Ashok Vajpeyi in conversation with Piyush Daiya

Editor’s Note

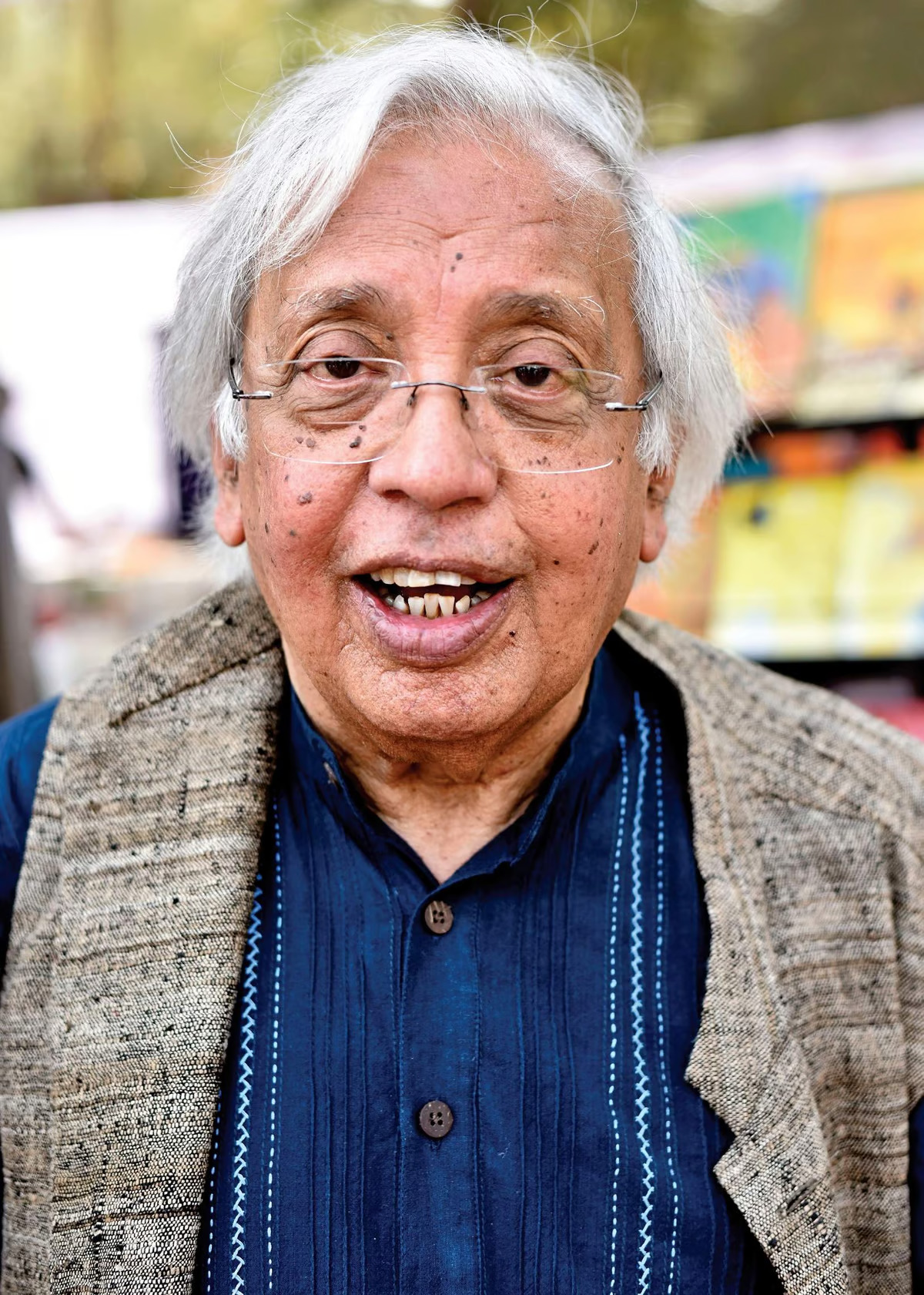

Poet and cultural cognoscenti Ashok Vajpeyi turns 85 today and is documenting his memoirs with writer Piyush Daiya. As part of the memory project, we publish his detailed impressions of four women artists. This is the fourth of a four-part series.

Read the first part (Nilima Sheikh); second part (Arpita Singh); and third part (Nalini Malani)!

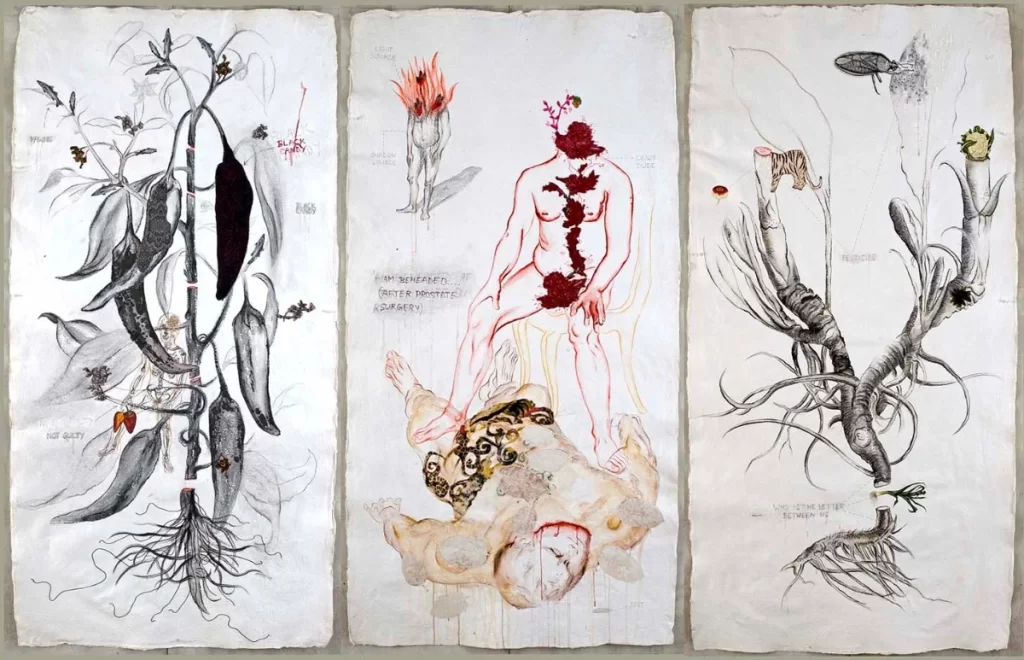

Mithu Sen’s Art Style and Theme

There is deep resentment in Nalini Malani’s work, and so is in Mithu Sen’s work, but along with that, there is also a perspective of humour. She also has a taunting tendency. Like, in one of her experimental artworks, she has done something with the gender. This way, she has a habit of taunting. The other feeling is that there is nothing that cannot be the subject of art – whether it is the human body, the human condition, or its surroundings, etc. This is also a proof of a kind of freedom. Many of her paintings start from here and go on like this, they will also go to the roof. Freeing the painting from the canvas, and seeing and being able to create the painting as a synthesis of many moods, are all qualities in Mithu Sen’s work.

In the meantime, it was a coincidence that modern Indian art got some access and recognition in the world. Because of that, many artists started getting invitations to go and spend time in various workshops, museums and such institutions or art events. For example, Mithu Sen is somewhere in a workshop or art camp three or four times a year—sometimes in Brazil, sometimes elsewhere. She keeps sending me messages from there. This aspect has also made artists like Mithu Sen a part of a world movement, more actively and more consciously. That movement, in a way, can be said to be like all the movements of art, ultimately being movements of liberation. Movements of liberation from some condition or tendency or difficulty.

Modern Indian art, with a few exceptions, has not tried to challenge or reject common morality in its art with much fearlessness or audacity. Akbar Padamsee created ‘Digambara‘, and there was an uproar over it! There are very few such examples. We can take Souza. There has been less effort to directly question the confines of many social beliefs. In this matter, Mithu Sen and some other artists like her, whose important role becomes important is that they have, so to say, broken taboos in broad daylight.

Courtesy – Mithu Sen

Many times, it happens that when you break a taboo or do some kind of innovation, it doesn’t look like art at first glance. Many times, if art is somewhat active for social purposes or political or ideological goals, it is often only a shallow type of art. It becomes a slogan or poster. Some artists have remained untouched by this happening. For example, Mithu Sen. It has been difficult to accept her art easily, but she has made a place for herself. In one sense, this questioning is more radical. It is radical in the sense that Mithu Sen and artists like her have shown the boldness and fearlessness to directly address or question the female body, all the ethical taboos associated with it, or the encirclement of various powers in our time.

The core of Mithu Sen’s artistic work, in a way, is her linguistics, which she has consistently used. In the way of seeing art, ‘seeing’ is the central word, in which the visual sense is central. It does not remain just that in Mithu Sen’s work; there the text is also equally central – she deconstructs and transforms the text (in the same way) into great meanings.

Mithu Sen and some other artists have also been very sensitive to the language of words, the language of literature, and poetry, besides their artistic language. Often, these artists paint the poems of modern poets or have continued to do such experiments. Mithu Sen has used words in both of its meanings—in its literal meaning and in its visual meaning—to expand the scope of her art. This is very important. This effort is being made on a broad level all over the world. Therefore, Mithu Sen has also joined that community.

Transformations of Roots and New Linguistics

In the context of innovative art, the question of roots gets entangled in many ways. The first entanglement is what is the relationship of talking about roots in art with elements like tradition, history, culture, etc. The enthusiasm for creating new linguistics in innovative art can also be linked to the linguistics of miniature painting – there too, the use of verbal language has been done on a large scale. Although, that language is the language of previously composed poetry. The language of previously established raga structures and raga malas. There is linguistic presence in miniature paintings.

Let’s take installation. We have a long folk tradition of installation in our part of the world, it is among tribals, it is in folk practices, it is in folklife – in its basic elements, there is a natural acceptance of the fragility of creation. Artists have seen installation as a form of modern art. Of the artists using this medium, unfortunately, none has ever even mentioned this long and widespread tendency of installation present in folk traditions. Mostly, it came from the influence of the West. Because it started in the West, it reached the extreme, where a great painter, Damien Hirst, just took out his blood, put a dead animal, or made a living person stand. Etc. This is reaching the extreme.

Courtesy – Mithu Sen

We have no special basis to believe that those who innovate have weak roots. After all, there have been so many innovations in our tradition, if the roots are weak, then how did the innovations happen? In my opinion, it is an unfounded bias that experimentation innovation fearlessness or questioning are all such proofs that your roots have been shaken or that they have become weak. It is not like that. It should also be kept in mind that new roots must be formed. It cannot be that a tree that has grown in a new era will have the same kind of roots as before. Now the nature of the soil has changed, the colour of water has changed, and there have been many changes in rain and climate – what will the roots of trees be like now, and how? I don’t know whether the specialists in botany have noticed these changes in roots or not. But using it as a metaphor, we can say that if such innovation or such questioning or such fearlessness is possible only from being rootless, then we should welcome such rootlessness. Therefore, this scale or this conjecture whether the roots are there or not is a useless scale and a useless conjecture.

The More Fearless, the More Extreme

If we look at the case of innovation or fearlessness and any kind of radical breakthrough, Hindi literature is a little backwards. Innovation in Hindi literature is a limited kind of innovation, it does not have that recklessness, nor that rugged beauty which would sharpen it, intensify it, or make it a version of deviation. This will also apply more or less to the whole of Indian literature. Take two examples. Nirmal Verma is very powerful in his thinking, and his vision, he is fearless, and he has deep questioning in him. But the structure of his narrative language and narrative form is, on the whole, realistic. Ultimately, the structure in Nirmal Verma’s work—of language, of form, of narration—is fundamentally realistic. Reality itself has been seen with great sensitivity, with great subtlety, there is also elegance in it. The narrative literature of Krishna Baldev Vaid is exactly the opposite of this. If we leave aside his first two novels, “Uska Bachpan” and “Guzra Hua Zamana”, then he demolishes all elegance. What Mithu Sen etc. are doing now, Krishna Baldev Vaid had already done forty years ago. The more fearless Vaid is, the more extreme he is. Vaid has not been accepted to date.

There has been relatively less fearlessness of this kind in Hindi poetry. Although Akavi was there, he tried to do it a little bit, but he could not write poetry. It is possible that someone may not like Vaid’s literature, but no one can say that he has not created literature. There is demolition in Muktibodh’s work, but, on the whole, it is in the structure of reality, the demolition is within that. In a way, in Hindi, acceptance of fearlessness, moral questioning, and abstraction has not happened to date.

Courtesy – Mithu Sen/Chemould Prescott Road

I think that its reason is the ethnic mind of Hindi, which is very evident from the politics of the last ten years. There is now beginning to be a little stir in that mind. But how is it that the same region in which there was once immense creativity is now withdrawn from it—many miniature arts were made in the Hindi region, most of Hindustani classical music happened here, which is another example of abstraction. But Hindi language and literature remained unaffected by all these.

One reason for this is also how we think after seeing what innovation has happened in other places and disciplines. There was innovation in miniature painting, and there was also a little innovation in its concurrent Hindi poetry, but what is the relationship between them? There is no relationship. I do not know. Bhakti poetry happened at the same time that miniature art started.

Medium is the Message

Vivan Sundaram, Mithu Sen and other artists have been left-wing ideologues. All over the world, with some exceptions, the left in art has always considered the transfer of the message to be the main quality of art. In this sense, it has also been opposed to abstraction. It feels that abstraction makes the transfer of the message unnecessary. All these artists have a connection with the left at an ideological level. If they have ever taken the help of abstraction, some of them have taken it when and then, even then they have kept it within the message transfer, there has been no place for its autonomy. Perhaps one concern of theirs has also been to be understood and appreciated, that if we move more towards abstraction and stop giving messages then people will not understand us, and the art will not be recognized. On the other hand, they have also garnered some institutional support—at the international level and in India as well. We can see the institutional initiatives of ‘Sahmat’, ‘Khoj’ etc.

I think that post-modernity has, to some extent, created a new communicability. This new communicability avoids reducing any work of art to its original intention or original message or original meaning and can convey a more complex, more entangled meaning. It cannot be reduced to a known message, such as, ‘Go, grow children of India’. New mediums have developed a new kind of communicability and there is no burden of message on it. In a way, there, the medium itself is the message. As the economist Marshall McLuhan had said, ‘The medium is the message’. There is no compulsion or helplessness or obligation to give some separate message.

Courtesy – Galerie Krinzinger

The interaction is at a conceptual level, otherwise the interaction is very weak and almost non-existent. A big proof, a big reason for what I have been calling the cultural impoverishment of the Hindi region for decades, is that there is no dialogue among the arts. Anyway, at this time, at the all-India level, the most fearless innovation, audacity, and immense plethora of material is only in the fine arts. Not even in literature compared to it—neither in music, nor in dance, nor theatre. Music, dance and theatre are the biggest victims of so-called communicability. Through innovative artists, fine art has taken risks. In the context of India, the tradition of taking risks is the strongest in the fine arts. It has also become easily acceptable. The art market is one indication of that. One reason behind this is the arrival of that art on the international stage; it also has an influence. Internationality is a big element in the world we are living in.

Image Courtesy – Femina

Ashok Vajpeyi is a Hindi poet and critic with fifteen books of Hindi poetry and volumes of criticism on Visual Arts, Literature, and Indian Classical Music to his credit.