A New Perspective on AI in Art

Artists should view the rise of AI technology as an opportunity rather than a threat to creativity, asserts the team behind Tate Modern’s new tech-based exhibition, Electric Dreams. Catherine Wood, the museum’s director of exhibitions and programmes, emphasises that the exhibition highlights the longstanding relationship between artists and technology, showcasing that these two worlds have always been and will continue to be intertwined.

Exploring Decades of Artistic Innovation

Opening on 28 November, the Electric Dreams exhibition features over 150 works by 70 artists from around the globe. According to Wood, the museum aims to demonstrate that the conversation about technology and art is not new. “It’s not a new existential threat for creativity. Humans and artists have been grappling with these questions for a long time,” Wood explains. The exhibition provides a historical perspective on the social, existential, and artistic questions surrounding the use of technology in art.

Highlights of the Exhibition

One of the standout pieces in the exhibition is Otto Piene’s Light Room (Jena), where light beams create “sculptures” in a darkened room. This work, among others, exemplifies the innovative use of technology by artists decades ago. The exhibition starts in the 1950s and spans the pre-internet age, reflecting contemporary concerns about technology’s use and control.

Otto Piene, Lightroom with Mönchengladbach Wall, 1963-2013

Cardboard, wood, metal, motor, light| Courtesy: spruethmagers

Art and Technology: A Synergistic Relationship

Wood asserts that art has never been solely about crafting images. “All the artists in the show are grappling with their being, and the technology is a prosthesis or a tool,” she says. This synergy is a central theme of the exhibition.

Pioneers of AI Art

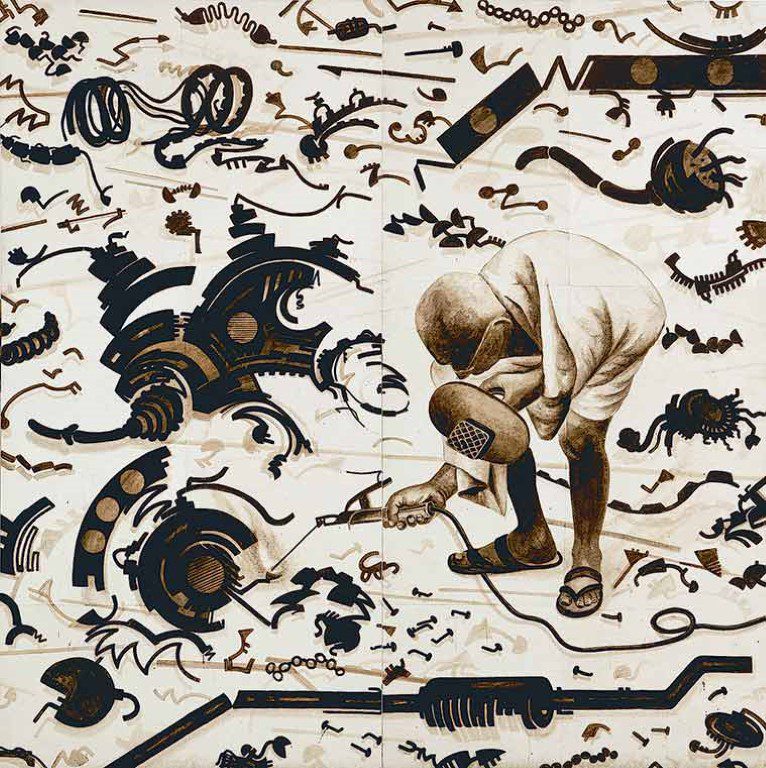

Electric Dreams showcases art that appears surprisingly contemporary, such as Harold Cohen’s paintings created by his “drawing machines” using AARON technology, widely regarded as the first AI technology for making art. Other immersive pieces by artists like Venezuelan Carlos Cruz-Diez and the German duo Monika Fleischmann and Wolfgang Strauss were early forerunners of modern immersive art.

From Gimmicks to Visionaries

Initially, Harold Cohen’s AI-generated art was seen as gimmicky and marginalised. However, Wood believes Cohen was a pioneer and visionary. “From this vantage point, he was a real pioneer and a visionary,” she says. Today, the younger generation, entangled in the digital environment, can look back at these early artists for inspiration.

Historic and Contemporary Approaches

The exhibition also features pieces like Atsuko Tanaka’s Electric Dress from 1956, highlighting how Japanese artists were prepared to take risks and pioneer new styles. “It was partly the technology in Japan but it was also the attitude,” says Wood. The Gutai group, of which Tanaka was a part, made the art-making process a theatrical spectacle, resonating with today’s social media-driven world.

Challenges of Restoring Old Technology

One of the significant challenges in assembling Electric Dreams was getting the old technology to function. Tate’s “time-based media team” worked diligently to revive the hardware, including Cohen’s drawing machines. “They need quite a lot of coaxing,” Wood admits. The team faced the dilemma of preserving the objects versus making them functional and interactive.

The AI and Art Debate

The contentious debate about AI and art continues, with several class-action lawsuits in the US where artists claim AI companies have used their work without permission. This year, Ai Weiwei expressed that art easily replicated by AI is “meaningless.” He speculated that great masters like Picasso or Matisse would struggle to maintain their artistic vision in the AI era.

Conclusion

The Electric Dreams exhibition at Tate Modern provides a comprehensive view of the long-standing relationship between art and technology. It encourages artists to see AI as a tool for creativity rather than a threat, highlighting the ongoing dialogue between human ingenuity and technological advancement.

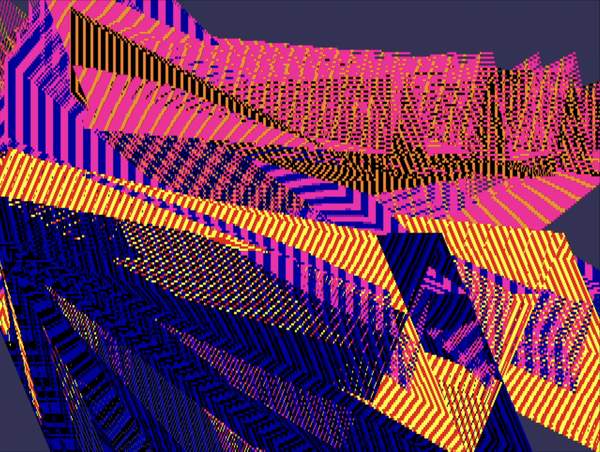

Feature Image: Samia Halaby Fold 2 1988, still from kinetic painting coded on an Amiga computer. Tate © Courtesy the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Beirut / Hamburg