Welcome to Samvaad, where art meets conversation, and inspiration knows no bounds. Here we engage in insightful conversations with eminent personalities from the art fraternity. Through Samvaad, Abir Pothi aims to create a platform for thought-provoking discussions, providing readers with an exclusive glimpse into the creative processes, inspirations, and experiences of these creative individuals. From curating groundbreaking exhibitions to pushing the boundaries of artistic expression, our interviews shed light on the diverse perspectives and contributions of these art luminaries. Samvaad is your ticket to connect with the visionaries who breathe life into the art world, offering unique insights and behind-the-scenes glimpses into their fascinating journeys.

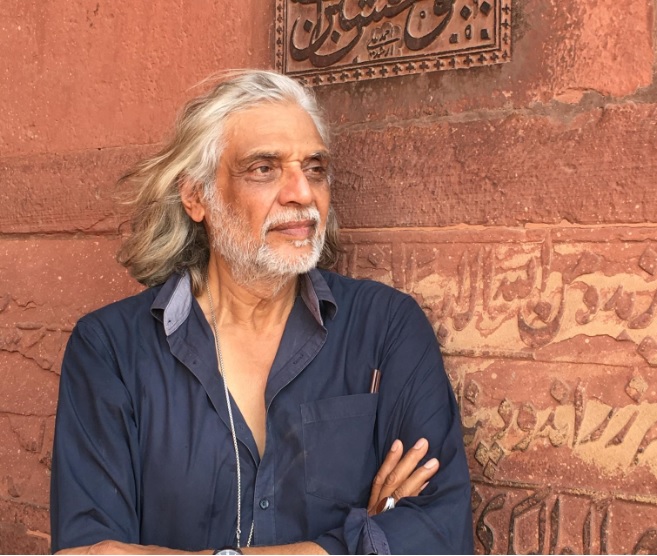

Amitabh Sarma, a graduate of Sir J.J. College of Architecture, Mumbai, brings a wealth of experience to architectural design and planning, with a focus on diverse projects ranging from residential to commercial and educational ventures. Initially cultivating his skills in Mumbai on prestigious assignments such as The School of Management, IIT Powai, and projects for Rahejas, Sarma later returned to Guwahati to establish his architectural practice. Co-founding AKAR in 2002 and AKAR Foundation in 2012, he has spearheaded numerous projects across the Northeast, specialising in large-scale developments like malls, multiplexes, hotels, and corporate interiors. Beyond his professional endeavours, Sarma’s engagement as the General Secretary of The Association of Architects, Assam, underscores his commitment to advocating for urban development policies and contributing to academic institutions, reflecting his multifaceted approach to advancing architecture in the region.

Joining us for this insightful conversation is Nidheesh Tyagi from Abir Pothi, as we uncover the visionary insights driving the creative force behind Amitabh Sarma’s design landscapes.

Nidheesh: Hello, I’m Nidheesh Tyagi from Abir Pothi. We are conducting this special Abir Samvaad at Jaquar, this time in Guwahati, as an offline initiative in partnership with Jaquar. This is important because so far, we have been conducting online Samvaad with leading Architects, and now we are going offline, especially because we are interested in tier 2 and tier 3 emerging India. So, Guwahati has been our first destination, which is probably the most distant from Ahmedabad and Delhi, where I live. Our very special guest today is Mr. Amitabh Sarma. He’s the principal architect of his own firm and has been working here for more than 20 years. He has been involved in all kinds of infrastructure changes happening in this part of the country, which includes sports facilities, hospitals, hotels, schools, residential complexes, and public projects. Welcome, Mr. Sharma. We would like to hear from you about your journey so far. You were in JJ, then you were working in Mumbai and then something brought you back to your roots, and then you settled here.

Amitabh: Yeah, it’s been a long journey. I mean, my graduation was from Sir JJ College of Architecture, Mumbai. It was way back in 1996. After my graduation, I wanted to stay back there and learn the profession, learn the tricks of the trade, rather. And I joined one of the persons whom I admired the most at that point in time, Mr. T Khareghat. I always used to admire his buildings whenever I used to travel from my hostel to my college. All the buildings that he used to do, and every time I looked at his buildings, I used to say to myself, “One day, I’m going to join his office.” So, that was the determination that took me to his place.

It took me some kind of cajoling and convincing for Mr Khareghat to take me up in his office because he was already full at that time. So, it was, I would say, 2 to 3 years of excellent experience in terms of architectural exposure, in terms of work experience. I would say, a wholesome work experience that an architect always goes through. We handled projects. We were just out of college, fresh out of college. Now, when you see a fresh graduate in any office for that matter, you’re like an intern. But we were never treated like interns in that office. It was just a small office of six to seven people, and you would be amazed to know that we used to handle projects of big magnitudes. We had clients like the IIT, we had clients like the Rahejas, we had clients like the Great Eastern Shipping, Gowani Builders, huge projects, Tata Housing, you name it. It was a small office, and my idol was this man who would sit at the end of the office at one small table, look at the Stock Exchange Building every time, and in the morning hours, of course, he would spend in knowledge assessment of stocks and everything, and the second half, he would always be there with us to share his stories and other things. He was one jolly fellow. He used to whistle throughout the day, and he made architecture look very simple to us. Whenever we were stressed out about any design assignment, he used to call us like a father figure and he used to explain it to us, “See, son, this is so simple. You were just stressing out yourself for nothing. So, this is how you’re supposed to do it.” And it was like after he tells you that, it was like, “Why were we all stressed up all the time? It was really nothing.” And that was one way of looking at things which really inspired us, which really pushed us to do things which we, at that point in time, thought we could never do. So, it was a wonderful experience. I can go on narrating stories after stories.

Mumbai is a place, I would say, sometimes you want to relate yourself to the place where you stay. Mumbai was a place, I could never relate to because it was so crowded. First of all, you feel lost. Morning, you come out, you’re with 1 million people coming out of the trains, and again getting into an office, coming back, again you are walking with 1 million people and getting inside a train. So, somehow, I don’t know, that was my formative period, so probably it was too early to judge things. But then, I had a feeling it was not the place for me. I am not for this mad rush of things. So, I need someplace where I can relate to, where I can work for myself, where I can think for myself and really realise the person I am. So then, I thought, what better place than my own place, my birthplace.

Nidheesh: One thing is that your father was also a government servant, and starting a professional course and then starting your own practice at a relatively young age would have been quite a risk. How did you navigate that change? Becoming an entrepreneur yourself, in terms of starting your own practice?

Amitabh: Yeah, that was the most challenging part. The moment I came back here, I made a point to engage myself with one of the established architects here, Mr. Gautam Barua. He already had an established practice driving here. So, instead of trying to, because at that time, Guwahati did not have too much work, to be very honest. Guwahati, or the entire North East for that matter, was just growing at that point in time. So, I thought it would be a wise decision to join somebody, learn the place, and learn how works are done in Mumbai for 2 years. So, let me just learn how things are done here first. So, I joined him for a couple of years, I learned a lot of things from him. I saw that there was a huge difference in the way of working there when I was working in Mumbai, and when I came back to Guwahati.

The difference, first of all, was there was a big cultural difference, the work culture for that matter. In Bombay, I would say it is 10 times faster than how works are done here. So, first of all, it was a big adjustment for me to adjust to that kind of pace. Then, the kind of craftsmanship or the quality of work or workmanship that you would see is the big difference. So, in terms of workmanship, I could understand that there was a lot of, I mean, it lacked a lot of infrastructure support and things like that. And you don’t have the right kind of skill set, skilled persons to undertake all the work that we wanted to do. So, initially, I thought I made a wrong decision to come back to this place because somehow, I felt I was suddenly stopped. I stopped walking, I even stopped walking, and I was like a still person. So, it took me a while to get into the fold of things.

Then, I started learning. Two or three years down the line, I started my own practice in 2002. It’s called Akar, it’s called now. That was a partnership firm, now it’s called AKAR Foundation. So, there, slowly, we started taking up projects. My father, as you said, rightly, is from that service background. So, he’s always used to say, “Finally, what is your plan? What are your plans finally? Because finally, you have to start something on your own.” I said, “Definitely, I have to start because this is a profession where I cannot expect myself to be engaged somewhere where I cannot express myself for the rest of my life.” So, I need someplace where I can really express myself. My work speaks for itself. So, he said, “Then, better late than never. I mean, you start off immediately.” Then, that’s how I started in 2002. I started my practice officially, and it started off slowly.

But then, now, by the grace of God, everything is in place. And we have almost, I would say, 20 years of practice behind us. And initially, of course, there were a lot of hiccups. Projects were very slow to come by. But if you remember, in the early 2000s, there was a big real estate boom nationally, I would say, which had its reparation here. It trickled down here to the northeastern part also. This part also had its fair share of development, and we were fortunate enough to start our practice at the same point in time.

Nidheesh: So, Amitabh, you’ve been a witness to this entire transformation over the last 25 years, which you’ve been talking about. If you were to compress it into a time-lapse video or in your own thoughts, and then convey it to us, how fast and how drastically things have changed. Because what I’m curious about is this change in non-metropolitan India, how rapidly things have changed, and then the internet arrived, housing emerged, and suddenly jobs appeared. There’s this significant emancipation and aspiration, and all of this is probably happening at a much faster pace than in metropolitan cities. So, in a way, it seems fortunate that you were in Mumbai and then moved to a place that was experiencing rapid growth. If you maintain that pace, you could reap the rewards. How would you summarise this change, the rapidly evolving landscape of infrastructure, architecture, and real estate?

Amitabh: I think I was fortunate, or rather our generation was fortunate enough to experience the best of both worlds. When we were in college, there was just a single computer in the college, so computerization wasn’t prevalent. We learned architecture the hard way, the manual way, where we used to do things with our hands. Now, everything is computerized. From day one, students are given computers to do their assignments, and everything has become digitized and electronic. It’s a good thing, and we have also adapted to that change professionally. Until you adapt to changes, you cannot really live with the times. That’s one thing I have learned over the years.

I still remember when I came back to Guwahati, and I was very efficient at handling computers. However, most offices here did not have computers. There would be one computer in an office of 20 people, and the person using the computer was like a king. That was the kind of situation we experienced. We were very fortunate to be at the starting point of that revolution. Every change, and every technological innovation, whether it’s social media or any other innovation, has its positives and negatives. So, we have to pick the positives from everything.

We have embraced the positive aspects of all these innovations, from computer-aided designs (CAD) to BIM technologies. Now, with AI and 3D printing, it’s reaching another level altogether. We have to brace ourselves for this kind of change because, as I still remember from Alvin Toffler’s book “Future Shock,” “the only constant is change, and it’s not only the change that troubles you; it’s the rate of change that troubles you,” which is exponential. We have to adapt ourselves to these changes, and we are happy to say that we would love to get along with this space.

To be continued…