‘Art has been used to reinforce the power of political rulers and states since the ancient Egyptians, though the relationship between power and Art has not always been smooth, writes Eric Hobsbawm in his classic analysis in ‘Fractured times- culture and society in the twentieth century, and he brilliantly narrates the problems that Art faced under the political power.

Political power always intends to control the Art, especially public Art, that easily influences and drives the public. As we know, cinema is a public Art, gathering public opinion quickly; if the movie is about an artist, it creates more concerns than anything against power. Afterimage is believed to be the final film in the renowned career of Andrzej Wajda. It is apparently about Wladyslaw Strzeminski, a prominent Polish avant-garde artist and one of the inventors of the Constructivist activity in Poland, having performed alongside Kazimir Malevich in Russia.

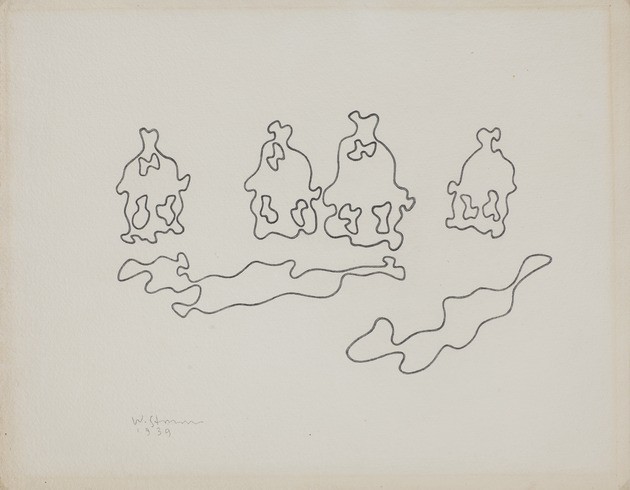

This movie talks about the life of an artist and how power operates with an artist’s career, controlled and demolished. Afterimage shows a comment about visual Art in a crushingly lifelike Stalinist drama, as argued by Hobsbawm, ‘primary function of Art under power was to organise it as public drama and led us into the political absurdism. Strzeminski was well known in the Polish art circle before the political disruption as an art theoretician, painter, innovator of ‘functional’ prints, pioneer of the Constructivist avant-garde of the 1920s and 1930s, and creator of the idea of Unism.

Strzeminski became a significant artistic influence with his work teaching and theories and revolutionary stand against the state before Art. This movie highlights his later stage after settling in Lodz, Poland; he worked as a teacher of Art and used his ideology and morals to question the state or the power.

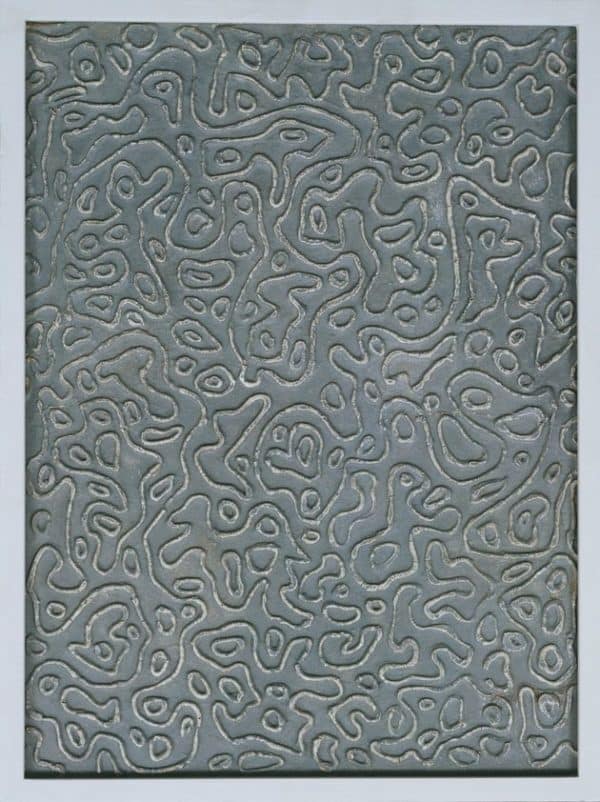

Afterimage is set in the disturbing period of the entire world, especially Europe, as we know the world war history, depicts in his afterlife ‘the lost leg’ in World War I. This movie shows what happens if anyone turns against politics or state power in Poland, that is, the Communist regime, and somewhere that maybe any other form. Strzeminski was not ready to impose state political ideology on his Art, and he focused more on abstract Art when state political machinery disagreed. An artist like Strzeminski stands against state political agenda alone, and he suffered a lot for that: the spirit-destroying orders and brutalities of totalitarian regimes, which led to the destruction of his works, revoked his memberships, and food stamps.

Strzeminski’s students tried to protect their favourite professor from this curse. Under the communist regime, social realistic doctrine kills Art; the order that shows all Art must reflect the communist significance that uplifts society and shows the proletariat’s liberation in natural portrayals. Strzeminski opposed this idea while he was an active party member, and he focused on visual anarchy in physique, declining moments of colour and space between a series of urban disorders.

Strzeminski discusses Van Gogh’s landscapes in his lecture as identical, repeated divisions and asks, was he looking at them with a usual, natural, physiological gaze? After this lecture on Van Gogh and the general theory vision, the state met in the same hall and announced the state has the power to ask the artist the most basic demands of the deeper layers of a work of Art.

The master director brings the idea of Art and power in a single film, questioning the human-state nature of being political. State orders, the artist must do social realism and fight against the ‘cosmopolitanism and servility to Western culture, and the minister argued against the Art that is formalistic and cynical, which lacks ideology. What happens to the communist idea of Art is suffering because of the weight of dogma.

If Art lacks politics and ideology, it will be the enemy of the working man, as argued by the minister of culture and Strzeminski opposing this statement. When an artist starts to resist communism verbally and visually, that creates problems.

Krispin Joseph PX, a poet and journalist, completed an MFA in art history and visual studies at the University of Hyderabad.