Krispin Joseph PX

We are living in an artificial intelligence period. AI has become a hot topic in different areas, and AI manages many intelligible contents, including Art. AI can make Art and recreate Art, and AI can read any text, even if the script still needs to be deciphered.

Reading, analysing and understanding ancient text has been challenging for human intelligence for many hundred years. The unknown script and the language that creates that text are challenging for humans, but nothing matters for AI. The significant move is AI starts to read ancient texts like Mesopotamian literature. Scholars already work with this text and read as much as possible. But the accuracy and clarity are always debatable. Reading a fragmentary text is highly problematic, and understanding the ancient world is challenging for humans. Now with the help of AI, scholars have started to analyse the ancient literature without difficulty.

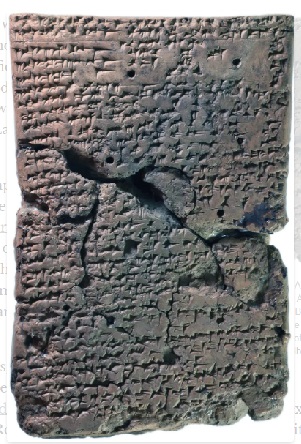

The text of Gilgamesh, an ancient Mesopotamian hero and the protagonist of the epic of Gilgamesh, is now read AI. Any innovation has changed the world of Art and culture. AI changed the art world like Photography once altered the artist’s expression and identity. The Cuneiform script is an overall and historically significant writing system in ancient Babylonia. The Electronic Babylonian Library Platform (eBL) project makes possible this extraordinary work; from the rack of British museums, this ancient text reads well.

What is going on in the contemporary art world with the help of AI is an intriguing movement to reinterpreting classical artwork and recreating unique ‘artworks’. For reading this ancient text, the eBL team reconstructed it to the fullest extent possible by AI, which helps to understand Babylonian literature clearly. ‘The project aims to provide a user-friendly platform containing extensive transliterations of cuneiform tablet fragments and a robust search tool to address the ongoing problem of the fragmented nature of Mesopotamian literature. The project’s backbone is the Fragmentarium, which digitally brings together transliterations of fragments of cuneiform tablets, clarified in the news.

These Cuneiform tablets were excavated in the 19th century and kept in different museums worldwide. The British Museum has a massive collection of fragmented tablets. Museum authorities and scholars have tried to decipher these fragmented tablets for the last many decades. Now the efforts are going to a fruitful end. The text from ancient times needs to be available for comprehension, but the textual gaps and fragmentation are riddled. ‘Cuneiform writing knows no orthography. There is no single, standard way of writing a word. Scribes, when copying traditional texts, would adapt them to their specific dialects or spelling preferences, as mentioned in the news.