lived. As you know Verrier Elwin was a married man, he would father some children and then leave. So Jangarh Singh Shyam took him to his village and Swami brought Jangarh Singh Shaym to Bharat Bhawan. There was new material which the tribals had never seen such as paper, colour, pen and pencil and Jangarh Singh Shyam belonged to a tribe which is Gond Pradhan. Among the Gonds, the Pradhans are genealogical singers so they sing the genealogy ki pehle kya tha, chronicling Gond history, and how the world was born. So he was a musical mind and remembered those stories, what happened, and this is the miracle which is a recorded miracle, it has never happened, that a musical memory got converted into visual memory and the visual art that is born, is the Gond Art, at least 80 artists now and most of them belong to merely two districts mainly Patangarh and some to Mandla. Now, this is where a strange new school of paintings started. My brother Udayan Vajpayee coined the term Jangarh Singh Kalam, there is a new kalam and if you look at the paintings they are done with dexterity, subtlety, complete control over colours, with a language which communicates their own visual language and vibrant and they are telling the same stories which they would have been singing, that were now converted into visual images. So this is a great phenomenon and this is one of the most lasting contributions of Bharat Bhawan under Swaminathan.

Shyam, a boy who was breaking stones on the road when he was going to visit Patangarh. Patangarh is a place where at one time a great anthropologist Verrier Elwin had lived. As you know Verrier Elwin was a married man, he would father some children and then leave. So Jangarh Singh Shyam took him to his village and Swami brought Jangarh Singh Shaym to Bharat Bhawan. There was new material which the tribals had never seen such as paper, colour, pen and pencil and Jangarh Singh Shyam belonged to a tribe which is Gond Pradhan. Among the Gonds, the Pradhans are genealogical singers so they sing the genealogy ki pehle kya tha, chronicling Gond history, and how the world was born. So he was a musical mind and remembered those stories, what happened, and this is the miracle which is a recorded miracle, it has never happened, that a musical memory got converted into visual memory and the visual art that is born, is the Gond Art, at least 80 artists now and most of them belong to merely two districts mainly Patangarh and some to Mandla. Now, this is where a strange new school of paintings started. My brother Udayan Vajpayee coined the term Jangarh Singh Kalam, there is a new kalam and if you look at the paintings they are done with dexterity, subtlety, complete control over colours, with a language which communicates their own visual language and vibrant and they are telling the same stories which they would have been singing, that were now converted into visual images. So this is a great phenomenon and this is one of the most lasting contributions of Bharat Bhawan under Swaminathan.

One of the outcomes, later on, I saw Bhajju Shyam’s London Jungle Book. He has gone to London and painted it like a

white man in a museum. He went and painted London like a Gond would see it. That is like an amazing full circle of that journey. Coming to Bharat Bhawan you know, why do you think India could not have such good replications or examples for creating such cultural centres?

You see in India, cultural institutions are nobody’s priority. The politicians, bureaucrats, the businessmen. All these categories have no concern for the establishment of such institutions, their sustenance, their professional inheritance is nobody’s business so we are suffering from that. At that time many states wanted to have Bharat Bhavan. Maharashtra wanted, UP wanted, Bihar wanted and their officials

visited. I remember one very senior bureaucrat Additional Chief Secretary from Bihar came and I asked him, “Sir you go around anonymously, see for yourself.”, and then on the last day he had a meeting and he said Ashok I am convinced that we cannot do this in Bihar. I asked why because Bihar has such a rich culture. But he said, “No no that is not the point, the point here is that this place is run so efficiently by such informality”. So I said, “What do you mean?” He said, “You are the Trustee’s secretary and you have secretary education also and you still don’t have a room in Bharat Bhavan to sit, you sit under the tree and dispose of the files there.” And then somebody came and said “Aapne kaha tha sarangi mela karna hai toh humne uska pata kiya hai”. Toh humne pucha, “Kitne log hai sarangi banane wale poore desh mein?” Toh bole, “Pachattar ka pata chala hai”. Toh humne kaha, “Theek hai sabko bula lo, karenge kab? Kitna kharch hoga?” Toh usne kaha ki, “3 lakh 3.5 lakh”. Toh humne kaha, “3-3.5 lakh toh theek hai.”

The Additional Chief Secretary said this cannot happen because there is such informality going on. The point was, this year completes 40 years. In the first 9-10 years, Bharat Bhavan was on international map and today it is not even on the regional map. Nobody bothers, Madhya Pradesh never had an institution of international repute or standing. It has none today because Bharat Bhavan has been allowed to lapse. So there you are, there is no professional inheritance, no respect for professionals, today look at the visual arts, the best museums are private.

Courtesy- Wikipedia

I also wanted you to kind of maybe take us on a journey of experiencing art because you have travelled globally, you have seen great works and met people. Are there any specific pieces of art which got your attention?

For me, the world as a whole owns so much art that it is difficult in a lifetime even if you are visiting art sites in museums, galleries, collections, and displays every single day of your life. You will not be able to exhaust the entire wealth there is. Secondly, all over the world, especially in the west there is a deep and abiding concern for art as an important institutional framework of civilisation which is not here. Even our great museums that were made by the British, such as the Indian museum in Calcutta, are in such bad shape. Third, is that what you see is that civil society, by and large, at least the Indian civil society, is so begotten, so narrow-minded, and so culturally illiterate that it takes no interest in art. Some elements of civil society do, they once in a while take initiative and create private institutions in art, music or dance. The public institutions have more or less collapsed. They are standing physically but their aesthetic wealth has become inaccessible because there is no outreach programme of any consequence. There is no attempt to rearrange, all museums keep on rearranging their displays, once everything is spread, it remains there, with nobody to think in a new way.

Is it something to do with the spirit of questioning, and ideas and that we are not encouraging that in society?

Yes, you see, art makes you ask questions and these questions are both philosophical, metaphysical, spiritual, intellectual and modern. What is beauty? How is beauty rated? Is beauty a given or beauty is an artefact? Why in our own tradition we had veebhats ras and raudra ras which are not exactly very beautiful emotions but they are there now so why these? And through them you start questioning the status quo, whatever is given to you, you start re-examining it, is this what I deserve or is there something that is being denied to me? All these questions will arise in you as soon as you are responding to art. These are the questions that art has always been asking, so a civil society which reduces art at best to decorative functions to something which is merely an appendage which doesn’t have substance, the notion that art has actually no substance no content, it is all form. All these notions are so deep-rooted and the education system has created these notions in a big way that you cannot expect a civil society which is commensurate with artistic initiatives, artistic imagination, and artistic innovations.

Being from Raza Foundation and talking about society as we have it today, how do you see the current and forthcoming future of visual arts in India?

I must say that visual arts luckily have liberated themselves from the clutches of public institutions. Today, Lalit Kala Akademi and other such institutions do not exist in the imagination of the artist. They are in the periphery because visual arts have been able to create a domain of their own–more importantly, a market. So artists are not bothered with things like who is the chairman of the LKA–only the mediocre and the third-raters and the untalented would veer towards such institutions.

No significant artist would bother. However, public institutions cannot be relieved of their duties towards the arts. But then, who is going to question them? Today the media has completely withdrawn from the arts, whether newspaper or electronic channels—

There is no such media–responsible good media, good journalism is not happening that way.

Yes. So, the danger that exists, despite the fact that there is a market and there is a possibility for artists and young people who are taking visual arts as a vocation–all this is very far. But there is a glaring lack of criticality. Now if all critical essays are commissioned by galleries, then obviously the critique will not criticize because they have been paid for. Artistic activity in modern times in absence of criticality is bound to become peripheral, bound to lose meaning and substance, and bound to remain shallow and superficial. So that danger remains. It is a situation of deep despair. But then, the only way you can survive as a human being is against all odds–keep on dreaming keep on hoping. As an old man, I have not given up hopes, and I have not given up dreams, although, in actual life, there is very little to base them on.