Artists who Captured Durga Puja of Bengal

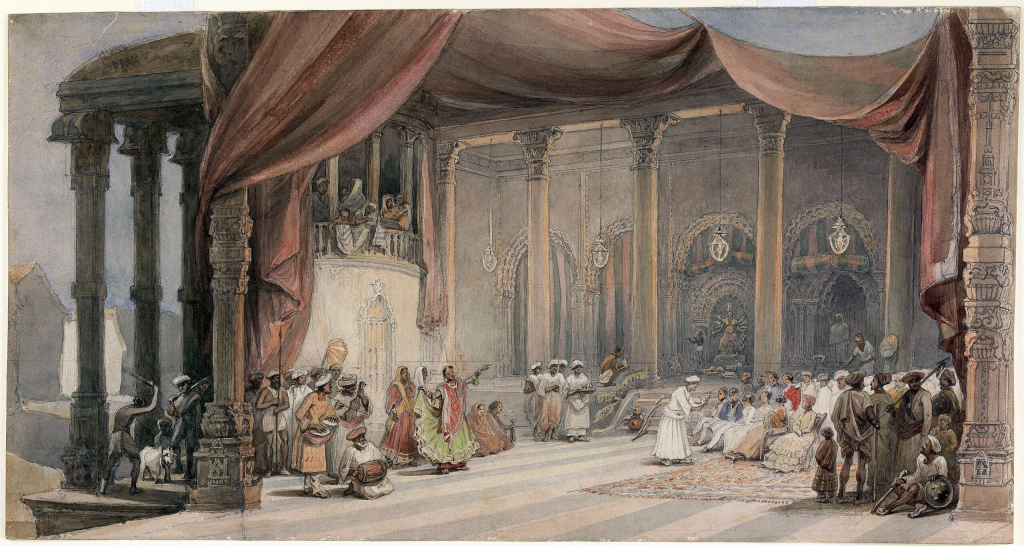

Worshipped through Durga Puja, one of the grandest festivals in India, which commemorates the victory of Good over Evil as goddess Durga defeats Mahishasura demon. There is more to this festive season than just worship; it provides a platform for artistic blooms: sketches, drawings, paints and artwork bringing the essence of Durga Puja alive.

Durga Puja Drawings

Durga Puja inspires a plethora of drawings, from intricate sketches to vibrant oil pastel creations. Artists worldwide draw inspiration from the divine aura of the festival, crafting detailed Durga Puja scenes and intricate depictions of the goddess herself. These drawings serve as a visual ode to the festival’s grandeur.

Durga Puja Festive Artworks

But the festival is more than just drawings: artists work in a range of mediums. Brush strokes in words, painted on canvas where the power and grace of every single one of those beautiful canvases restored faith on Goddess Durga decorates each frame and fills us with her immense presence as Soma protrays beauty beyond photo-editing. The artworks depict the colours and celebrations of the festival come to life.

1. Nandalal Bose

Nandalal Bose, a luminary in the Indian art world, left an indelible mark with his unique style of painting. His masterpieces, often inspired by Indian mythology and culture, include depictions of Durga Puja. Bose’s artistic prowess illuminated the festival, infusing it with reverence and artistry.

.jpg?mode=max)

Radha Charan Bagchi

The Durga Puja becomes more artistic with the presence of an artist like Radha Charan Bagchi. His works resonate with the festival’s spiritual importance, representing an equal pursuit of devotion and creativity. Bagchi’s art keeps reminding us and evokes the same nostalgia of this festival we all love.

Courtesy – Tumblr

Bikash Bhattacharjee

Bikash Bhattacharjee, renowned for his evocative paintings, embarked on a Durga series that encapsulates the goddess’s divine aura. His artworks portray Durga with a unique perspective, capturing her essence in ways that leave a lasting impact on the viewer’s soul.

Gaganendranath Tagore

Gaganendranath Tagore was a pioneer of modern Indian art, pushing boundaries by experimenting with various forms—from caricatures to Cubism. His artistic journey brought a fresh perspective to Durga Puja, introducing innovative and abstract interpretations of the festival’s underlying themes, marking a unique fusion of tradition and modernity never seen before.

Courtesy: Google Arts & Culture

Conclusion

Durga Puja transcends religious boundaries with art, culture and spirituality woven into a beautiful fabric of life. While the magnificent and intricate depictions of the divine form reflect the grace, exuberance and beauty of Durga Puja on a grand canvas, artists use every possible material in existence to pay homage, through creative expressions. Artists like Nandalal Bose, Radha Charan Bhagchi, Bikash bagchi and Gaganendranath Tagore are some of the names that stand out in the artistic legacy of this festival. Durga Puja is not just a festival of venerating the goddess, but is in all truth an ode to art, as we pray to her, we celebrate her through the hands that arouse divinity with creativity.

Lion as a Motif Across Civilisations

As Navratras are around the corner, a time of celebration and spiritual reverence, the image of Goddess Durga riding her lion begins to take centre stage in homes and temples across India. A symbol of divinity and victory, this inspirational motif is as iconic in the sacred arts and culture of the region. However, the lion as Durga’s vahana( mount) represents braveness, strength and capabilities to fight evil. Lions have denoted eminence since time immemorial in numerous forms, from religious iconography to broad cultural representation as a symbol of authority, safeguarding prowess, and royal authority. In this text we will delve onto the subject of how the lion became a through-line in art making, from ancient carvings to medieval paintings and annotated forms. By placing a unique emphasis on the Durga connection, we hope to unmask the perseverance of this king of animals in art traditions and its lofty position during the revered days of Navratra.

1. Ancient Art:

Mesopotamian: Lions, which were a common motif in ancient Mesopotamian reliefs, represent the figure of royalty that all but subdue chaos.

Lioness goddess Sekhmet (Egyptian): War and healing. The most common symbol of Pharaohs is lions since they showed might.

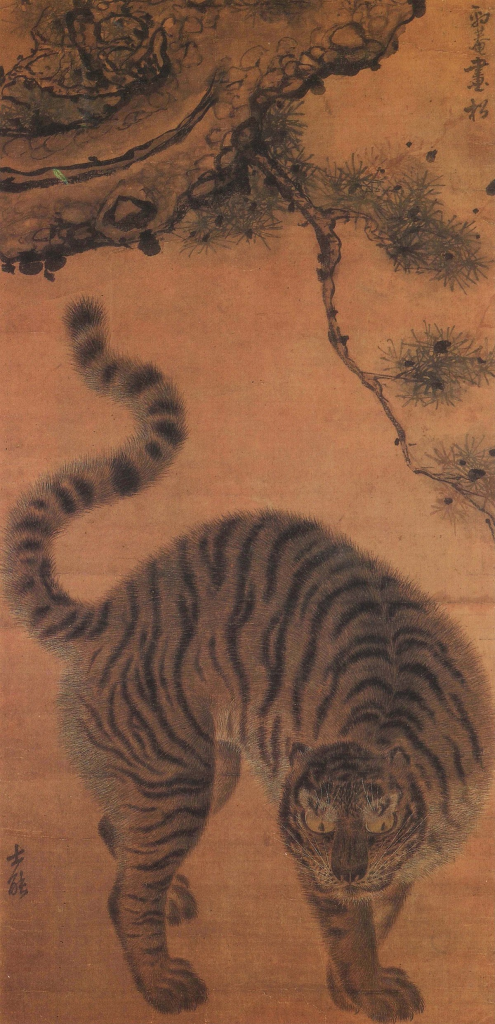

In China: In Chinese art, tigers mean protection and power. The forms that emerged was those of warrior with banners, guardian images in tombs.

2. Religious Symbolism:

Buddhism- The Lion’s Roar of the Buddha Dharma symbolizes spiritual strength. In Buddhist temple architecture, a lion is similarly regarded as a guardian.

Hinduism: The goddess Durga rides the lion, indicating her strength and protective nature. The tiger is also associated with Shiva, who hold a tiger skin suggesting he has defeated nature.

3. Medieval and Renaissance Art:

True English Heraldry: Lions were a common feature in armorial bearings as the ultimate symbol of strength and valour.

Medieval manuscripts: Lions appeared in biblical stories, such as Daniel in the lions’ den, where they symbolized both danger and divine protection. In this context, lions were often depicted as fierce but subdued by God’s power, illustrating themes of faith and salvation.

4. Asian Art:

Indian Miniatures: Mughal tigers and lions, Indian Miniature — tigers and lions frequently appear in mughal art as part of royal hunting scenes or nature depictions.

Japanese Art: Tigers are fierce animals showing courage and leadership which is the ideal representation of Japanese Art found in Nihonga paintings or traditional screens.

5. Modern Art:

Be it Symbolism or Surrealism: Artists such as Salvador Dalí utilised tigers and lions alike to symbolise subconscious fears and depravity, for instance perhaps best typified by his ‘Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee’ painting!

A popular trend in modern pop art have been images of lions and tigers, often rendered in bright colours as a representation of strength or the wild within the framework of consumerism.Their existence in art cements their status as physical and metaphorical figures, acting as protectors or predators as well divine or princely personalities.

Navratri history and significance

Navratri is Sanskrit for “nine nights,” a Hindu festival that honours the victory of good over evil and the divine female force, or Shakti, which is personified in the goddess Durga. All over the country of India it is celebrated on a massive scale, Hindus across the world too do observe Navratri however there are differences from region to region in terms of origin and customs. While Navratri is a religious festival, it holds cultural, social and artistic values as well. Based in the ancient Hindu mythology, the festival has changed over millennia under the influence of local practices, royal patronage and Vaishnavism philosophy.

Mythological Origins of Navratri

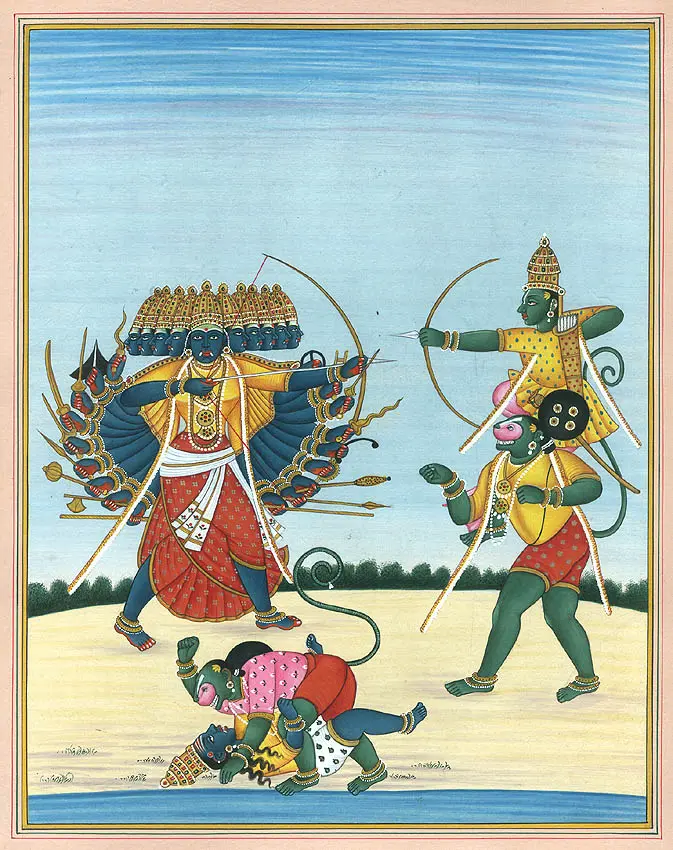

The mythology of Navratri is a fascinating one, full of legends and stories defining the essence. One of the most popular legends is that of battle between the goddess Durga and the demon king Mahishasura. Hindu Mythology describes Mahishasura as a very powerful demon who was given a boon by Lord Brahma that made him almost invincible, on the condition that he can be killed only by any women. Fuelled further by the belief in his own immortality, Mahishasura ran rampage across heaven and earth. With the gods incapable of stopping him, they called upon Durga–a ferocious form of Shakti. On the tenth day, Durga killed Mahishasura herself and saved the world from a great terror. The power of good over bad and the victory of feminine divine is represented in this win, so mother Durga is the central figure of Navratri.

Another major Navratri myth is that from the Ramayana. It is said that the nine days were when Lord Rama worshipped Goddess Durga to seek her blessings before going on to fight Ravana, the demon king. Rama had defeated Ravana on the tenth day by that Mrakshika-Mukha nagara-dahan (burning an entire Lanka inside a single flame) to be exact, and it became a victory over evil, hence Vijayadashami or Dussehra. In this one, Navratri is the festival celebrating Rama’s devotion and righteous struggle against the demon king Ravana; propelled by fierce grace of Durga Maa – making it perfectly align with Dussehra celebrations majorly done in northern part of India.

Historical Development of Navratri

Although early Vedic references to Navratri are scarce, it has prehistoric roots. However, it seems that the roots of Navratri lie in a much older concept during the Vedic period — Shakti worship. The worship of Durga and other goddesses was slowly formalised over time, particularly in the medieval period when shakti cults emerged as significant social formations. The festival as we know it today is a sum of centuries-old devotional practices and rituals that adapted with the changes in society.

During the medieval era, Navratri achieved widespread significance with royal families playing a key role in propelling and enlargement of grandness to it. The festival loses its ownership of Durga Puja being Bengal where it became festive during the time around the Mughal Empire. This have been organised privately since the time of Maharanas and the first major one being debt by a Bengali Zamindar (landovers) or Royalty where Brahmins are invited for grand celebrations with Durga Puja in which it became religious-cultural festivity for community to gather together. The folk dance traditions of Garba and Dandiya have been popularised in the state of Gujarat, where this festival is celebrated with militants, and these ritual forms now remain indelibly associated with Navratri. These dances are dedicated to the Goddess — symbol of life, community and of course, the triumph of good over evil.

Even during the colonial era, where the British imposed upon us their own times customs and values, Navratri remained a testament of Indianness and spiritual resilience. The festival came to be an opportunity to express cultural pride, particularly in states such as West Bengal where Durga Puja was also transformed into a nationalist event, encouraging and supporting local traditions and insulate resistance from colonial influence.

Regional Variations in Celebrations

While all over India Navratri is celebrated widely, its rituals, customs and importance vary from region to region. The theme of the triumph of Durga over evil is common to all, but practices and rituals around Navratri are influenced by local cultures and histories.

So in case of East India (Durga Puja WestBengal, Assam and Odisha: A five day Navratri are synonymous with”Durga pujaparva”. The final five days of the festival reverberate with a heightened energy — statues of Durga crafted in elaborate detail are worshipped and carried in grand public processions. Bengal put up the grandest of art, music and dance for Durga Puja which was not just a religious but equally a cultural extravaganza. The festival ends with the immersion of Durga idols into water (such as a river), which signify the departure of Goddess Durga to her divine abode.

Western India (Garba and Dandiya): Navratri is a major festival in the Gujarati and Marathi community, where they perform Garba, or dance of clapping with joy along with Dandiya. These concentric circles symbolise the circular and eternal time. The dances are performed around a lamp or image of the goddess by men from rural, with them all clad in colourful traditional attire. Garba and Dandiya Raas done during the festival manifests the vibrancy of socialisation & enjoyment of Navratri.

Southern India (Golu and Saraswati Puja) : In southern states like Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh Navratri is performed by arranging Golu — a setup of dolls and figurines depicting mythological characters/scenes. The festivity also involves the worship of Saraswati, the goddess of learning in particular during the last three days of Navratri. This is the time by which children in Kerala are introduced to the alphabets and a ceremony called Vidyarambham goes on.

North India (Ramlila and Dussehra): In North India, Navratri is synonymous with the legends of Lord Rama in the epic Ramayana. The festival finishes on Dashami when, along with prayers to Ma Durga for her victory over Mahishasura, Ramlila concludes. The burning of effigies of Ravana, signifying the victory of good over evil, occurs on Vijayadashami or Dussehra. This day is also known as Durga Shakti Dikshanam and the victory of Durga over Mahishasura.

The Significance of the festival in Modern Times

In today’s India Navratri has evolved as cultural, spiritual and social time of year. It is not just a sacred festival, rather an affair of the community. art, and ancestry. It’s a time of rebirth for many — spiritually and personally. The nine days are considered a time for self-reflection, fasting, and devotion to duty ensuring that devotees regarding their potential are most valuable and virtuous.

Moreover, it also highlights the strength of feminine power and the significance of women’s empowerment as females play a crucial part in shaping society equally here the value of both masculine and feminine force. Music, Dance and Visual arts are also a significant part of the Navratri celebrations being elaborate forms of artistic expression. Navaratri is a festival stretching across 8–9 days all over India from the Garba nights in Gujarat to the Durga idols in Bengal itself and awakens creativity and community engagement.

Conclusion

Navratri is a festival with deep historical and mythological roots that transcends mere religious observance. It is a celebration of the victory of good over evil, the power of the feminine divine, and the importance of community and tradition. Over the centuries, Navratri has evolved, absorbing local customs and practices, and continues to be a dynamic expression of devotion, culture, and creativity in modern India. As it brings people together in joy and reverence, Navratri remains one of the most cherished festivals, reflecting the enduring values of Hindu culture and spirituality.

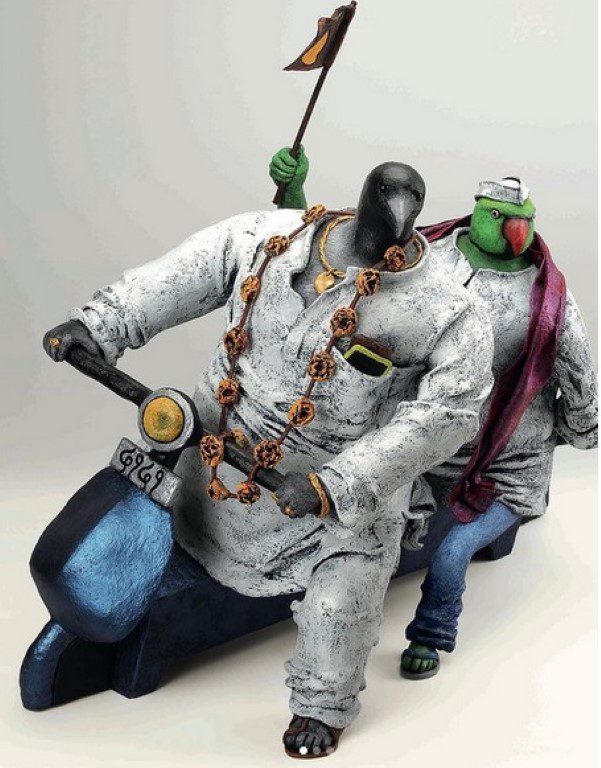

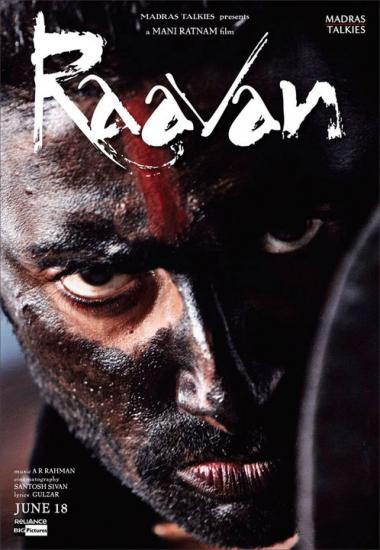

The 9 Depictions of Ravana Across the Subcontinent

Ravana, a central figure in the Indian epic Ramayana, is traditionally known as the ten-headed demon king of Lanka who abducted Sita, leading to a war with Lord Rama. However, across the subcontinent, his character has been depicted in numerous ways, reflecting different cultural, religious, and regional perspectives. This essay explores 11 unique depictions of Ravana across South Asia.

1. Ravana in Valmiki’s Ramayana (India)

Ravana is the antagonist in Valmiki’s Ramayana, representing adharma (unjust). He is portrayed as the powerful, conceited king whose downfall is due to his pride and lust for Sita. The ten heads signify his vast wisdom but also the uncontrolled ambition and ego of Ravana. It is this conventional representation that often finds more room in the mainstream understanding of Hindu culture, particularly in North India where we burn Ravana every year during Dussehra to celebrate the power of good over evil.

2. Ravana in Jain Literature

In other literature, specifically Jain texts, Ravana is portrayed as a noble hero who adheres to his dharma. Jain texts such as the Padma Purana depict him as a Vidyadhara (guardian demigod) king. His behaviour is viewed as less wicked but the outcome of multiple events, thereby underlining his multi-faceted being which is a constant strain in South Asian religious traditions.

3. Ravana in Sri Lankan Culture

Many in Sri Lanka consider Ravana their ancient hero and a great king who ever ruled Lanka. Rama is perceived to have wronged, what many as Sri Lankans regard as their deposed sovereign, whose invasion by Rama was an attack of aggrandizement and injustice. Also, Ravana was not a legend as a warrior and administrator but also he was the erudite of all time and had knowledge in playing Vina hence his vina constitute famously known as Ravanahatha.

4. Ravana in Thai and Khmer Traditions

Ravana is reborn as Ravanapangu in Southeast Asia; and Thotsakan-Thailand and Krung Reap-Cambodia In either culture, Ravana appears in their traditional dance-dramas such as Thailand’s Khon and Cambodia’s Lakhon. They show him here as this muscular and grand figure, making sure to highlight his fighting prowess and kingly status. Instead of being a devil, he is often depicted as tragic hero who contained elements of hubris and excessive pride.

5. Ravana in Tamil Nadu

In Tamil Nadu, Ravana is remembered as a devoted follower of Lord Shiva, and as a great scholar and capable ruler. His vast learning in the Vedas is mentioned often in local mythology also how he did penance to shiva. In fact, Ravana is even included in some temple iconography of temples such as the one from Tamil Nadu which tell us how deep rooted his character is in Dravidian mythology He is also known for his mastery in music within southern classical traditions.

6. Ravana in Karnataka’s Yakshagana

Yakshagana, a folk theatre tradition of Karnataka will often portray Ravana in this complex way. And whereas the character of Ravana in Valmiki’s Ramayana is portrayed as a complete villain, here the players bring about his inner turmoil, which involves love for Sita and duty to his kingdom through Yakshagana performances. They all perform as heroes or heroes unsung after their bravery, and intelligence to the trap of destiny feeling as a tragic hero.

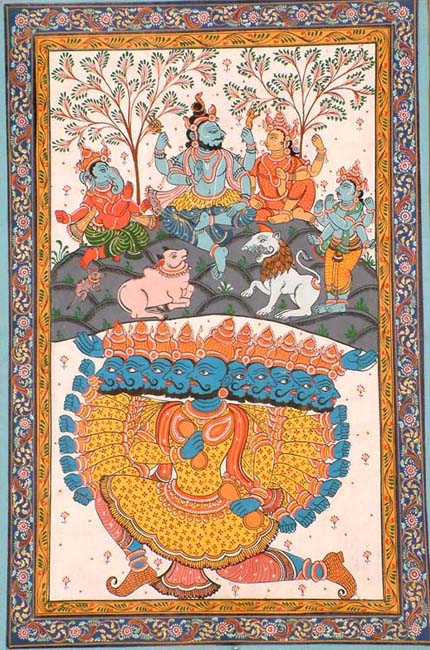

7. Ravana in Odisha’s Pattachitra

The Pattachitra art of Odisha depicts the exiled king in all his mythological grandeur. In art, he is a towering splendour of millenial sunshine imagery set against the backdrop of war and empire. As intricate paintings narrate, Ravana is not just a villain, he is much more than that — a symbol of power, a fierce warrior whose downfall serves as a grim reminder of the ephemeral existence of authority.

8. Ravana in Indian Classical Music and Dance

Ravana, the demon king of classical Indian traditions was considered an ardent devotee struggling against demonic influence. In the legend of Ramayana, Ravana was a highly skilled musician, and his prayers performed by singing were celebrated in Carnatic music. Some Bharatanatyam and Kathak dancers showcase Ravana as a man driven by passion but misinterpreted, for his music and intelligence.

9. Ravana in Contemporary Popular Culture

This is also the reason why Ravana has been revitalised in modern art, literature, and film in recent years. In Ravana’s secular God, popular cultures (from Bollywood to regional cinema) have similarly constructed the image of a tragic anti-hero as opposed to an evil figure: a tragic hero endowed with love, duty and fate. This extra- humanised depiction has grown particularly trendy in modern-day renditions of the Ramayana, which pull attention to the extent and complexity of Ravana.

Conclusion

Ravana as a figure, traverses the subcontinent and appears in a variety of forms- depending on region, art form, tradition etc. The many interpretations of Ravana, ranging from a demonarch villain to a god-king and tragic hero to the symbol of illimitable foibles in human beings, represent the diverse hues in South Asia. As such, these representations are a reflection of the fact that even the greatest villains in mythology have always been far from one-dimensional, and their narratives change to suit our time.

The Cosmic Significance of Indian Gods and their Vahanas

The mythology of Indian gods and their vahanas is a rich tapestry woven through with symbolism and spiritual depth. Just as divine mounts, these vehicles also signify the cosmic role that the deities play, who they are, and their abilities which reflect in their personalities. The idea of gods riding vahanas takes root in ancient texts like the Puranas and the Mahabharata, but over time has come to represent broader philosophical notions in Hindu cosmology.

1. Vishnu and Garuda: The Symbol of Speed and Devotion

Garuda – the vahana of Vishnu (the god who sustains the universe) is a magnificent eagle-like creature associated with speed, strength and the ability to transverse through various cosmic realms. The image of Garuda represents loyalty, and devotion even despite the bounds of segregation depicting that truth and divine knowledge has no barriers. In contrast, Garuda due to his ability as a swift bird is able to manoeuvre through the celestial plane transporting Vishnu wherever protection of life is needed. Garuda had the unflagging love and even his liberation story. Garuda is known in the Hindu mythology as having been born to make his mother free from slavery and thus became a model of sacrifice and righteous struggle. Garuda is also revered as a god in his own right, embodying the virtues of loyalty, duty, dedication and single-minded devotion to a cause.

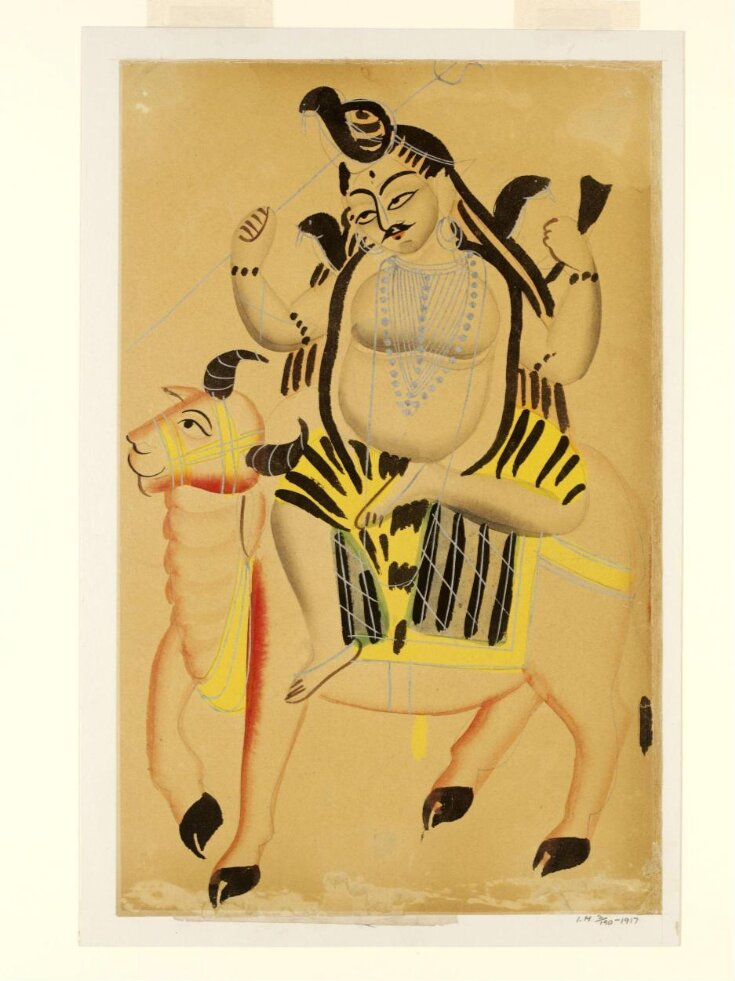

2. Shiva and Nandi: Strength and Devotion in Harmony

The tough, strong, and powerful bull Nandi representing virility, power and strength on which the god of destruction as well as transformation Shiva is traveling. The bull which is widely considered as a symbol of patience & tenancy, exactly fits with the nature of both creating (earth fills) & destroying(i.e land settlement). Nandi is associated with discipline and devotion, guarding the doors of Shiva’s temples, as well being a principal servant or vahana of Shiva.

Nandi as a dharma and moral justice icon in Hindu mythology Shiva contrasts against his bull in a more fiery temper, representing the destructive side to Nandi’s harmony — the balance of destruction and calmness that truly characterises the cosmic rhythm. Nandi’s devotion to Siva is a theme for the message that everlasting peace can only be achieved from strive the spiritual path and righteous living.

3. Durga and the Lion: Courage, Power, and Protection

Durga, the warrior goddess of protection, sits astride a lion which denotes courage and strength to fight evil. In battle domestic scenes Durga frequently seems sitting astride a lion combating the demons. As a lion is the king of beasts, he signifies absolute power and majesty, a reflection of Durga’s protective and destructive ability. Mythologically, the lion is not simply her ride but also an extension of Durga’s shakti (or divine energy). This shows her power over the physical world and control of nature and the supernatural. The lion also reminds us that the war against justice needs more than brute power, but it needs mental acuity and a deep passion.

4. Ganesha and the Mouse: Humility and Overcoming Obstacles

Ganesha — Remover of Obstacles and The God of Wisdom riding on a Mouse/Rat. This would seem at first quite an odd couple, as Ganesha is a great deal larger and more imposing with his elephant head (both much bigger than the tiny Mouse). Nonetheless, that distinction brings into sharp relief the notion that no obstacle is so insignificant as to be insurmountable and that even the tiniest of beings have their niche in what some perceive as divine Will.

The mouse, known for slipping into the tiniest of holes, signifies how Ganesha helps you remove hidden obstacles from where one could least expect them in lives. Further the mouse stands for human desires, that Ganesha masters and puts under his control. His control over the mouse signifies man’s effort to control his greed while Ganesha’s head symbolises spiritual purity and spirituality.

5. Kartikeya and the Peacock: Beauty, Pride, and Knowledge

Peacock As his Vehicle peacock uses its long majestic feathers signify bravery and cleverness, and also to send away the ignorance of darkness. Kartikeya is the commander of the divine army and holds a peacock in his hand which means a symbol of learning against ignorance, and spiritual against material. Then I realised that the image of a peacock, represent all colours tones and shades in their vibrant form symbolising unity in diversity -just as Kartikeya unites various lost souls from mazes and chaos of life. Peacock — sign of renunciation and detachment from the sensual world, a Peacock doesn’t get affect by sensuality as its associated with war & disciplined Kartikeya.

6. Saraswati and the Swan: Purity and Discernment

Goddess Saraswati, known for wisdom and arts, often rides a swan. Swan as an allegory is purity, beauty, and discernment able to bring milk from water – meaning that it can distinguish between truth and falsehood or between spiritual and physical. Pairing Saraswati with the swan is symbolic of the male deity drawing from a female aspect of divine power which results in spiritual or religious enlightenment.

The swan is related to the Paramahamsa which means realised soul—in Hindu philosophy. Those who are believed to have achieved this state are said to move seamlessly from the physical world of material life, akin to a swan floating gracefully across the water. Thus, Saraswati has as her vahana the two highest ends of human life: the pursuit of knowledge and the development of inner purity.

Lakshmi and the Owl: Wealth, Wisdom, and Vigilance

A Vahana in itself is a symbolic object, as seen for example with the goddess Lakshmi who always carries an owl. Although the owl in and of itself can be an odd choice, it offers a range of symbolic meanings. According to Hindu mythology, owl is associated with wisdom, vigilance and the ability to see beyond illusion. Because the owl is Lakshmi’s vehicle, it shows prudence and discernment are always to be applied when seeking wealth or material fortune. A lesson that prosperity without wisdom can also meet ruin. Further, because the owl is a nocturnal bird, it symbolises clear sight through darkness, meaning that true wealth cannot be calculated in material terms alone. All this combines to make a statement about the kind of common-sense and alertness our world demands when it comes to gaining and using money — about finding that compromise between material treasure and moral goodness.

The Deeper Symbolism of Indian Gods and their Vahanas

On a symbolic level, the vehicles of Indian gods offer deeper allegorical insights—each revealing unique characteristics about the divine nature and purpose of its rider. Vahanas are bridging the gap between humans and their spiritual journey, interpreting things for them. The material and the spiritual, mundane and cosmic; balance between the two is an essential practice, reminding everyone of this dichotomy life. After all, these divine vehicles represent the vehicles that gods use in their relationship with people. As Indian gods and their vahanas are a synergy of loyal service, devotees are reminded to serve the divine meekly, in humility and surrender.

Conclusion

The notion Indian gods and their vahanas in Hindu myths reinforces the idea that gods, their qualities and energies cannot be separated from each other and also explains how various lessons on ethics or spirituality related to mankind are somehow associated with these amalgams. It could be Vishnu riding on Garuda symbolising protection from righteousness or the Ganesha riding his mouse epitomising, overcoming smallest of obstacles; these vehicles play an integral part of the religious and philosophical orientation within Hinduism. The tales and meanings behind these divine beings impart evergreen wisdom, reminding us that in the grand scheme of things, the fact remains: every being has a purpose; every challenge can be scaled by stepping forward with prayer and dignity.