Ashok Vajpeyi in conversation with Piyush Daiya

Editor’s Note

On Nilima Sheikh’s birth day, let’s look at Ashok Vajpey’s impression of her Art.

Poet and cultural cognoscenti Ashok Vajpeyi is turning 85 this 16th and is documenting his memoirs with writer Piyush Daiya. As part of the memory project, we are publishing his detailed impressions of four women artists. This is the first of the four-part series.

Read the second part (Arpita Singh); third part (Nalini Malani); and fourth part (Mithu Sen)!

Meeting Nilima Sheikh

My first real introduction, or rather interview, with Nilima Sheikh happened in Bhopal when we curated a joint exhibition of four women painters – Arpita Singh, Nilima Sheikh, Madhavi Parekh, and Nalini Malani.

There’s a feminine delicacy in Nilima Sheikh’s work. Her art expresses itself in subtlety and great attention to detail. In a way, she is a painter of human suffering in our times. Or rather, I should say that, on one level, she is a companion to her life partner Ghulam Mohammed Sheikh, and on another, to Arpita Singh. All of these painters, in a way, are chroniclers of the human suffering and irony of our time.

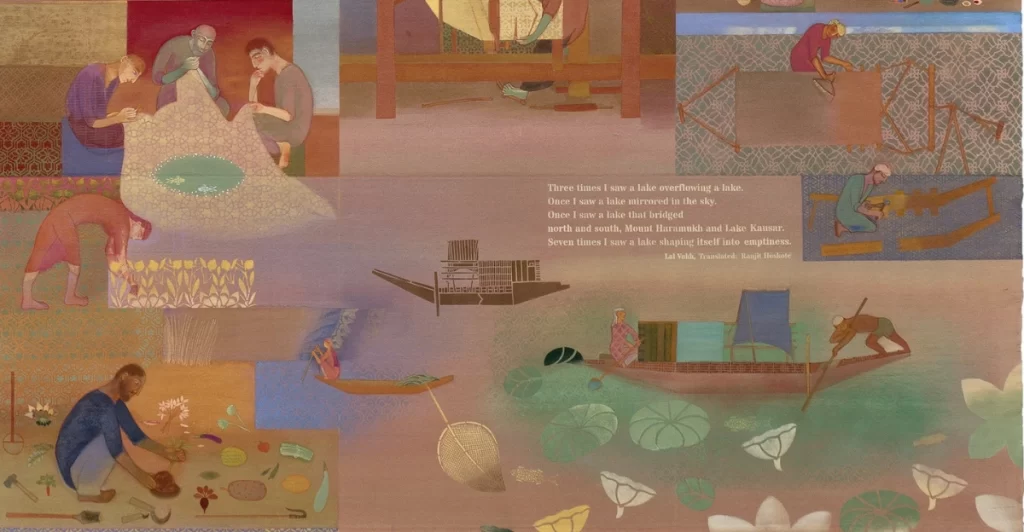

Scroll painted on both sides, Casein Tempera on Canvas

Courtesy – Nilima Sheikh

Later, my attention was drawn specifically towards Nilima Sheikh when she created several scroll-like pieces on Kashmir, in which she tried to capture Kashmir’s social and cultural pain, using verses from old poets. There is diversity in her work. She isn’t limited to just canvases and wall-hung paintings. I remember when she had created backdrops for a colour presentation by Anuradha Kapoor and Maya Rao. They were very powerful.

In the broader landscape of Indian culture, a tradition of women has been formed: for instance, the Theri Gatha, Lalleshwari, Akka Mahadevi, Meera, and Andal. In this tradition created by poetesses, there’s a profound questioning of the given religious and social order. Though they are painters, Nilima Sheikh and Arpita Singh should be seen within this tradition. But this is their true inheritance, the inheritance of those who have till recently been called ‘mad women’.

In the case of women, there is a double layer of human suffering within our social structure. On one side is the agony, the pain, and the irony of being a human being, and on the other is the pain of a woman’s situation in a patriarchal society – a double suffering. Therefore, there’s more depth and poignancy as it addresses both types of suffering.

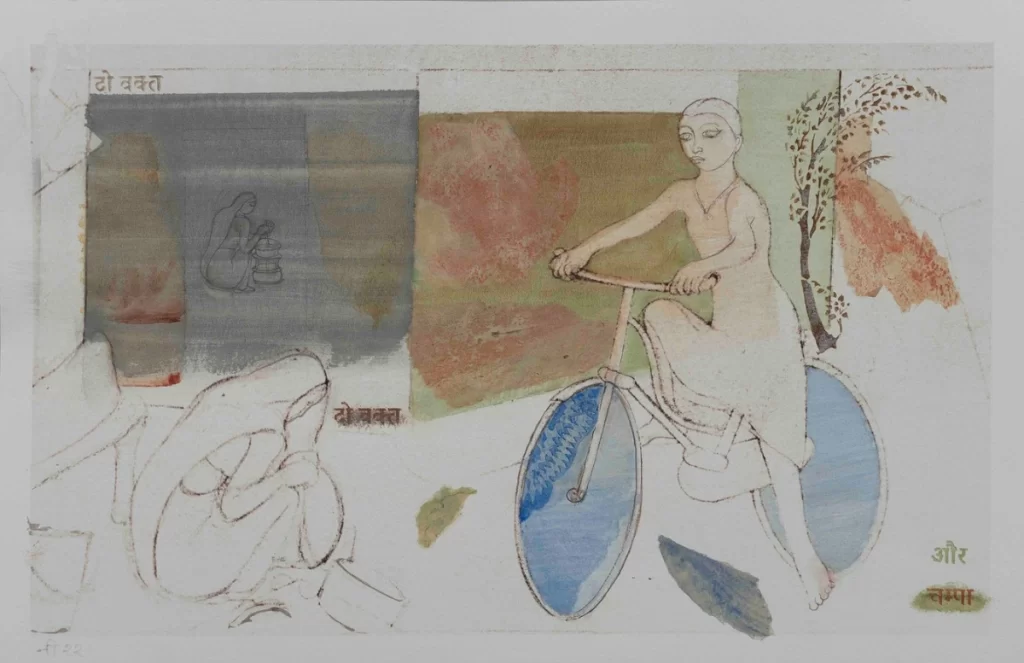

Mixed Media on Handmade Paper

Courtesy – Nilima Sheikh

In the community of those working with subtlety, we have Nasreen Mohammedi, Arpita Singh, and Nilima Sheikh. Later, Nalini Malani chose a different path. Overall, at a skill level, these artists’ work is subtle and complex. There isn’t any kind of makeshift approach.

The Tableau

I don’t know how long it takes Nilima Sheikh to create a painting, and how much time she spends, but the kind of paintings she makes, seem to require a great deal of labour. She doesn’t carry the burden of her erudition. It is an internal knowledge, an inward flow—it doesn’t overwhelm the painting’s language of colours, visual language, or forms and shapes. It’s a kind of humble wisdom, which, while present, doesn’t flaunt its being, at least not in the painting.

Tempera on Sanganer Paper

Courtesy – Nilima Sheikh

In Nilima Sheikh’s work, the large figures evoke memories of Ajanta-like tableaus. Because they are on scrolls, the tableaus are larger, as opposed to being drawn on the very still medium or object of rock – they are drawn on a hanging panel. There’s a strange contrast between the two. The rock is immovable; the picture on it is, in a way, mobile, and Nilima ji’s tableaus on scrolls are both mobile. This kind of contrast can be seen.

Narrative Quality

Apart from Nasreen Mohammedi, a few women artists have been attracted to abstraction. Apart from Nasreen Mohammedi, I cannot immediately recall any other major woman artist who has been drawn to abstraction. But there are a few. On the other hand, it is also true that most women artists have worked in narrative and figurative styles. I think women are habitual to tell stories. This storytelling tendency, often, changes to telling their own story as well. In a way, women tell both stories – one of the old neighbourhoods, or animals and birds, or something else, and another, their own story. Perhaps, the more intense and talented women merge the two – such that the story seems to be someone else’s, although it is theirs. Maybe, this tendency has also influenced modern women artists. This can be extended to all women, but at least, this is certainly an Indian woman’s quality. On the contrary, it can be said that no woman is present among the major narrators. Take for example, the epics that have been told in our part of the world—the Kathasaritasagara, the Mahabharata, the Ramayana, etc., and the later Padmavat etc. However, women mostly create folk literature. So, I understand this as a more folk-centred tendency, although most modern women artists are far from the folk, it has somehow taken root in them somewhere.

Women and Existential Awareness

We shouldn’t look at the matter in terms of woman and man because that limits our view and often prevents us from observing the artwork in its totality and polysemy. But if we think about this difference, it is difficult to believe that existential awareness is higher in men. Perhaps, it appears more clearly in men and vaguely in women due to hesitation or taboo. Broadly speaking, existential awareness is relatively lax in both. There is a widespread lack of the kind of self-awareness from which this would be a result. We exist somewhere in our basic existence beyond history, society, culture, tradition, etc.—I think this will apply to very few people.

Courtesy – Gallery Espace

Presenting a woman as a woman has often been against social, ethical, cultural, and religious boundaries. The desire to be free from the taboos lost in society, that transcend language, is an honest aspiration and a very fruitful aspiration in a creative way.

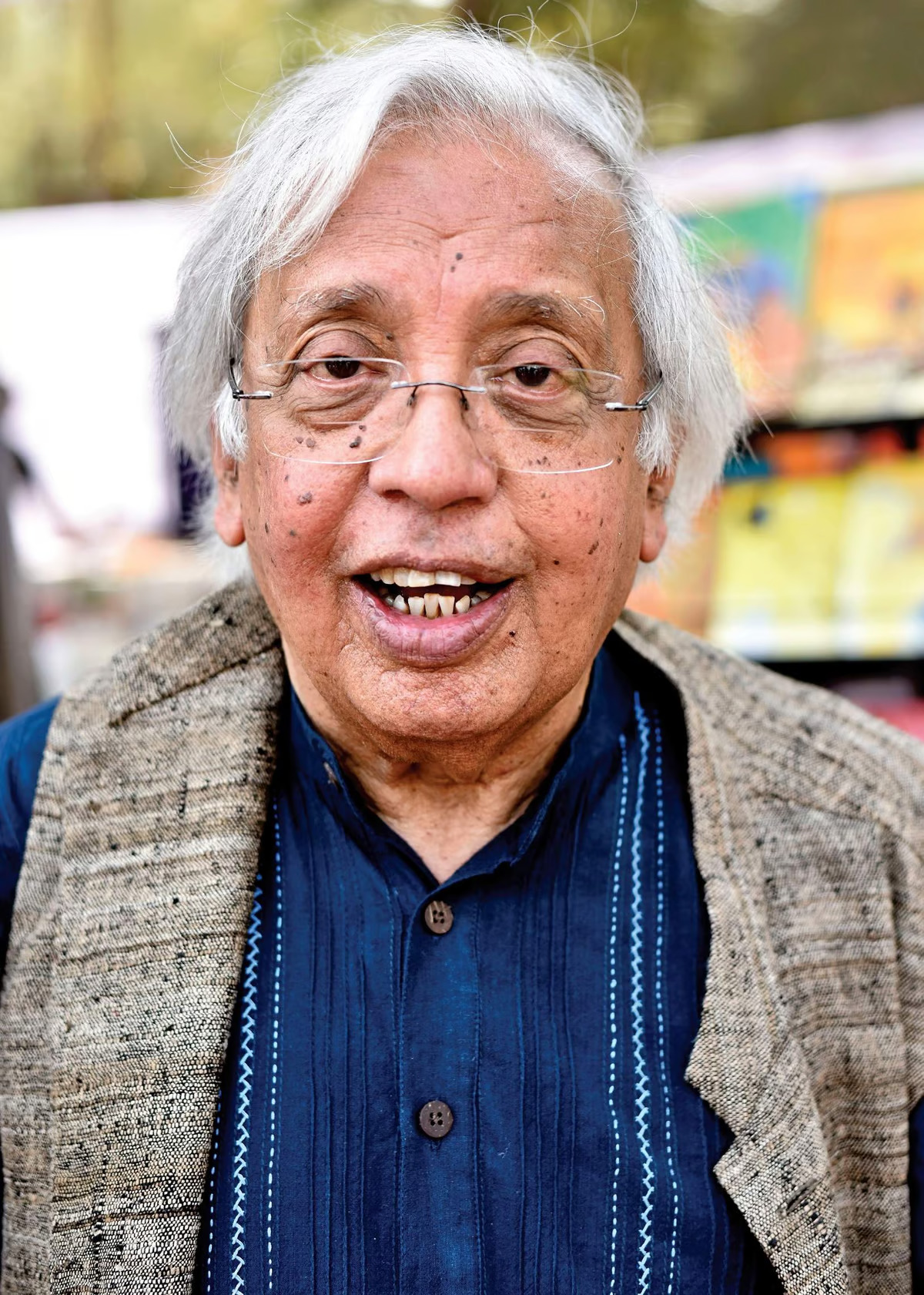

Image Courtesy – Sunday Guardian

Ashok Vajpeyi is a Hindi poet and critic with fifteen books of Hindi poetry and volumes of criticism on Visual Arts, Literature, and Indian Classical Music to his credit.