American sculptor Ruth Asawa was well-known for her elaborate wire sculptures, public commissions, and commitment to art education. Asawa, born in Norwalk, California, in 1926, had a career spanning multiple decades and was involved in various artistic activities. Asawa’s creative career started while she and her family were detained during World War II, first at the Tule Lake War Relocation Centre in California and then at the Rohwer War Relocation Centre in Arkansas. She studied sketching from another internee and found inspiration and comfort in art despite the difficulties of being confined.

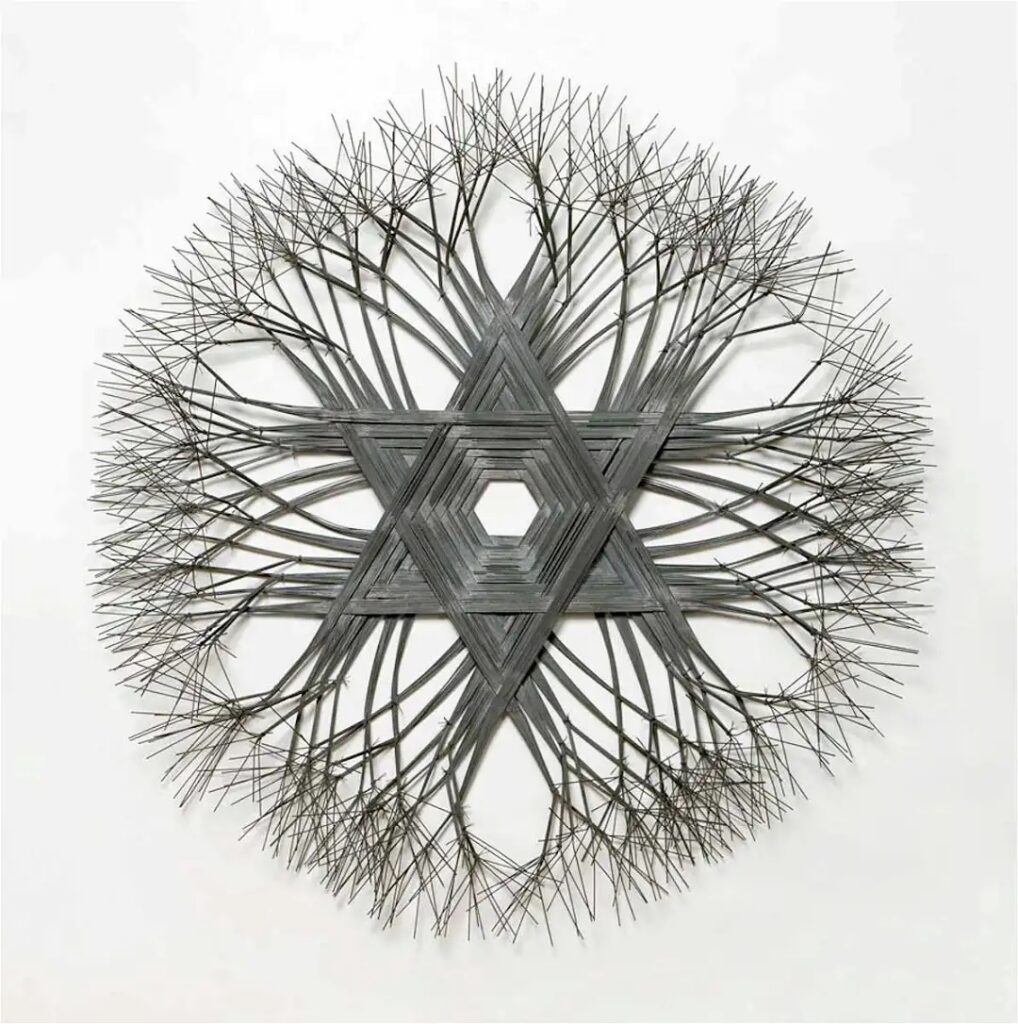

Following the war, At Black Mountain College in North Carolina, Asawa studied under renowned artists, including Buckminster Fuller and Josef Albers. She started working with wire as a medium for sculpting, eventually developing her hallmark style, which consists of intricately woven objects.

Asawa frequently addressed nature, geometry, and the interconnection of shapes in his wire sculptures. Her drawings and sculptures merged to create delicate yet intricate works that prompted spectators to consider form, space, and light. Along with her artistic endeavours, Asawa firmly commits to campaigning and arts education. She strongly supported arts education in public schools and was instrumental in founding the San Francisco School of the Arts.

Asawa has won various honours for her contributions to the arts; in 2018, the Whitney Museum of American Art hosted a retrospective of her work. Her legacy as an artist and a supporter of arts education is still powerful, and her work inspires audiences and artists around the globe.

Personal life of Ruth Asawa

Ruth Asawa stayed home to raise their six children after marrying Albert Lanier in 19492 at 23.3. Asawa was considered a “properly domestic” wife and mother since she took on a parental role at a young age. That her audience felt she should be naturally inclined to create “feminine” art, influenced by “female” craftwork and art forms that women had traditionally produced after finishing household tasks, may not come as a surprise. When she first started making wire sculptures, these were the descriptions given to them.

Asawa and her six siblings were forced to assist their parents with farm work as they were born into a family of impoverished Japanese immigrants. After the day, Asawa remembers travelling home on the back of a waggon and dragging her feet on the ground to entertain her six-year-old imagination with flowing patterns. When she started studying under architect and theorist Buckminster Fuller at Black Mountain College, she would recall these shapes. In addition to popularising the geodesic sphere, Fuller experimented with housing and other projects that used lightweight, contractible materials that used their assembly geometry to generate sturdy, well-built structures.

While studying under him, Asawa investigated topics like ambiguous positive and negative space and constructed larger objects out of smaller ones. Asawa was introduced to Mexican basket weaving on a forty-dollar vacation to Mexico that she could hardly afford. The impressions she had imprinted in the dirt as a youngster were eventually brought to life in the organic forms of her wire sculptures, thanks to the weaving skills she learnt on this trip. Her notoriety began with these pieces.

Asawa and other Japanese-Americans who were forced into internment camps during World War II have a complex sense of who they are as Japanese-Americans. Optimistically, Asawa listed only the benefits of her incarceration, such as having time to develop her artistic abilities and drawing inspiration from Disney animators in detention. However, it was her “Japanese-ness” that condemned her to that fate; it’s possible that the persecution she experienced led to her rejection of an ethnic identity. We should view Asawa’s self-description as American, rather than Japanese or Japanese-American, as a more representative “label.”

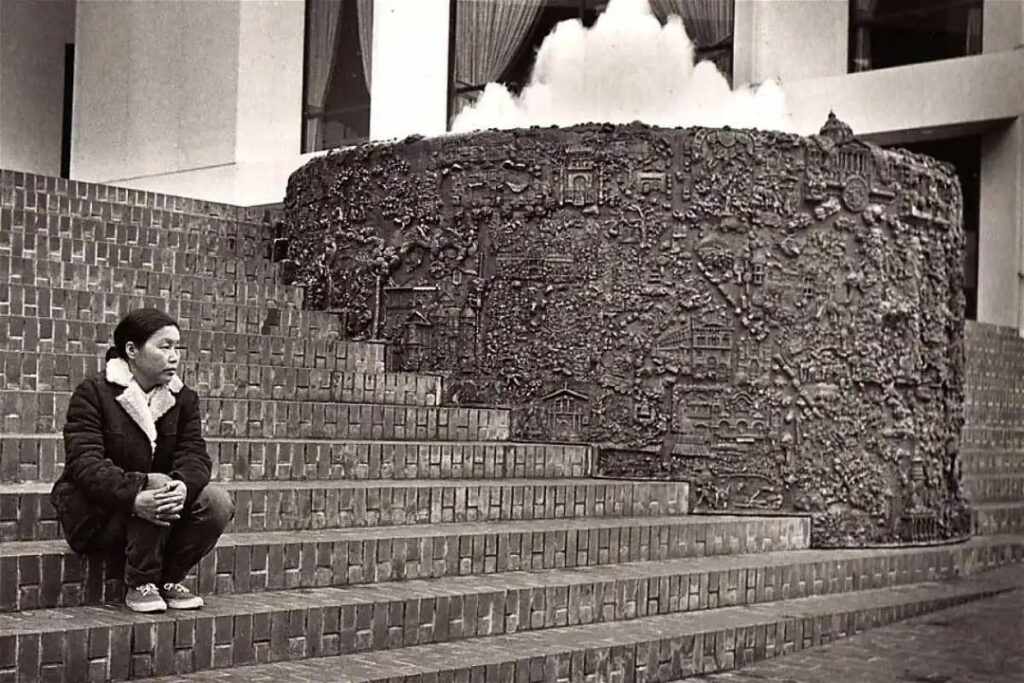

Ruth Asawa Fountain

Ghirardelli Square in San Francisco has a stunning public fountain called the Ruth Asawa Fountain. The fountain, created by well-known sculptor Ruth Asawa and placed in 1968, has become a cherished landmark in the community. The fountain’s captivating water cascade is produced by several cylinders with concentric wire mesh hanging from a central frame. Asawa’s usage of wire mesh reflects her unique style, which frequently blends geometric and natural elements with detailed wire sculpting.

Beautifully crafted, the Ruth Asawa Fountain is a meeting spot for locals and tourists. Its placement in Ghirardelli Square, a well-liked dining and retail area, makes it easily accessible to many. Asawa’s fountain is evidence of her sculptor skill and commitment to producing community-enriching public art. It pays homage to her legacy and fills onlookers with admiration and wonder.

Given the abstract nature of her work, Asawa’s near-refusal to identify as a woman or Japanese in conversations about herself as an artist mostly had no effect. But when her most contentious piece, Andrea, a fountain in San Francisco’s Ghirardelli Square, first appeared, questions of race—especially femininity—became highly public.

Asawa said on the fountain: “As you look at the sculpture, you include rather than block out the ocean view which was saved for all of us, and you wonder what lies below the surface.” Asawa’s fountain not only conspicuously eschews the modern feminist goal, but by implying that the mermaids are lesbian couples with their offspring, it can also be seen as supporting LGBT rights.

Her art bears the influences of Buckminster Fuller and Josef Albers. Assume her works can only be a part of one art trend. In that case, her work with baker’s clay and her brilliant use of the crochet e-loop in her wire sculptures make her most closely related to the Craft Studio movement. When Asawa’s false labels of “Japanese,” “Japanese American,” “feminine,” and “feminist” are removed, her true identity as an American artist who sculpts using wire and casts fountains from baker’s clay models can be seen.

Through her accomplishments, she pushed for the recognition of women and Japanese-Americans. Yet, it would be incorrect to map these identification designations onto the subjects she addressed in her artwork. The more we realise how society tends to “other” minority groups, the more we will be able to resist the need to categorise them. Because of her uniqueness and nonconformity, Asawa has contributed to the instillation of a society that questions white and male superiority. Considering her development, we may classify her as a pioneer in art and career.

Ruth Asawa Reappraised

‘During her later career, she found the demands of a full-time gallery relationship too demanding and participated less and less in contemporary art exhibitions. So, rather than simple obscurity, what Asawa may have had by the end of her life instead was the wrong kind of renown, at least in the view of contemporary art circles (then, as now). The 2013 catalogue Ruth Asawa: Objects and Apparitions that accompanied the sale of some of her wire sculptures at Christie’s positions Asawa as a sculptor whose aesthetic could be misunderstood owing to its visual and technical similarity to traditional handicraft. What the catalogue leaves out, however, is more telling: while the essays address the issue of her gender and the “craft question” head-on, they sidestep her public work and teaching career almost entirely. This suggests that, at least in the case of Asawa, there is a more complex reason for her on-off relationship with the marketplace than her use of craft techniques and materials and that the now-familiar narrative of the “overlooked craft artist” is too reductive an account for the reception of her oeuvre. A shift in the perception of her practice and identity as an artist may account for her recent success on the secondary market for postwar sculpture, where she is now, posthumously, a rising star, writes Sarah Archer.

During her lifetime, Asawa’s reception was influenced by two main issues. First, her early typecasting as a craftsperson whose artistic objectives were submerged by a meditative and repetitive working manner resulted from the intersection of her formal style and gender. Second, Asawa shifted from making individual pieces for gallery and museum exhibitions to creating public art. His work aligned with an aesthetic viewpoint that the people adored and understood, but it was distinctly out of sync with modern sculpture. Her realistic, even emotive fountains are two of her most well-known public works; they are the idea and artistic opposite of her hanging sculptures in the wire.

Ruth Asawa left behind a significant and enduring impact as an artist and supporter of arts education. She paved the way for spectators to ponder the beauty of form, space, and light by creating elaborate wire sculptures that blurred the lines between drawing and sculpture. Her delicate and intricately structured compositions, frequently influenced by geometry and nature, demonstrate her technical mastery and acute artistic vision.

Beyond her creative accomplishments, Asawa fervently supported arts education, seeing its potential to improve lives and inspire creativity in people of all ages. Her belief in the transformational power of the arts was demonstrated by her efforts to build the San Francisco School of the Arts and to advocate for arts instruction in public schools.