Digvijay Nikam

“The exotic in the painting doesn’t really interest me because the novelty of it wears off very easily whereas our day-to-day thing interest me because it is there all the time – a person sitting on a chair combing his hair. You see them totally unaware. And that is what interests me, how they look in their own surroundings.”

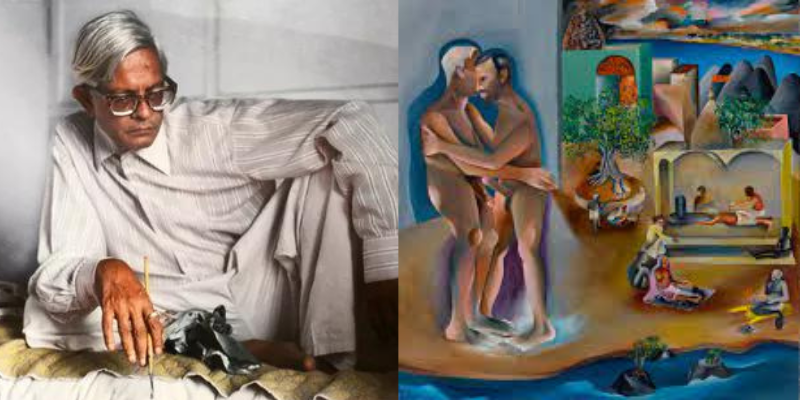

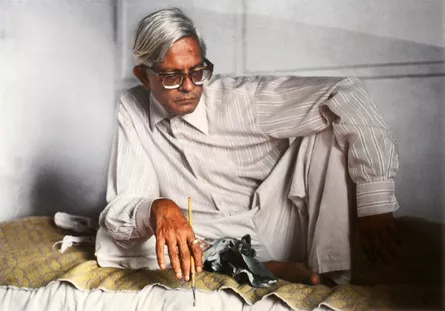

– Bhupen Khakhar

Recently, a movie titled Everything Everywhere All at Once made a huge success all over the world. At its core was the idea of having to lead one kind of life despite the multiple simultaneous exotic possibilities our existence is capable of harbouring. Isn’t it immensely perplexing that these ordinary flesh and blood people around us and we ourselves could have lived wholly different lives than we actually did had we not made certain decisions? What if the Indian artist Bhupen Khakhar had never pursued his artistic talents seriously and continued working as an accountant throughout his life? Keeping the counterfactuals aside, this article tries to focus on that dimension of Khakhar’s painterly oeuvre which was interested in capturing the multitudinous lives and events that constitute our everyday existence.

Khakhar’s was a sensibility that was always attuned to the happenings of the spaces he inhabited throughout his life. In an interview, he says, “Right from the beginning I was interested in my environment, the place I lived, people with whom I moved.” This sensibility found its avenue for expression when he moved to Gujarat in the 1950s and met the poet and painter Gulam Mohammed Sheikh who introduced him to the artistic circle that was taking shape around the newly found Faculty of Fine Arts in Baroda. Khakhar, Sheikh, and others eventually came together to constitute what is known as the Baroda School – a collective of artists who encouraged modernist ideologies and individual self-expression while departing from the revivalist inclinations of the Bengal school and academic realism practised by European schools. Here, in the beginning, Khakhar experimented with several mediums and subjects and garnered attention for his engagement with popular culture in his artworks.

De-Lux Tailors, 1972. Courtesy of Tate.

De-Lux Tailors, 1972. Courtesy of Tate.

However, the 1970s witnessed a shift in Khakhar’s practice, which was simultaneously reflected in his fellow artists’, turn towards narrative and figurative art. He now turned his artistic attention to the ordinary world of working-class and middle-class people around him. During this period, he created a series of paintings called ‘trade paintings’ which depicted people from various professions, such as the barber, the watch repairman, the tailor, and even an assistant accountant with whom he worked.

Janata Watch Repairing. 1972. Courtesy of Guardian.

Janata Watch Repairing. 1972. Courtesy of Guardian.

Janata Watch Repairing (1972) shows a watch repairer diligently at work in a dimly lit bleak and dreary shop. Bhupen’s signature colour palette and flattened pictorial space augmenting the viewer’s perspective engenders a feeling of claustrophobia. The wall inside the shop is adorned with a row of discrete clocks, all of them putting the time roughly at half past one. Interestingly, the inordinately large watches on the walls of the shop indicate a completely different time. From their position and size, they could be depictions of watches painted on the walls of the watchmaker’s shop. This mismatch in time along with the disharmony in proportions (which one can also notice in the painting of the tailor) gives a surreal edge to the painting which surprisingly succeeds in communicating the reality of the watch repairer.

Bhupen Khakhar, The celebration of Guru Jayanti, 1980. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Gallery Chemould Prescott Road, Mumbai.

Bhupen Khakhar, The celebration of Guru Jayanti, 1980. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Gallery Chemould Prescott Road, Mumbai.

Khakhar was also a fiction writer and dramatist which is why an element of narrative creeps into many of his famous paintings. The Celebration of Guru Jayanti is a testament to Bhupen’s remarkable storytelling skill. On the surface, the story is simple – a Guru, sitting with the garland around his neck on a platform, comes to the town but is casually ignored. The exotic in the painting, like the Guru, hardly seems to interest Khakhar and the townspeople, reminding us of the ephemeral nature of the extraordinary. “I wanted to show a kind of life which is going on…so many other things happen which people don’t take notice of,” says Khakhar. The painting is a window to simultaneous happenings – a group of men chatting together, a woman throwing dirt from the balcony, a labourer carrying a gunny bag while a man irons a shirt. Reminiscent of Pieter Bruegel’s work, the painting took a year to complete.

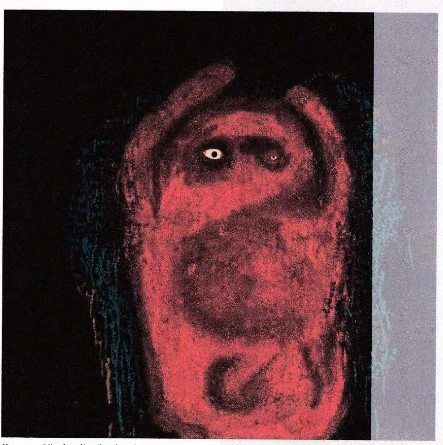

The Celebration of Guru Jayanti is a study not just of ordinary people but also a marker of Bhupen’s interest in the everyday life of religious spaces, figures, and shrines in India. Think of the wayside shrines that you encounter almost every day in your movement across the towns and cities you inhabit. What kind of relationship do you exercise with them? Often, their ubiquity contributes to our inattention to them. For instance, Hanuman, an encaustic painting that renders an iconography of the divine figure that we are all familiar with. How often have you come across shrines like these, seen someone join their hands in devotion and leave?

Hanuman. 1960. Oil on relief plaster, with incised and mixed media on board. Courtesy of Bhupen Khakhar Collection.

Hanuman. 1960. Oil on relief plaster, with incised and mixed media on board. Courtesy of Bhupen Khakhar Collection.

The writer-curator Ranjit Hoskote aptly characterises Bhupen as a natural-born anthropologist who shuttled easily between the roles of participant and observer in the various situations in which he found himself, a role which his paintings encourage us as spectators to adopt as well.

Artistic creation and reception, above anything else, are a response to the predicaments of the ‘present.’ In the contemporary world where questions of queer rights are generating unprecedented discussion, Khakhar’s later paintings on homosexuality are drawing critical attention. However, given the immense transformations of ‘our shared quotidian world’ in the past few years, it is high time that Khakhar’s oeuvre concerning the Indian every day is re-envisioned and brought to light.

References

- https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/may/21/bombay-dreams-how-bhupen-khakahar-captured-spirit-of-city

- https://bhupenkhakharcollection.com/ranjit-hoskote/

- https://www.bonhams.com/magazine/22706/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wh7NThlZpKE

- https://artreview.com/ara-autumn-16-review-bhupen-khakhar-you-cant-please-all/

- http://sunpride.hk/bhupen-khakhar-figurative-paintings-directed-whole-humanity/

- https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/bhupen-khakhar

Read More: