Art and Life of Alexander Calder

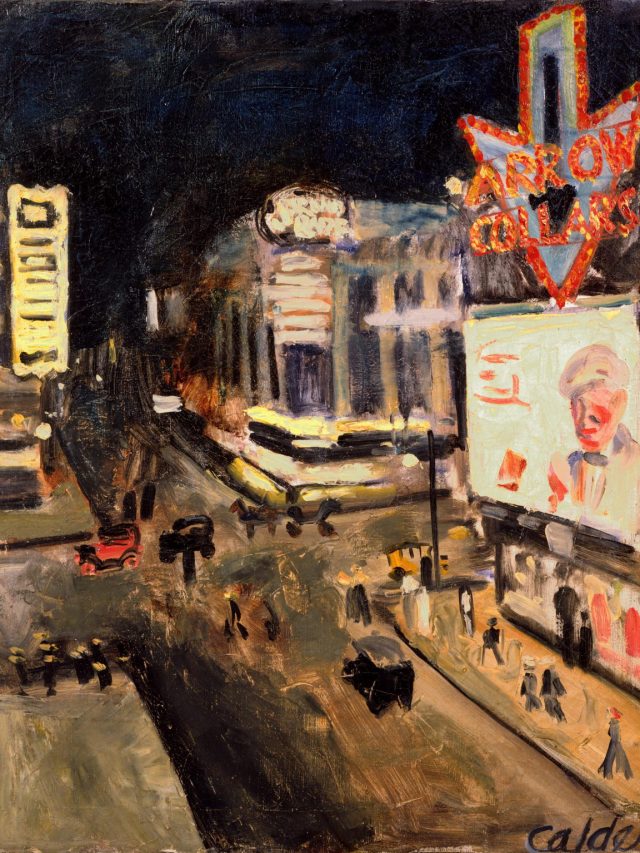

The legendary modern artist Alexander Calder transformed sculpture with his ground-breaking contributions to kinetic art and movable works. Calder’s artistic career started in a wealthy family with creative talent. His mother was a working portrait painter, and his father and grandfather were well-known sculptors. He was born on July 22, 1898, in Lawnton, Pennsylvania. His inventive approach to painting was greatly inspired by his formal mechanical engineering background and artistic heritage.

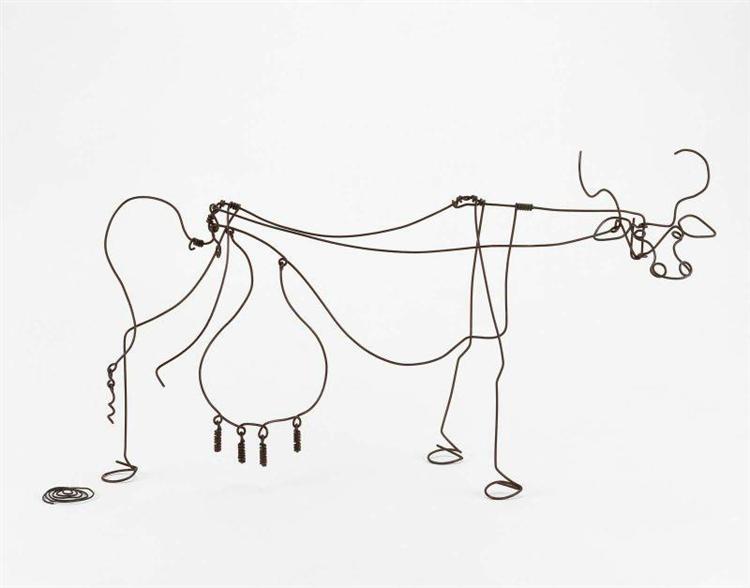

Traditional sculpture informed Calder’s early works, but his interest in motion and mechanics inspired him to investigate new artistic mediums. When he created the mobile in the 1930s—a word that artist Marcel Duchamp first used—it was a turning point in his life. These finely balanced, kinetic sculptures made of wire, metal, and bright shapes that danced with the slightest breeze created a dynamic interaction of form and space. Because of his mobiles, distinguished by their fluidity and lightness in contrast to classical sculpture’s static quality, Calder has gained a unique position in art history.

Calder’s artistic repertoire extended beyond his mobiles to include ‘stabiles,’ large, immovable sculptures that often adorned public spaces. These massive installations, with their vibrant colours and abstract designs, were a testament to his ability to transform industrial materials into whimsical, larger-than-life works of art. Calder’s contributions to various artistic disciplines inspire and influence the art world.

Calder started building “Calder’s Circus,” a tiny circus made of wire and other materials that fused performance with visual art, after relocating to Paris in 1926. This stage prepared the way for his investigation into abstraction and motion, culminating in his renowned mobile’ creation in 1931. The 1930s proved to be a turning point in Calder’s career; he moved from creating figurative pieces to creating works of pure abstraction during this time, heavily impacted by his contacts with artists such as Marcel Duchamp and Joan Miró.

The development of Calder’s art reflects a more significant trend in modern art towards abstraction. His discovery of Mondrian’s work profoundly influenced his artistic path, which led him to look for methods to include movement in his compositions. His first mobile, made in 1931, was a dramatic break from conventional sculptures limited to static forms. Calder carefully balanced the air currents these mobiles used to propel them to produce harmonic compositions that changed with the environment. Compared to mobile artworks, Calder also produced “stabiles,” stationary sculptures that maintain a sense of dynamism through their forms and compositions. His fascination with colour, form, and the spatial interactions between forms was evident in these pieces, which were frequently created from painted sheet metal. Calder expanded the potential of sculpture by utilising stabiles and mobiles, allowing spectators to interact with the work in ways that went beyond simple viewing.

Aesthetic Principles of Calder’s Work

A vibrant interplay between simplicity and complexity defines Calder’s aesthetic. He often employed bright colours and geometric shapes, producing playful and sophisticated works. The visual balance achieved in his mobiles echoes the fundamental principles of physics; his artistic practice can be seen as a blend of engineering precision with creative expression. His use of movement enriched the visual appeal of his pieces and encouraged interactions in which the audience participated fully in the experience of the artwork. This kinetic art’s constant change reflected life’s inherent unpredictable nature. According to Calder, art should welcome chance and flexibility and reflect both the natural world and the human condition. This mentality further cemented his influence within modern and postmodern discourses by striking a chord with current art groups, prioritising connection and process.

Major Works and Their Impact

“La Grande Vitesse,” a colossal stabile in Grand Rapids, Michigan, is one of Calder’s most famous creations. When it was finished in 1969, it was the first publicly sponsored piece of art supported by the National Endowment for the Arts. This significant milestone cemented the significance of public art in American culture. This work is a prime example of Calder’s ability to include sculpture in public areas and encourage contact and community involvement. His preoccupation with heavenly themes is further demonstrated by his mobiles, “Untitled (1965)” and “The Universe,” which fuse art and science in conceptual and aesthetic frameworks. The dynamic way he arranges shapes in his paintings frequently conjures up images of the cosmos, prompting viewers to consider deeper philosophical issues regarding existence and connectivity.

Calder emphasises fun in all his performances, especially in “Calder’s Circus.” This fusion of sculpture and performance art foreshadowed following trends in installation art and artist-led performance. Future artists can now explore the limits of art as a live, interactive experience because of his exceptional ability to blend visual art with dramatic components.

Calder’s Influence on Future Generations

Many artists working in various media have been significantly impacted by Calder’s inventive approach and pioneering attitude. His skilful fusion of engineering and art inspired kinetic artists like George Rickey, who contributed to the development of interactive public art. Furthermore, Calder’s revolutionary contributions can be traced back to modern artists who work with movement and audience participation. Today, many still adhere to Calder’s conceptual framework regarding the interaction between art and nature. His unwillingness to identify with any particular art trend supports the idea of creative freedom and individuality. This commitment to self-expression encourages contemporary artists to experiment with various approaches and permits the fusion of several artistic mediums. Furthermore, Calder’s creations are still widely studied and shown, which adds to the ongoing discussions in art theory about temporality and the nature of sculpture.

A Playful Engineer

Third-generation sculptor Alexander Calder did not start as an artist. “I started by studying engineering,” he remarked. However, after four years, I concluded that engineering did not give me enough room for creativity or play. When he thinks about his work, the value of play brings him back to a fundamental belief about how a sculptor should approach their chosen media.

He once said:

I feel an artist should go about his work simply with great respect for his materials… Sculptors of all places and climates have used what came ready to

hand. They did not search for exotic and precious materials. It was their knowledge and invention which gave value to the result of their labors…

Simplicity of equipment and an adventurous spirit in attacking the unfamiliar or unknown… In my own work, when I began using wire as a medium, I was working in a medium I had known since a child. For I used to gather up the ends of copper wire discarded when a cable had been spliced and with these and some beads would make jewelry for my sisters’ dolls.

Calder frequently discussed how he used to make toys while he played. He remarked, “I had a lot of toys when I was younger, but I was never happy with them. I constantly added to and developed the collection by adding pieces made of copper, wire, and other materials. Through his constant innovation and reimagining of playthings, Calder set himself up for an illustrious career producing art that inspires play.

Conclusion: Calder’s Enduring Legacy

Alexander Calder is regarded as a modern sculpting pioneer because of his creative contributions. His avant-garde ideas about movement, interactivity, and materiality upend conventional ideas about art and provide a more fully immersive experience. His paintings’ pleasure and lightness remind him of the strength of the creative process and the importance of individual agency in artistic expression.

Calder successfully bridges the distance between the observer and the artwork by using lively forms and dynamic features, promoting close interaction with the artistic experience. Calder’s legacy inspires modern art discourse, demonstrating the dynamic interplay between art, life, and the environment. His contributions revolutionised sculpture’s aesthetic standards and opened the door for kinetic art’s subsequent discoveries, guaranteeing that the next generations of artists and art enthusiasts would feel his influence.