Harlem Renaissance was an intellectual and artistic revival of the Afro-American community, opening African society to a ‘cultured community’ and a more renewed one. Harlem Renaissance brought music, Art, dance, fashion, literature, theatre, political and scholarly mindset, and ambiance to the Afro-American society that communed in Harlem province in the 1920s and 1930s. Harlem Renaissance is provocative and proactive in Art and Philosophy, creating the classical forms of creative expression in the black community in American history for the first time.

Harlem Renaissance carried the civil rights movement and migration of the Afro-American community from different parts of the country to Harlem. Harlem is a destination for the black community and accommodates them. Harlem Renaissance makes black a political idea or entity in many ways and responds to the issues related to Afro-Americans, and blacks generally and black women particularly.

Many black artists, musicians, writers, scholars, political-women activists, performers, and dancers bring together the history of the black community and move towards the revival of the black community. This movement is an incredible history of the Afro-American community in America, giving them education, awareness, a fight against drugs, and finally, the segment of Art and music.

In the Name of Black

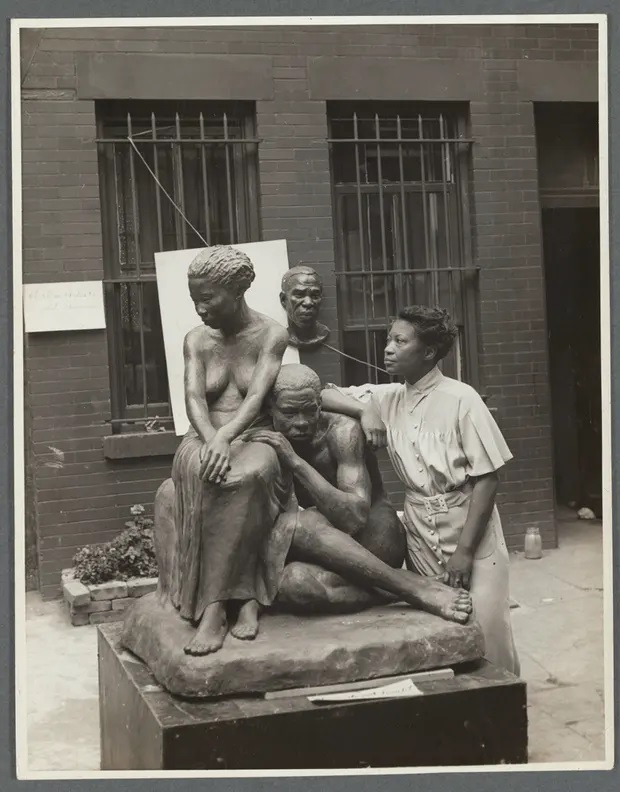

In 1939, one women artist named Augusta Savage opened an Art Gallery, one of the first of that kind in the name of an African Women artist, ‘the Salon of Contemporary Negro Art’, and announced: “We do not ask any special favours as artists because of our race. We only want to present our works and ask you to judge them on their merits.” Augusta Savage was an Afro-American sculptor closely linked with the Harlem Renaissance, one of the leading figures of African revivalists in that period, and a teacher for African people. Her studio is a study centre for African people who wish to change the world themselves and their selves. Before Savage opened her studio under a politically motivated name in 1925, a book titled ‘The New Negro’, edited by Alain Locke, a definitive text and Bible of the Harlem Renaissance, played a crucial role in making it a cultural movement. ‘The New Negro would have to accept this lofty status even as it sought to dispel the prevailing notion among most whites of blacks as not only physically and culturally inferior but without much hope of improvement, writes Arnold Rampersad in the new edition of ‘The New Negro’.

Augusta Savage (1892–1962) overcame the stigma of social settings of Afro-American people, poverty, racism, and coloured and sexual discrimination, and became an influenced and celebrated black women artist in the history of America and in Art. Savage’s artworks praise the Afro-American culture and resistance, catalysing social change that brings from long periods of struggle; many young generation artists, including Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000), Gwendolyn Knight (1913–2005), and Norman Lewis (1901–1979), are influenced by her works and activities.

Through the artwork, Savages carried black aesthetics in a revolutionary style and fashion. Augusta Savages started to do artwork at a young age; even her father did not allow her to do so. She began to make small animal figures in clay that was available locally, and her high school teacher encouraged her to continue her talent and allowed her to teach clay modelling classes at an early age. In a vital event, the 1923 award to Savage of a summer scholarship to study at the Fontainebleau School of Fine Arts in France was revoked by its American jurors once they learned she was Afro-American. But Savage was selected for Cooper Union, a scholarship-based school, when 142 men were on a waiting list, got additional funds for room and board, and completed the four-year degree course in three years.

In the Middle of the Harlem Renaissance

In 1921, Harlem became an unofficial capital of Black America, and Savage moved to Harlem, found a living space, and started sculpting. She struggled to find out to make her living; an Afro- American journalist wrote about her life, “She lives in a poorly lighted room in Upper Harlem, and while putting the finishing touches to a bust she is making”. Savage’s artwork results from her activism and the black American context; the intellectual undercurrent of her Artistic practice reveals to the public presence her work of Art.

Augusta Savages creates a pathway for African artists in America amid many problems, including colour discrimination. Being a women artist was a more risky and challenging decision then. They believed Afro-American artists could have something to do better or unique to give the world more than any other ethnicity. Savage’s artwork engages with people directly, without abstract forms or ambiguity. Portraits of black leaders and subjects are safe in Augusta’s visual language. She often uses black models to do sculpture works that recall the people’s collective memory.

After the creation of Gamin (1929), Augusta Savage became a famous artist in Harlem and the whole of America; many ordinary people claim that they are the model of this iconic work. Gamin, modelled in bronze, depict a street Afro-American boy with an iconic gesture of looking and hat gives Savage at most celebrity status, allowing her to travel to France. A young boy is wise old, looks not starving but knows about hunger and has encountered the world already. Augusta Savage gives a glimpse of the appearance of looking into it and the outer world. All of these options are shown through Savage’s exquisite work. Gamin was, and remains, her most revealing and tantalising work.

Augusta Savages is the point of contact with many movements surrounded by Afro-Americans and other blacks worldwide; the world starts to look at Savage’s Artwork in a way and fashion.

Krispin Joseph PX, a poet and journalist, completed an MFA in art history and visual studies at the University of Hyderabad and an MA in sociology and cultural anthropology from the Central European University, Vienna.