Welcome to Samvaad, where art meets conversation, and inspiration knows no bounds. Here we engage in insightful conversations with eminent personalities from the art fraternity. Through Samvaad, Abir Pothi aims to create a platform for thought-provoking discussions, providing readers with an exclusive glimpse into the creative processes, inspirations, and experiences of these creative individuals. From curating groundbreaking exhibitions to pushing the boundaries of artistic expression, our interviews shed light on the diverse perspectives and contributions of these art luminaries. Samvaad is your ticket to connect with the visionaries who breathe life into the art world, offering unique insights and behind-the-scenes glimpses into their fascinating journeys.

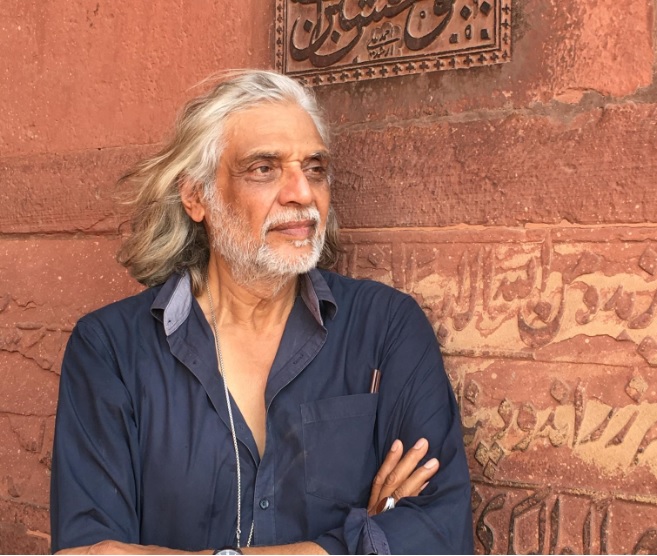

In this edition of Samvaad, we look into the world of architecture with Jignesh Modi, an esteemed architect hailing from Surat. Engaging in a conversation with Nidheesh Tyagi from Abir Pothi, Jignesh shares insights into his career journey, the architectural landscape of Surat, and his unique approach to design.

From discussing Surat’s rich history as a forward-looking city to envisioning its future as one of the fastest-growing urban centres globally, Jignesh paints a vivid picture of his hometown’s evolution and aspirations. He emphasises the importance of preserving Surat’s cultural identity while embracing modern advancements and global influences, striking a delicate balance between tradition and innovation. Jignesh further elaborates on his experiences in the field, highlighting the collaborative efforts involved in creating transformative architectural projects. Drawing from his partnership with his wife Monica, also an architect, he reflects on the division of labour, the significance of originality in design, and the value of encouraging creativity within the team.

Touching upon the evolving role of technology in architecture, Jignesh challenges the notion that complexity equates to superior design. He advocates for a human-centric approach, emphasising the need for spaces that prioritise functionality, comfort, and user experience over mere aesthetics. Throughout the discussion, Jignesh shares anecdotes, challenges, and triumphs, offering valuable lessons for aspiring architects and designers. His dedication to authenticity, innovation, and community engagement serves as an inspiration, underscoring the transformative power of architecture in shaping societies and enriching lives.

Join us as we embark on this enlightening dialogue with Jignesh Modi, exploring the intersections of tradition and modernity, creativity and pragmatism, and the timeless allure of architecture in shaping the world around us.

For Part-2 (Click Here)

Nidheesh: I also want to ask you one more thing about since lots of young artists are part of our Art Foundation and Abir Pothi. So, what do you suggest to young artists? I mean, what should they be doing to become more relevant in these spaces where buildings are coming up, and spaces are being designed? And lots of our artists come from small places like they’re not always coming from metropolitans.

Jignesh: See, rather than suggesting to artists because they are doing their job, I would rather suggest that we, as a fraternity of architects, designers, even bureaucrats, wherever we need to spread awareness about it. Just recently, I talked about this mural and this traffic island. We wouldn’t have been able to achieve it without… See, we tried doing it without an artist, but then we wouldn’t have been able to achieve the result that we got. We kind of took the services of Krunal Jhaveri, who is a fine art professor at VNSGU, the university over here, a good friend of ours. The kind of touch, this canvas touch that he lent, the textured touch that he lent, you know, kind of… If on a grade of 1 to 10, if it was at five earlier, he got it to 9.5 and humanizing it, you know, kind of. So, what we see is that if we take them in confidence, if we involve them in our day-to-day projects, not only just kind of in the finishing touches where you just hang a painting or a mural on the wall but even taking their ideas on when you’re doing a space, how do you kind of manage that space that finally the end user also enjoys it by involving them from the initial stages itself. A lot of architects or designers get the artist at the end, so that is not how it should work.

And the second thing, the question that you asked, what’s my advice to the artists? I know they are doing a tremendous job if given an opportunity, so now the opportunity to be given, I don’t think they would be able to take it up independently unless there is help from professionals, from the government, from the bureaucrats, everyone.

Nidheesh: Let me reframe this question: What should an artist do to get your attention as an architect and designer? You must have been to so many places in the world, so what kind of art personally interests you? How do you experience art?

Jignesh: I have felt one thing: Whenever I have visited museums specifically to go and look at art and admire art, I don’t know, somehow it has never worked for me. But when I am moving out on the streets and just travelling, maybe by road, by rail, airports, in my daily life, that is what inspires me. That is what gives you ideas. And I would call that accidental art, right? So, you’re travelling, you never expected to see something, you never expected to see a mural or a wall painting. You go out for walks in the morning and then suddenly, overnight, there is some painting on the wall, some mural on the wall. So, these are the things that always inspire, and attract, and that is what we look for when it comes as a surprise. And you sit there for a while, you admire it, and then you try and think about what you could do with this if you wanted to create a similar kind of space in your design or somewhere.

Nidheesh: So, we are also, you know, our generation basically, it’s also like we are steam locomotive drivers like we are digital converts. We are not digital natives. So now, the people who are coming into practice, they’re also heavily driven by technology and AI, especially. What do you think about that? How it’s going to change or, you know, on what cusp of both things, we are also, like, maybe fortunate or lucky to be part of these two changes.

Jignesh: True! See, architecture and design are something that our minds should relate to in very simple terms, wherever we are or whatever space we are exploring or being in. It should not confuse your mind; you should not think, “Okay, this looks nice, but kind of it looks complicated.” So, I think the definition of good design, maybe with young designers, is that the more it becomes complicated in terms of structure, in terms of form, the better a design it makes. But I strongly disagree with that perspective. You need software to create complicated structures and complicated designs, but why do you need a complicated structure in the first place? That’s my basic question. Okay, you have all these software which would kind of give you an idea how this can be created, so it is something which is greater than your mind that your mind can kind of think of it but cannot put it into practice, and that software will kind of help achieve that. But again, my question: Why do you want that kind of thing? Yeah, because our minds, we’ve started from caves. I’m not saying we should still be in caves or that is where we need to go back, but we are comfortable with something which is easy to look at, and easy to be in. There should be a feel-good factor about it. It should be relaxing; there should be plenty of light and plenty of natural ventilation. That’s about it. That’s what architecture and design are all about. Okay, you bring in aesthetics; you bring in all these finishing touches and all those things, but still again, we don’t want our house or office to be a museum where you can’t touch things because you fear spoiling something. It should be something where I can be freely moving, where my thoughts can freely move, where I can do what I wish and not be restricted because I am in an environment where everything is sacrosanct and I can’t touch something or feel something or be what I am.

Nidheesh: True. So, talk about your partnership. It’s like you work with your wife as your business partner as well. How do you both separate your division of labour as well as the collaborative aspect?

Jignesh: Right, it’s a very interesting dynamic. Actually, with your team, and more importantly, if your better half is an architect, it gives you a lot of freedom to do things differently, to experiment more. Firstly, I would speak about the team which I have at present, and my wife, as I mentioned before, Monica, she’s also an architect. She was my junior in college, so it started there, the collaboration. It was a social collaboration, and then it turned out we got married. Basically, there are distinct roles to be played if you don’t want to get into conflicts. Two people who are artistic in nature—I’m not so much artistic in nature, she is more of that kind. I’m a little bit oriented towards practicality, business-minded, financial aspects, and all those things, technical aspects, and all those things. And she takes care of all the soft things—dealing with the clients, the client’s wife, the client’s kids, taking care of how to take all the agencies into confidence, scheduling them, get them to do better than what they could. All that is her part. I mean, I would get angry if things are not being done, and she would kind of inspire them with encouraging words. That’s how we have made more success and met more success because of her nature to inspire people with encouraging words, soft power. And I think it’s a very important aspect because it always makes sense that you have division of aspects—certain aspects that she would take care of and certain aspects I would take care of.

Otherwise, there would be conflicts, everyone knows that, even if it’s a husband-wife team. There are conflicts if they are working on the same aspects, the same things again and again because it’s very difficult to have a meeting of minds, be it aesthetic or be it practicality. Because I would be looking at more practical kind of things, easy-to-achieve solutions. We want to kind of get over and done with. She doesn’t want to get over and done with unless it satisfies her in each and every aspect of that particular project, be it a small single wall. She would not be done with unless she’s got the last texture or the grain of color right in the end. I appreciate that, but that process, I’ll tell you, is excruciating because of certain things. The project is not getting finished. We are giving more time. But then, at the end, as I said, it matches with the theory where the end user, when he’s happy, you feel good about it. So similarly, when she’s done with it, even if it’s overshot by two months, I feel I am the end user, and I feel good about it.

Nidheesh: Exactly, that’s absolutely true. When you’re more focused on practical functionalities, you’re often inclined to get things done, to make them functional and operational. But when you introduce that sense of perfection, that finesse, it requires more attention to detail, more time, and sometimes more effort to achieve. It’s about finding the right balance between functionality and aesthetic perfection, which is where the dynamic between different perspectives, like mine and my wife’s, really comes into play.

Jignesh: Correct! Maybe, yeah. Okay, with our team, we have never encouraged, we don’t allow internet connection in the office. Because, you know, see, everyone wants, even the team, they are humans, they want to take the shortcuts. So, if you give them something to design, they might come out with certain, you know, ready-made options from the internet, from Pinterest, and they just present it to us. And it has happened with a lot of big shot architects, that when they have done certain work, they’ve given it to staff, they’ve given it to the team, they copy it from somewhere, it is there in the public domain, and then someone comes and tells you, “Copy, it’s the same thing is on the internet.” So, we from the very first day decided that we didn’t want that. We want everyone to put their mind, their knowledge, their experience into practice, whatever they do, the littlest, the smallest of details, and come up with innovative ideas and designs. And that is where I think, that’s the most important aspect of your team, your firm, your practice, everything. If you give that freedom of, you know, “Okay, get it from anywhere, just modify it so that, you know, it doesn’t look like a copy.” Then, I believe that our job becomes very mechanical, where you are copying something, you’re just modifying it, there is no originality, which, which, and that is what we are supposed to do. We are supposed to be original in our ideas so that we take care of them. And I’m proud to say that whosoever works with us, or whosoever has worked with us. I was also a teacher for almost 15 years in interior design, and the students appreciated that kind of, you know, methodology of not giving in to the easier way out. And a lot of students strived to, you know, after they finished, even while they were in college, they, they strived, they aspired to work with us because of this thought process. So, I would say that people see, people, things are difficult for you, and things are complicated for you, but people would always look up to you if you inspire them, encourage them, and always tell them to do things that are original.

Nidheesh: Thank you so much this has been such a delight to speak to you

Jignesh: thank you so much. A pleasure, same here.