Aditya Sisodia

The exhibition titled “Mapped!” held at the Asiatic Society of Mumbai shed light on the historical methods of mapping, particularly the Great Trigonometrical Survey of India (GTS) conducted during the British colonial period.

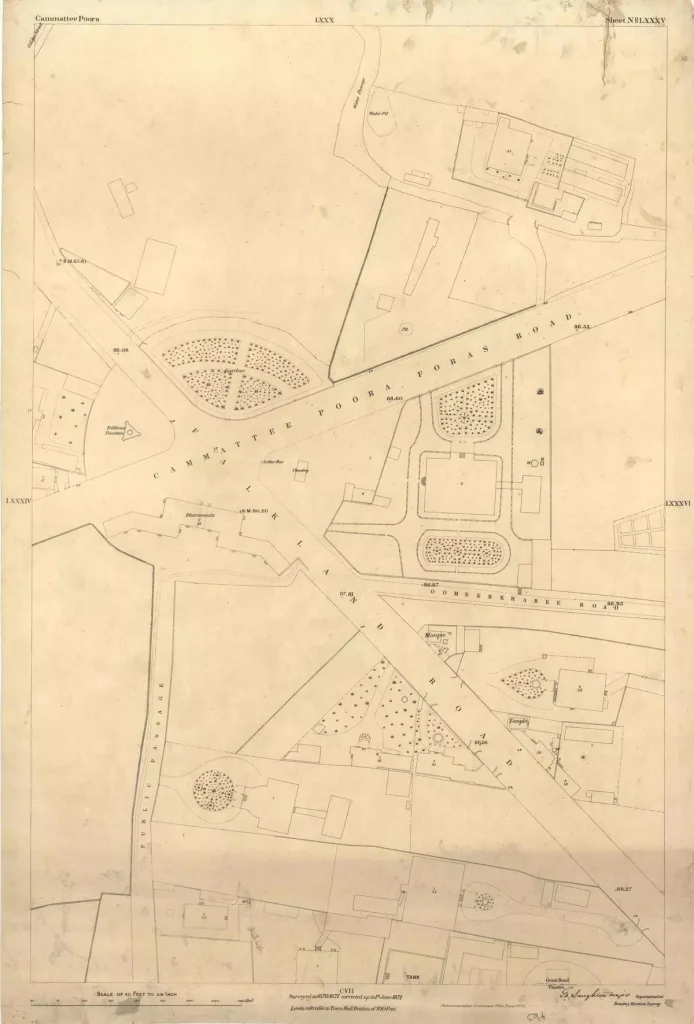

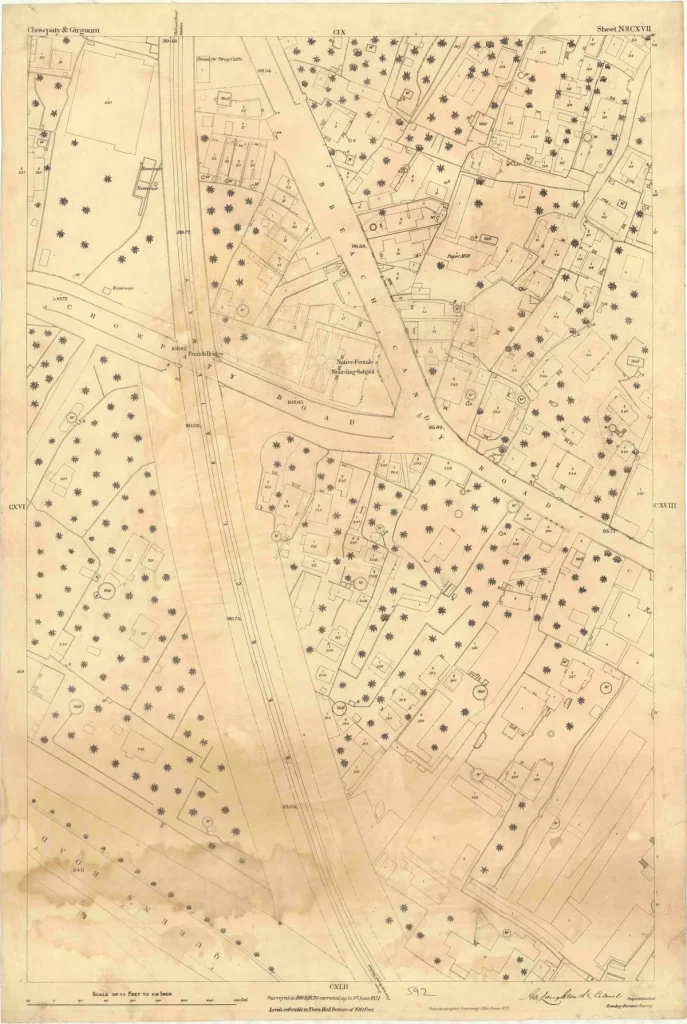

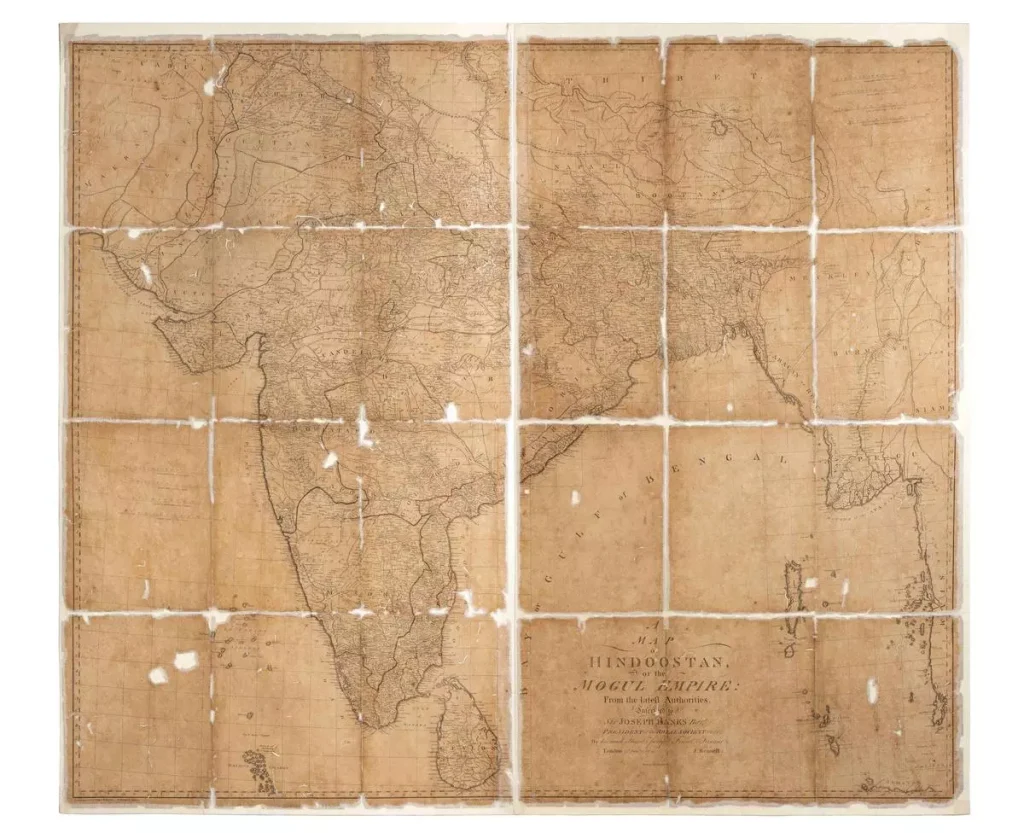

The exhibition, organised in partnership with the Rotary Club of Bombay, curated by heritage management firm PastPerfect, and supported by the Tata Group, focused on British dominions of the 19th century. It began with an 18th-century map of the Mughal empire by James Rennell, setting the context for the exhibition. Approximately half of the exhibition was dedicated to the GTS, while the rest showcased late 19th-century hyperlocal maps of areas in Bombay (now Mumbai) such as Chowpatty, Girgaon, and Kamathipura, created for the Revenue Survey.

Triangulation surveys, the most precise method of measuring terrain in the previous centuries, formed the basis of the GTS. The principle was simple: by calculating the length of a triangle’s sides based on the length of the base and the angles between the sides, a network of triangles covering a large area could be established. The GTS, initiated in Madras in 1802 by William Lambton and later continued by George Everest and Andrew Waugh, aimed to survey the entire subcontinent. However, the task turned out to be far more challenging than anticipated, leading to a delay of over 50 years in completing the survey.

Although the GTS employed theodolites, precision instruments for measuring horizontal and vertical angles, finding suitable vantage points for long-distance visibility was a daunting task. In some regions, such as present-day Tamil Nadu, temple gopurams (towers) were used as markers, leading to the inadvertent damage of the Brihadeeswara temple during the survey. The difficulties multiplied in dense forests, mangroves, and flat plains, where tracts of forest were cleared, and settlements were sometimes demolished to facilitate the survey. These actions, as mentioned in the exhibition notes, contributed to tension among communities and played a small role in the disaffection that culminated in the revolt of 1857.

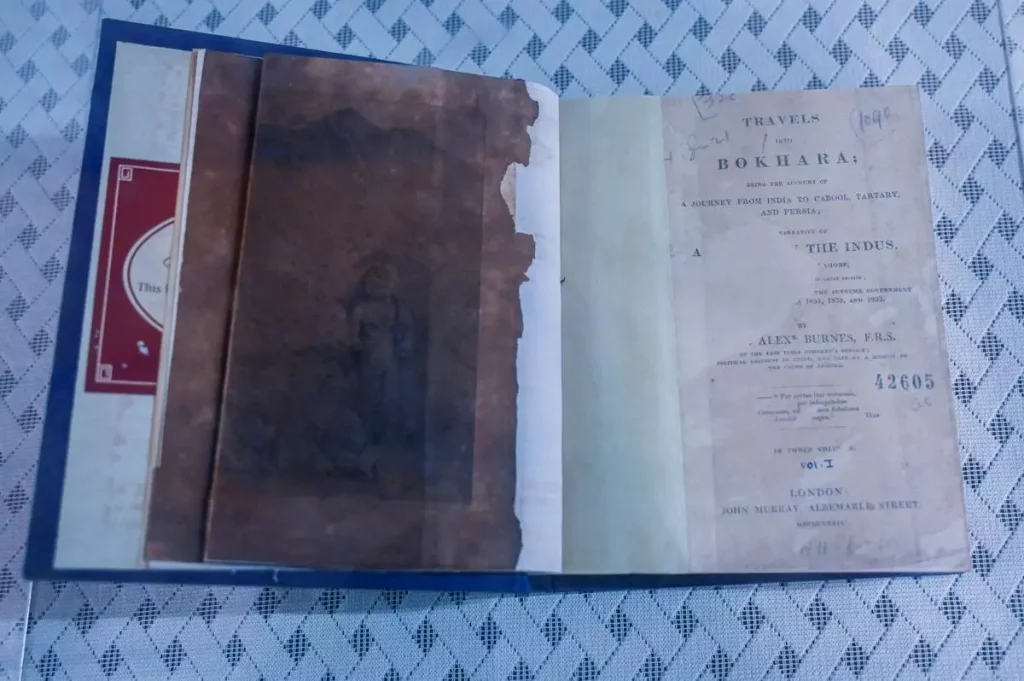

The British interest in surveying Tibet, despite its inaccessibility, stemmed from a fear of Russian influence in the region. The rivalry between the British and Russian empires during the 19th century, known as the Great Game, prompted the British to undertake surveys in Tibet and Afghanistan to prevent a potential attack on India. Unable to access Tibet directly, the British administration leveraged trade and pilgrimage routes between Tibet and the Kumaon region in present-day Uttarakhand to train surveyor-spies known as Pundits. Equipped with basic instruments concealed in walking sticks, such as thermometers to measure altitude and their own two feet to measure distance, the Pundits contributed valuable data to the surveys. Notable figures like Nain Singh, who traveled to Lhasa and surveyed the Sutlej River, and Abdul Hamid, who took the route through the Karakorum range from Leh to Yarkand in Xinjiang, achieved remarkable accuracy in their measurements over thousands of Kilometers.

While the exhibition “Mapped!” provided a glimpse into the extraordinary efforts and challenges faced by the surveyors of the GTS and the Pundits during the British colonial period in India. The exhibition also touched upon the geopolitical context of the era, particularly the Great Game, a strategic rivalry between the British and Russian empires. This rivalry, driven by fears of Russian expansionism, influenced the British interest in mapping regions like Tibet and Afghanistan.

The British administration, recognising the importance of Tibet in the Great Game, found innovative ways to bypass the restrictions on foreigners entering the region. They capitalised on the existing trade and pilgrimage connections between Tibet and the Kumaon region, allowing them to train surveyor-spies known as Pundits. These Pundits, lacking sophisticated instruments like theodolites, relied on basic tools and their observational skills to gather vital information.

Notable among the Pundits was Nain Singh, who made two daring journeys to Lhasa and surveyed the Sutlej River. Abdul Hamid’s expedition took him through the treacherous Karakorum range from Leh to Yarkand in Xinjiang. These Pundits, through their remarkable accuracy and meticulous observations, contributed significantly to the mapping of these challenging and remote regions.

The historical context of the Great Game and the British interest in Tibet shed light on the complexities of geopolitical rivalries and their impact on mapping and cartography. The exhibition also hinted at the consequences of these rivalries, such as the massacre ordered by Colonel Francis Young husband during the invasion disguised as a trade mission to Tibet in 1904. The aftermath of this invasion and subsequent events, including the signing of the Simla Convention in 1914 to demarcate the India-Tibet border, further underscored the intricate and ongoing territorial disputes in the region.

“Mapped!” provided a comprehensive view of the historical mapping methods employed during the British colonial period in India. From the ambitious and laborious efforts of the Great Trigonometrical Survey to the daring exploits of the Pundits, the exhibition highlighted the immense challenges faced by surveyors and their contributions to the development of accurate maps. It also emphasised the intricate relationship between mapping, politics, and colonial agendas, revealing how mapping was not just a technical exercise but a means to assert control, expand influence, and navigate the complex power dynamics of the time.

By exploring the exhibition and delving into the historical narratives of mapping in colonial India, visitors gained a deeper understanding of the complexities and nuances associated with the creation of accurate maps. The exhibition underscored the significance of mapping not only as a scientific endeavour but also as a tool for exerting control, shaping narratives, and understanding the world in a broader geopolitical context.