Welcome to Samvaad, where art meets conversation, and inspiration knows no bounds. Here we engage in insightful conversations with eminent personalities from the art fraternity. Through Samvaad, Abir Pothi aims to create a platform for thought-provoking discussions, providing readers with an exclusive glimpse into the creative processes, inspirations, and experiences of these creative individuals. From curating groundbreaking exhibitions to pushing the boundaries of artistic expression, our interviews shed light on the diverse perspectives and contributions of these art luminaries. Samvaad is your ticket to connect with the visionaries who breathe life into the art world, offering unique insights and behind-the-scenes glimpses into their fascinating journeys.

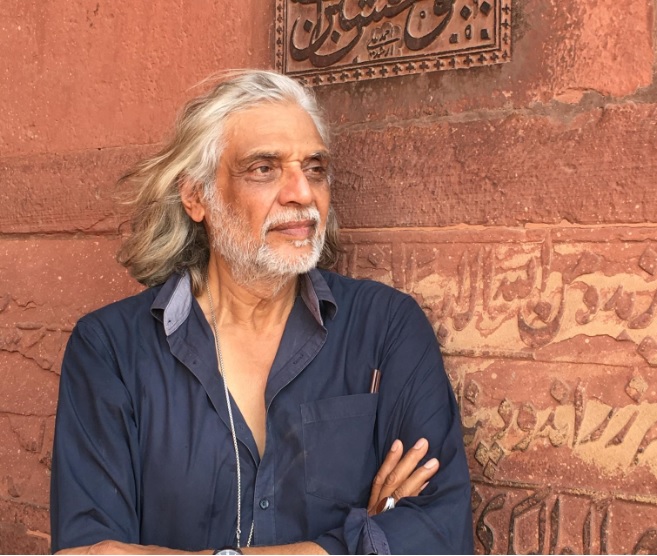

Welcome to another insightful episode of Samvaad at Jaquar, hosted by Ruby Jagrut and brought to you by Abir Pothi. Today, the spotlight shines on a remarkable duo, Sarosh and Azmi Wadia, a married couple whose partnership extends beyond life’s boundaries into the realm of architecture. In this engaging conversation, their journey through the architectural landscape is illuminated, alongside their roles as educators and the intricate interplay between their personal and professional lives. With a rich reservoir of experience and a distinct perspective, Sarosh and Azmi offer profound insights into the evolving facets of architectural practice, the seamless fusion of teaching and real-world application, and the myriad challenges and gratifications of collaborating intimately with one’s spouse. As we delve into the lives and careers of these talented architects, their fervour and commitment to their craft become palpable, enriching our understanding of the narratives that shape our world. Thank you for joining us at Abir Samvaad, where conversations flourish and stories unfold, illuminating the tapestry of human experiences.

Ruby: You are honest enough to confess that, a lot of SEPT people will not confess to it, but we know that’s a reality.

Azmi: Yes, yes, so, and because of that stiffness, we even lost a project. And we didn’t lose it to an architect; we didn’t lose it to an interior designer; we lost it to a model maker. There’s this law in Surat where, you know, you have to leave a margin of, say, 3 meters from the road. In that margin, we had created a raised garden, and there was this entrance portico, the entrance to the house, where we just had a cantilever slab on top. So, when the drawings and all were given to the client’s model maker—this was the time before you had 3Ds, before computers, yes, handmade models—he said, “Okay, fine, give it to him.” So what he did was, he put these huge 1-meter diameter columns in that space, which were totally disproportionate and very ornamental, which didn’t go with the design at all, and arches on the windows. So, we said, “Okay, this doesn’t go, you know, it doesn’t work this way.” And then we got into a discussion and an argument, and things like that. We’re not going to do something…

Ruby: Yes, the model maker took the liberty to change our design, yeah.

Sarosh: Yes, the model maker added various window openings—one triangular, one circular, and all kinds of other windows were there in the model—and the client liked it. So, we said we couldn’t support those changes.

Azmi: So, coming back to it, this is how we learned. Now we are smarter, more flexible—not that we would still allow something like this, but we’ve learned to bargain a little bit. So, okay, we’ll go with a little bit of this, but now in exchange, you know, we feel this will also look better. We find now, as you mature and gain experience, that it’s easier. You know, you can negotiate a little bit, and if they find that you’re open to their suggestions, they will also be more open to your suggestions. So now, you know which fights to pick. Yes, that’s right. Okay.

Ruby: So, especially in architecture, my brother and my family are in the construction business, and my husband is an architect, so I have seen the field very closely. What I realise, or what I understand, is that architects believe that it is their creation. Of course, it’s their creation, but there is a use to it. Let me be polite: they want to leave their mark on the building, to say, “This is my building, my design.” It is often said that architects fall in love with their designs, and there is a distinctive style or mark that we see in the buildings.

Do you think you have something like that? Do you want to leave behind a mark or a style by which you are recognised, or do you keep the project at the center and cater to what it demands and what it needs to serve? What is your take on the style aspect of architecture?

Azmi: I wouldn’t say that there’s a particular style, and I probably wouldn’t want to be recalled for any specific way of projecting my buildings. However, I think I would like to be known as someone who is able to deliver something that is appropriate to the client’s requirements, appropriate to the particular context, and to the specific climate. It’s important that the person or user, the owner, or whoever is using the building or occupying the space around it, is comfortable.

Sarosh: Certainly, we would like to ensure that the building is proportionate and that we leave a mark in terms of the building gelling with the surroundings. It should be harmonious to look at. We don’t want to create something that is, you know, out there—utopian or iconic. We are not Taj Mahal creators.

Ruby: Okay, so, when I’ve been interacting with a lot of architects in the Samvaad series, everyone seems to have a particular philosophy or a starting point when it comes to the process of design. Especially when it is a couple who has studied together, grown together, and practiced together for so many years, I don’t want to ask what your process is, but rather how you start with it, which is a smart way of asking how you do it. Also, who is better at what? There is space planning, service planning, aesthetics, soft furnishings—lots of things and areas to address. Who excels in what, and what kind of fights do you have otherwise?

Azmi: Oh, we have lots of fights. Usually, the space planning is handled to a greater extent by me. Of course, Sarosh has a lot to contribute to that as well.

Ruby: That is, space planning is done by the lady of the house and the lady of the company.

Azmi: Yes, and then a lot of the technicalities, the services, Sarosh is very good at those. He’s very technically sound. So, I don’t really dabble too much in that area because, of course, if I feel that it’s maybe getting in the way, you know, sometimes…

Sarosh: It does get in the way most times, which is why we have our disagreements—severe ones, sometimes. The staff doesn’t know which way to take, so they wait for two days, and then slowly they ask us, “Now, are we supposed to go ahead with the project, or…?”

Azmi: So, they know that eventually, if we don’t come to an agreement, I will say in the office, “Okay, do what sir is saying,” and Sir will say, “Do what ma’am is saying.” You know, so then they know they can’t really do anything. Then, after two or three days, they’ll come up again regarding this issue.

Sarosh: But we had a very brilliant assistant architect who used to work on both the features—what she liked and what I liked—and she knew us very well. Okay, and she would have two alternatives ready the next day. “Can you now just agree on one of them?” So, yeah, thank God we have somebody like that.

Azmi: Sarosh is very particular about the building lasting for a long time. Even if the client says, “I want to go with something else,” or whatever, if he feels it’s not right for the building, he will just not budge. And I think sometimes, if they want it, just give it to them; it’s okay, you know, let’s move on. So those are the tussles that we tend to have.

And talking about falling in love with your design or your project, that’s something we tell our students right from day one: Don’t fall in love with your work because there’s always something you can do better. Don’t think that this is the ultimate, the final that you’re going to do. I remember in SEPT, they used to make us tear up our drawings. We’re not that mean; we don’t do that. But, of course, their drawings are digital, so it doesn’t make much of a difference. But when we were students and were asked to tear up a drawing, it really hurt, yeah.

Ruby: Once, my guru tore a painting that was on handmade paper right in front of me. I was not happy with the composition, and I kept saying that I wasn’t happy with it. He just tore it in front of me. I was like, “What are you doing?” Then he rotated the painting and said, “Why don’t you see it like this?” And it became a new painting. Okay, that is why he’s a guru, and I’m a student, you know. But yeah, I know that it hurts. I was so angry with him to start with. “What are you doing? I don’t like the composition, but it’s my painting. You can’t just turn it off.” But I think I understand what you’re saying, that how to detach from the project is very important.

And I think lately, maybe it is the pressure of competition, maybe the pressure of finishing projects fast, the templates are readily available in the office. Standardisation of building—that this is for the survey area, this is for landscape—and then you will eventually notice all the buildings start looking like each other. So, I think it is very important that one who’s designing the project do that journey every time when he gets the project. And that’s something which I see in your generation very diligently, you know. I see all the senior architects, they say no, it is always a fresh drawing, a new drawing, it’s a new project, it starts with a blank paper. But the younger generation I have seen, they are doing 40, 50, 60 projects at one time. So, how do they manage to do 60 projects at one time? That’s a question I normally ask myself. It’s…

Sarosh: It’s very simple: it’s practice. So it’s simple for the younger generation, but for us, to repeat something we have done, we think twice. We’re charging this client a particular fee for giving something that is exclusive, yes, and then we are actually cheating him by using something which we have already done.