Aliya Usmani

“A Humument”: What is it?

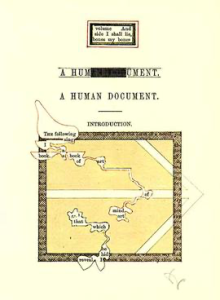

Tom Philips started working on something called the “A Humument” in the year of 1966 which is till date considered one of the most popularly known works of blackout poetry. The story goes that Tom Philips and R. B. Kitaj walked into a furniture shop and said “the first book I can find for threepence, I’ll work on for the rest of my life.” Eventually they found a novel by W.H. Mallock titled “A Human Document”.

Source: Wikipedia

Before even reading the book, he began treating it by painting or using techniques such as collage and cut up. As he was finished treating each page, he eventually published it as “A Humument” in 1970. The work has continued to draw attention till date for its contribution to blackout poetry.

There is a subgenre of poetry known as found poetry. There can be several types of found poetry. Found Poetry Review, a magazine that only publishes found poetry, lists four types of found poetry:

- Erasure: a poem that is created by erasing parts while the other parts are left behind

- Cento: when sentences from various poems are combined to form a single poem like a patchwork quilt

- Cut-up: this involves the actual physical cutting up of a text and then rearranging the physical pieces to form a new text

- Free-form excerpting and remixing: this involves taking an excerpt from a source text and rearranging to create something new.

However, as www.thehistoryofblackoutpoetry.org points out, there’s a fifth type that is often neglected. This is the infamous blackout poetry. The website further says, “Blackout poetry refers to any poem in which the author covers a majority of a source text in favor of leaving a handful of words exposed to form a poem. There are many ways to cover the preexisting text. Poets paint, collage, scribble with pen and pencil and crayon over pages of books and newspapers and all kinds of other texts. Even though there is variation in the how, they all do the same thing, which is obscure the source text but never remove it.”

The issue is that blackout poetry is often neglected as an independent category and is more often than not conflated with erasure poetry. The words in blackout poetry are always there, they are just hidden behind a sharpie.

Some blackout poets such as Tom Philips cover the source text using a pen or photographs, the point is that the original source text is not destroyed or damaged. Therefore, blackout poets always add something and never subtract from the source text. That addition is in terms of the meaning of the text but also in the way that it looks. Consequently, owing to these new aesthetics, new political meanings also emerge. For instance, the political connotation of erasure poetry is violence, as poet Solmaz Sharif states, “Erasure means obliteration. The Latin root of obliteration (ob- against and lit(t)era letter) means the striking out of text.” A text is harmed when parts of it are completely erased.

However, the connotation of blackout poetry is quite different, since it doesn’t violently erase or subtract from the text. Blackout poetry, in terms of its political connotation, is more closely related to censorship as the original remains and is not completely destroyed.

Placing Blackout Poetry in a Historical Context

It is quite difficult to identify the first ever blackout poem. Moreover, it is perhaps also a futile task to identify the very origin of any type of poem or a literary movement as one would hardly find any concrete answers. We might find certain predecessors or identify general trends but it is highly unlikely that we can find the very first.

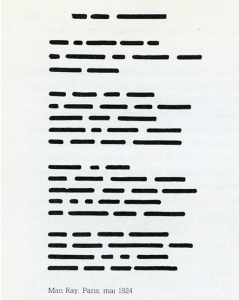

One work that has often been looked upon as the origin of blackout poetry is a piece from Man Ray that came out in 1924 in the Dada artists’ journal 1924. Even though there are scholars that don’t even consider this particular piece of poetry, it must be conceded that some of its attributes do qualify it as a blackout poem.

Source: Poets.org

Man Ray’s piece consists of black lines that are thick and both long and short. They are arranged in a poetry like format and have 17 lines that come together to form four stanzas. According to Michael Powell, it was Man Ray’s involvement with the Dadaist movement that led Man Ray to deconstruct the very nature of reading and writing.

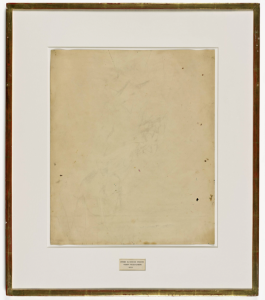

Any discussion on blackout poetry is incomplete without including Rober Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning drawing from 1953. In this drawing, Rauschenberg attempted to create a drawing out of using only an eraser. In order to create such a painting he approached painter Willem de Kooning to ask for his painting to be erased (Rauschenberg found erasing his own painting unsatisfactory). He ended up erasing de Kooning’s painting to such an extent that it came to look nothing like the original.

Source: SFMOMA

Art and literary movements often coincide and are inextricably linked. While it is obvious that what Rauschenberg created is a painting and not a poem. However, it is highly probable that Rauschenberg’s artwork influenced erasure poetry and therefore, in turn blackout poetry because both types of poetry were deeply interconnected in the beginning. Blackout poet Travis Macdonald has pointed out that both blackout and erasure poetry was “spurred in no small part by similar gestures in the visual arts.”

In the 1920’s, at a surrealist rally, Tristan Tzara created a poem by just pulling out random words from a hat using the cut up method. As per www.thehistoryofblackoutpoetry.org, this method was elaborated upon by the beat poet and painter Brion Gysin when “he placed newspapers on his table to keep it from being damaged as he cut papers atop it with a razor blade. As he cut, the newspapers became cut into pieces as well, and Gysin began rearranging them in new ways. He, Sinclair Belies, William Burroughs and Gregory Corso later went on to publish a book of these cut-up poems entitled Minutes to Go (1968). Gysin and Burroughs further published throughout the 60s and 70s.”

As the 1960’s rolled in blackout poetry slowly began to permeate in some parts of the world. In London, Tom Philips in 1967 started to use blackout poetry which has also been referred to as erasure due to the constant confusion about the two different categories. Tom Philips was not alone in it. In 1962, in Austria, Gerhard Ruhm used a newspaper as his source text to create one of the very initial blackout poem. He did so to comment on how the paper called Osterreichische Neue Tageszeitung did not merely report the news as it was but added to the news. To make his point Ruhm only left the word “und” or “and ” exposed while he hid all the other text on the front page of the newspaper for six days in a row.

In Italy another blackout poet popped up, he was Emily Isgro. He also produced his first blackout poem by blacking out lines in the newspaper while leaving only some words exposed. It is referred to as canellatura or cancellation. However, his source texts were not limited to newspapers but encompassed a wide variety of sources such as the Italian constitution, novels and encyclopaedias. His works are popular as having made an immense contribution to visual and conceptual poetry in Italy. His poetry consists of just thick dark lines but they do resemble blackout poetry that we see today. However, Isgro is hardly famous.

Doris Cotton, an American artist, in 1965 produced the “Found Word” series. Her work is truly mesmerising in terms of its subject matter and the source text. She has used her childhood dictionary’s pages as a source text and has covered it with masking tape and has painted and drawn over it. She felt that by doing this she was “making connections, not writing poetry.” However, others continue to look upon her as a poet who produces blackout poetry.

From Belgium, Marcel Brooddthaers also made his own unique contribution. He used the poem, “Un coup de dès jamais n’abolira le hasard” (1914) by Stéphane Mallarmé as his source text and used black stripes to cover its text, not a single word can be seen. Even though the work was not intended to be a blackout poem (it was an artistic experiment) it is seen as such.

All of these works laid a fertile ground for the emergence and consolidation of blackout poetry. Moreover, movements such as L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E and Oulipo further created the groundwork. Soon another community called Fluxus started producing more works.

Chris Piuma produced a book of erasure poetry called The Constellated Sonnets (1995), “a series of 150 poems in which Piuma erases all the words in each line except for one while maintaining all of Shakespeare’s original punctuation. According to his blog, he selected the words at random by “Rolling a d10; if a six came up, using the sixth word, and if there was no sixth word in that line, rerolling.””

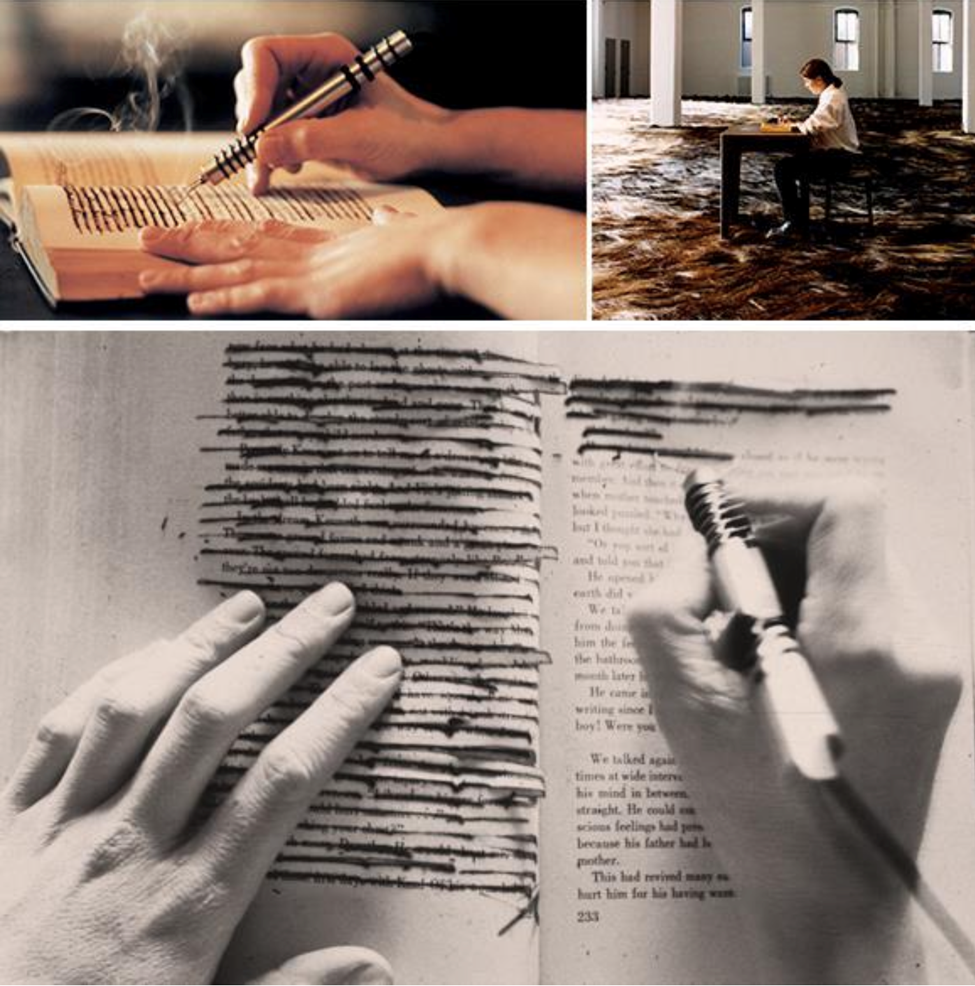

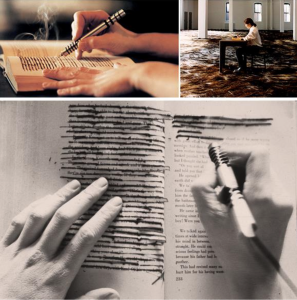

Essential to our discussion is the contribution of Ann Hamilton. Her work too was marked by creating art pieces that looked like blackout poetry but in reality consisted of no words at all. In her 1993 installation at the Dia Center for the Arts in New York she created her works right in front of the visitors. This included burning each line of the poem as it was simultaneously burned. The source texts that dealt with primarily consisted of books that did not have chapter headings. She chose these books on the basis of how the paper felt. Even though her work is not actually poetry per se but aesthetically resembles contemporary blackout poetry in more ways than one. Another artist called David Diao based in New York tried to incorporate blackout poetry techniques in his paintings. He used pages of art magazines that mentioned his work and silk screened them on his paintings. He then crossed out the name of the original author and wrote his name in its place. Diao and Hamilton’s work reflect an intermingling of art and poetry.

Fast forwarding to 2006, Mary Ruefle’s work titled ‘A Little White Shadow’ came out as a blackout poetry project. The work used Emily Malbone Morgan’s 1889 novel also titled ‘A Little White Shadow’. Many of the words were covered using white paint, but the words were not completely removed but only obscured and stayed on the page. ‘The Desert’ is a blackout poem published by Bervin that uses John Van Dyke’s work ‘The Desert’ as the source text. Instead of painting over the words she has stitched over them using a pale blue thread.

Source: Wave Books

As the 2000s came to an end, blackout poetry slowly began to take shape as an individual category. Scholars began writing about it and tried to make sense of how it is different from other types of poetry. Blackout poets began to receive much more attention from media, newspapers, and particularly from social media.

DIYing Blackout Poetry: the readers take over

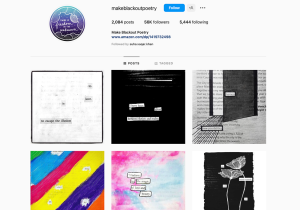

Most people today and especially post 2010 have come to know blackout poetry and everything that it entails. The popularity of this form of poetry at this point in time is not limited to creative writing programs or English literature classrooms. It has now permeated into the hands of the public and is no longer practiced only by a select group of people. Now the readers produce their own blackout poetry. An Instagram account @makeblackoutpoetry accepts submission from numerous DIY blackout poets across the globe and publishes them on their account.

Source: Instagram

Carrie Mallon, a tarot card reader has even published a how-to guide for creating blackout poetry. You can take a look at it here. According to www.thehistoryofblackoutpoetry.org, “the hashtag “#blackoutpoetry” have been viewed over 700,000 times as of mid April 2020 and there are over 147,000 posts labeled with the same hashtag on Instagram. The DIY shift in the blackout poetry community has been primarily driven by an increase in the use of social media sites like Twitter, Instagram, and Tik Tok.” These platforms also serve as a great platform because of their reliance on visual content. Perhaps, it is in the visual element that the popularity of blackout poetry lies.