When we think of portraying traumatic events of history through painting, we often wish to communicate it using a visually unsettling image that draws the viewer and does – to whatever degree possible – artistic justice to the event. Beauty, one presumes, bears no immediate relationship to the appalling. For the renowned Indian artist Arpana Caur, part of her artistic journey has been to work against this aesthetic presumption and use beauty to strengthen the force of art to stand against injustice and violence.

Born in 1954 in Delhi, Arpana Caur comes from a Sikh family who fled the Pakistani West Punjab to the Republic of India in 1947 during the partition of British India. Growing up in Punjab in the 50s, her formative years were marked by the fresh wounds of the partition and her grandfather and mother tending to the poor and afflicted with a spirit of piety which became the bedrock from which her creative energies gained sustenance. Caur’s mother, Ajit Kaur, was a renowned Punjabi writer and a figure crucial to her artistic and personal development.

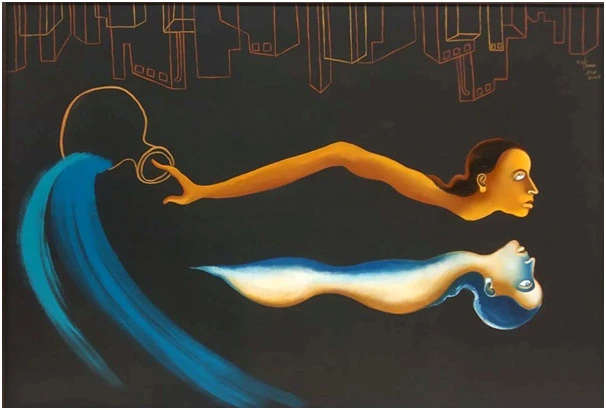

Sohni, 2006. Courtesy of Dhoomimal Gallery Collection.

Sohni, 2006. Courtesy of Dhoomimal Gallery Collection.

Being an iconoclast, her mother didn’t choose her name since in her opinion a name binds one with a religion. She let her daughter choose her own name. At the age of 15, the artist chose the name Arpana. Her first choice was Amrita, after her favourite painter, Amrita Shergill. One of Arpana’s paintings done at the age of 9 is titled Mother and Daughter. Influenced by Shergill’s Hill Women (1935), the work pays homage to the two most important figures in Caur’s life. Caur never received formal training in painting and graduated from the University of Delhi with an MA in literature. She started exhibiting since 1974 not just in the megacities of India but across the world, in galleries in London, Glasgow, Berlin, Amsterdam, Singapore, Munich, New York, and Stockholm.

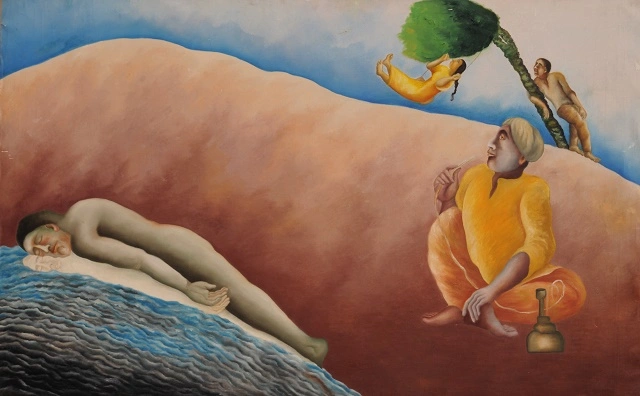

World Goes On, 1984. 5 x 7 ft. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Arpana Caur.

World Goes On, 1984. 5 x 7 ft. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Arpana Caur.

Arpana Caur’s paintings deal with several thematic concerns, one of which includes responding to the events and situations around her. The social issues concerning injustice, human violence and the degrading environment repeatedly draw her to the canvas. After the horrific violence against the Sikhs in 1984 and given her time spent along with her mother in the relief camps, Caur could not stop herself from reacting to the massacre. In her painting titled World Goes On, we see a drowned man lying supine on water while an old man smokes hookah and two figures in the back revel in the moment. What the serene ambience of the painting tries to capture is the moral apathy of the world; that the world goes on despite all barbarity.

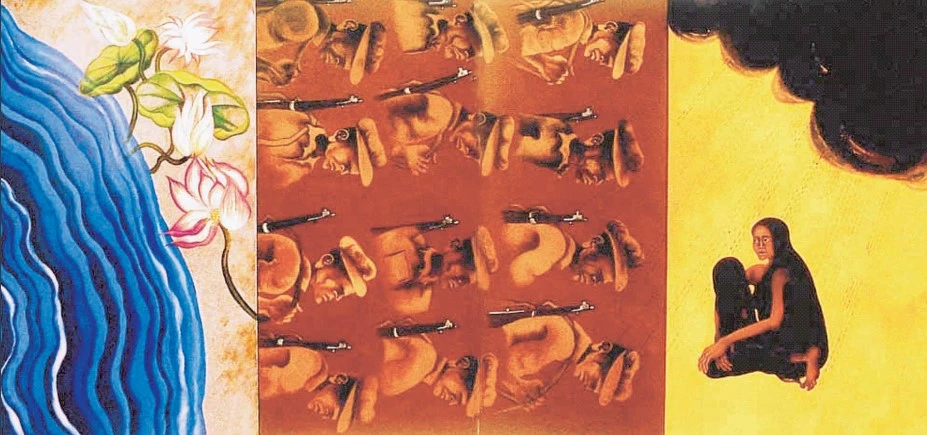

Where are all flowers gone, 1995. Triptych, 70×140 inches, Oil on Canvas. Courtesy of Hiroshima Museum of Modern Art.

Where are all flowers gone, 1995. Triptych, 70×140 inches, Oil on Canvas. Courtesy of Hiroshima Museum of Modern Art.

In 1995, she was commissioned to create works for the Hiroshima Museum of Modern Art to mark the 50th anniversary of the bombings. The triptych, Where are all flowers gone was one of the works she created for the museum. The tender flowers of the pleasing first panel transform into guns while a mother and her daughter lament the aftermath of the tragedy. The female figure is a recurrent feature of her work which has often led to her works and sensibility being termed as feminist. However, she refuses the categorisation and proclaims that her works go beyond gender divisions and address issues that befall humanity in general.

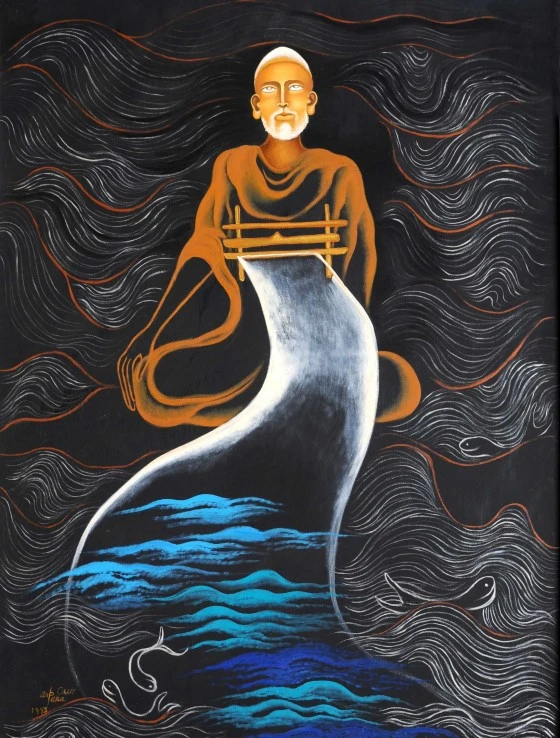

Kabir, 1993. 48 x 72 inches. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Arpana Caur.

Kabir, 1993. 48 x 72 inches. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Arpana Caur.

Mysticism forms another area that has preoccupied Caur since the beginning. Drawing on the traditions of ancient Indian sculptures, miniature paintings, and folk art – her three most important artistic influences – her iconic paintings of Guru Nanak, Kabir, and the Buddha display riveting beings who transformed the world with their teachings. In this surreal painting of Kabir wherein the dark background draws attention to the figure, the weaver weaves a fabric that unfurls from the loom in the form of a river. She says, “In abject poverty, he knew the ‘rasa’ of God to the full. I have shown him weaving water in some works because it douses the fire of religious divisiveness.”

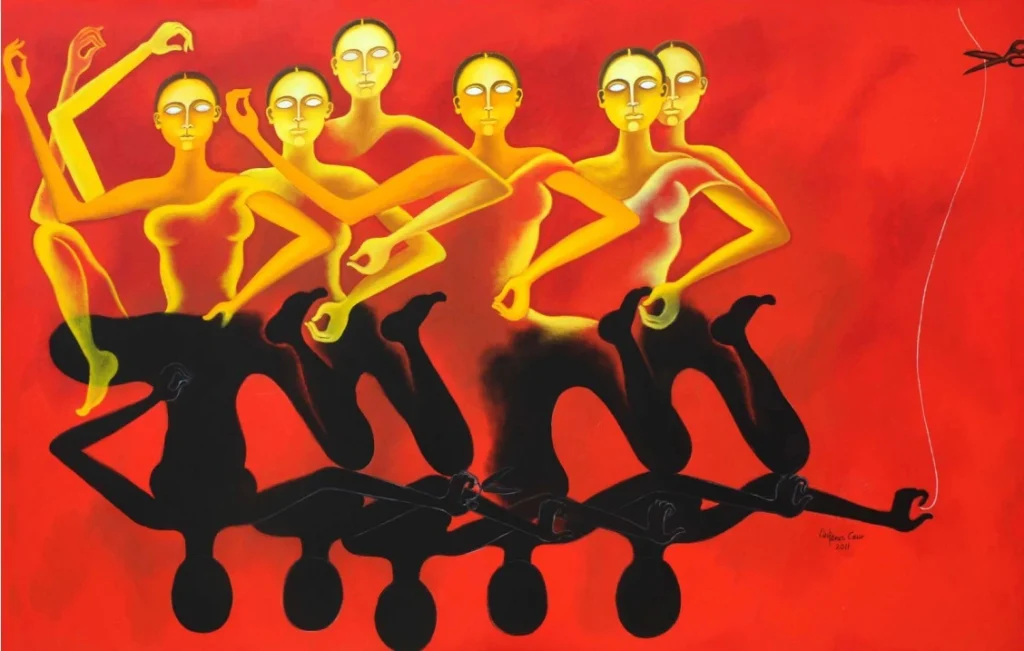

Day and Night, 2011. 102 X 72 inches, Oil on Canvas. Courtesy of Aparna Caur.

Day and Night, 2011. 102 X 72 inches, Oil on Canvas. Courtesy of Aparna Caur.

Time and the related idea of death are other ideas that have been central to her oeuvre. In Day and Night, Caur depicts the everyday cycle of time that has always fascinated her. She had never seen anybody painting the subject. The repetitions in the work slowdown time in its very representation. She wanted time to go slowly in the painting in order to embody the human desire for more time. And yet that never happens. Time flies by cutting all ties, the scissor being an apt and recurrent symbol of it across her work. Satish Gujral called Caur ‘Kainchi’ (scissor) for her use of the symbol which she draws from Greek mythology.

Threat, 1998. 70×84 inches, Oil on Canvas. Courtesy of Aparna Caur.

Threat, 1998. 70×84 inches, Oil on Canvas. Courtesy of Aparna Caur.

Arpana Caur’s Oeuvre extends beyond the confines of this article but what resonates across each one of her works is the idea that no matter how tragic the circumstance, a painting must uplift. While recalling Picasso’s Guernica, Caur certainly refers to the screaming horse, but what catches her fancy and speaks for Picasso’s artistic grandeur is the child holding a flower at the bottom. Even in the darkest of times, there has to be redemption, there has to be art that faces violence with beauty.

References

- Dhoomi Gallery

- iccr.gov- Aparna Caur

- cauraparna.com

Read Also:

Contributor