Welcome to Samvaad, where art meets conversation, and inspiration knows no bounds. Here we engage in insightful conversations with eminent personalities from the art fraternity. Through Samvaad, Abir Pothi aims to create a platform for thought-provoking discussions, providing readers with an exclusive glimpse into the creative processes, inspirations, and experiences of these creative individuals. From curating groundbreaking exhibitions to pushing the boundaries of artistic expression, our interviews shed light on the diverse perspectives and contributions of these art luminaries. Samvaad is your ticket to connecting with the visionaries who breathe life into the art world, offering unique insights and behind-the-scenes glimpses into their fascinating journeys.

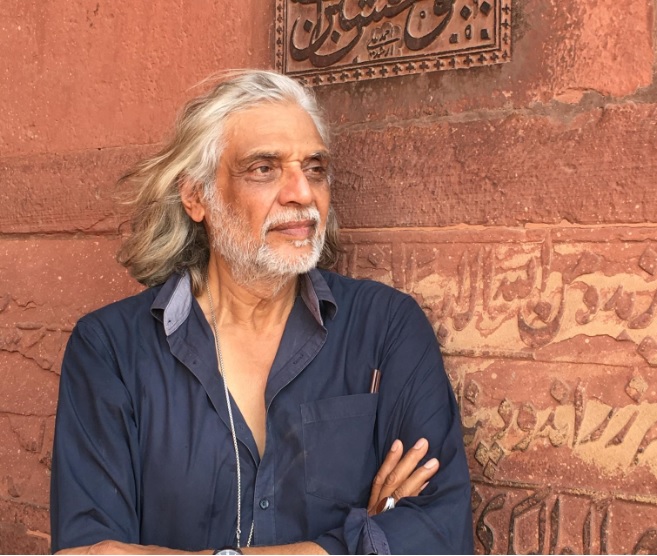

People like Mr. Pinaki Bhattacharjee serve as guiding lights in the dynamic field of architecture, where creativity and functionality, tradition and contemporary, meet. Mr. Bhattacharjee has over twenty years of experience influencing Guwahati’s architectural scene. He is a source of knowledge on the complex interplay among urban growth, cultural legacy, and environmental sustainability. Mr. Nidheesh Tyagi from Abir Pothi will be joining us in this insightful debate. His deep interest in the nexus between art and architecture brings a special viewpoint to our discourse. We explore Mr. Bhattacharya’s insights, viewpoints, and insightful observations on the history, current state, and future of architecture in the area together. Mr. Bhattacharjee’s words offer priceless lessons for aspiring architects, artists, and fans alike, covering everything from the union of history and innovation to the challenges of urbanisation and the requirement of ecological balance. Come along with us as we take a tour of Guwahati’s architectural landscape led by one of its most renowned practitioners, Mr Pinaki Bhattacharjee.

Nidheesh: As an experiential aspect, you know, the way we have this always special experience when we enter a house, how has that changed? I mean, I grew up in Civil Lines, which is like, it could be any city, but Civil Lines will remain the same. People who live in townships or people who live in cantonment areas will have a similar structure. It can be any city, any place. So, as an experiential thing about the space within the house, I mean, moving from the bigger acreage, but then as an interactive space, how do you think it has changed?

PB: Adaptability is something that people are gifted with. So, from a lavish sort of living style to suddenly being confined to a small space may be difficult, but people are fast adapting to it. We never had the concept of having our toilets within the main premises of our house in the olden times; you’d have to walk across a courtyard to reach your washrooms. But now, you have it all within the same unit. So, this is something which has been fast adapted by the generation, even the older generation.

Nidheesh: And how is the functionality and the whole concept of smartness? I mean, I think housing has become so smart in terms of, as you were talking about, people have become flexible, but the houses themselves have also become so functionally smart compared to, I mean, giving it a sense of privacy, the use, and as you were talking about, utility spaces.

PB: Yes, houses have naturally become very smart. We have to accommodate a lot of things in a much smaller space. The space has to be smart enough to be adaptable. So, we have a kitchen which is also a utility washroom. We have dining rooms which can be converted into bedrooms. So, those smart features are there within the design parameters, and we consider them depending on the size of the unit we are expected to design. We also have to keep in mind what our target customer base, what is their affordability. Whether or not they can afford a one crore or two crore flat, if they can afford a 50 lakh rupees flat, even then, we have to give them the same set of requirements, satisfy the same set of requirements, just that the scale is squeezed.

Nidheesh: One thing I was thinking about is that in these tier 2 and tier 3 cities in India, there is a whole big traditional, authentic cultural identity, especially in places like Assam and Guwahati. So, there’s a strong motive and a way people have been, and then there’s the aspiration to become globally compliant in terms of structure. So, how do you balance these two things because both are right for your client?

PB: If we are addressing a housing problem, especially a multi-storied housing problem, perhaps the traditional aspect is less taken care of. Then we look more into the functional aspect, and the cultural and traditional parts are incorporated in projects wherein it has significance in that direction. When it comes to housing, especially multi-storied housing, it’s purely more of a functional project. So, most of the modern buildings that you see around the city are just like other buildings in any part of India. Yes, it’s not unique to Assam; it can be lifted from here and put anywhere in India. It’s just the same.

Nidheesh: But for the bigger houses, what are people’s preferences?

PB: Yes, in those cases, they like all the traditional elements to be incorporated in the maximum way possible while still maintaining their living style. I have dealt with a person who wanted a house of his own in a very traditional ‘missing’ style, wherein the kitchen would be a slightly elevated place where the rest of the people can sit around gossip while the cooking is on. Such preferences are prevalent when there is ample space, and the person is ready to spend on it.

Nidheesh: How much do you think all these, like the huge number of tribes living in this region and their own traditional elements, play a role in the design process? For example, bamboo itself is a massive thing which can be part of the whole design and an element of functionality. So, are these things part of it or have they been completely abandoned, or is there a kind of mix or hybrid arrangement happening?

PB: There are people who are very sensitive, and most architects are sensitive about using bamboo in their architectural practice. However, there are groups who are working extensively in the field, and you will see projects which are evolving mostly with bamboo technology here in this part. It’s a very demanding subject, very interesting, and we need to train ourselves in order to know the true utility and potential of this material.

Nidheesh: What is your process of design, and how do you start from, you know, if you can run us through this whole idea to outcome kind of thing? How do things happen for you?

PB: For most of the projects that I’m handling, it’s the demand of the client that gives direction to the design. We try to accommodate the client’s requirements and also some of their wishes through the design that I think will mostly suit their type of requirement. So, it’s basically a combination of the two, wherein I’ll try to incorporate as much architectural understanding as I have into the project, keeping in mind the client’s requirements. There’s no point in deviating completely from their requirements and trying to force my idea on them because, finally, it is that person who has to feel happy and peaceful living in that space. So, if in the back of their mind, they feel like it’s being imposed on them, I think it would have been better. Until I’m able to convince them, it’s better to keep their ideas intact.

To be continued…