Even a single Samvaad with noted writer, art curator, documentarian and collector Ina Puri is a study in fascinating anecdotes from the modern history and world of Indian art. It is a glimpse into the trajectories of the Who’s Who of the art world, whether it be stunning legends or more recent, exciting contemporary discoveries. The noted biographer, among other plaudits, sits in conversation with Abir Pothi’s Ruby Jagrut, and holds forth on her days in Santiniketan, tribal and folk art, art with a cause, and art in the pandemic.

Let’s start with your early days. You have grown up with littérateur Manish Ghatak, your grandfather…Ritwik Ghatak, Mahashweta Devi… Being in this proximity, as a child, how has it shaped how you are today?

Sometimes you grow up in an environment natural to you — you have known no other life but your childhood has just been that way. I am extremely fortunate to have had such people around and seen them work and interact. My grandfather was a very well-known poet. I was the eldest granddaughter, so I spent a lot of time with him. Mahashweta Devi is Baro-mashi. Whether it is her writing or the way she thought, it is just the way she told stories. In those days, there was not much entertainment for children, so we grew up in the laps of elders listening to stories, looking at them work. We spent a lot of time at my grandparents’ house in Behrampore. All of this shaped and defined the way I grew up surrounded in a Bengali household by listening to music, looking at art, imbibing very informed conversations. Of course these things shaped the way I thought, but it’s just something I was used to. I know no other life.

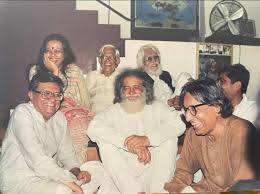

At Manjit Bawa’s exhibition in Ahmedabad with M F Husain, Bhupen Kakar, B D Doshi, Amit Ambalal, Anil Relia and Manjit Bawa

So for you it was a way of life growing up, natural surroundings. At what age did you realize you were ‘fortunate’, if I may ask?

I was precocious and I would ask my grandfather all kinds of questions. He had a vast library and he used to point to books and say, ‘Read this and that will answer your question.’ Somewhere in my head, I realized these were special people. I also had to occupy myself and make myself useful in my own way. I started writing when I was very young. Those days there was Junior Statesman, where I started contributing; later there was Amrita Bazar Patrika. Gradually this thing about writing, expressing myself through words became a natural way of growing up. Initially it was a way to please the elders — you would write something and show it to them, ask does it read alright — but gradually it became a way of life. I still love chronicling things I see around me, whether it is a person, artist, or a filmmaker, apart from my other work as a curator. I love chronicling my everyday, which goes into my Instagram stories.

You were a reader and a writer at a young age, and that comes from your lineage. You have a degree in English literature and you started your early career writing for a newspaper. Were you confused whether you wanted to be a journalist or a writer? What did you want to become?

I studied my Masters at Jadhavpur University and started writing for newspapers. On a family holiday to Bombay, I had the opportunity of meeting Dom Moraes, editor of The Sunday Standard. He was impressed enough to give me an assignment on the spot to do stories for them every week as their Calcutta correspondent. I must have been 21 years old. I did a series on theatre directors, met artists, filmmakers — and that was the beginning. While interviewing them, I would also get to understand their work, see it, visit exhibitions, watch films… It was a process that helped me make up my mind about what I would like to do. In those days, there was no such thing as a curator in India, at least not in Calcutta. But gradually, one thing led to another and so, step by step, I moved towards what I was going to be in my later years.

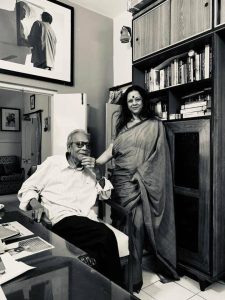

Ina Puri with Nemai Ghosh

When you start observing and absorbing at a young age, it is like a candy shop. You said you were exposed to good movies, music, stories, an amazing lineage. You were growing up in an environment flourishing with a different kind of exposure. When you grabbed the opportunity of being a correspondent and started writing, that experience comes across in profound ways. As you rightly mentioned, in those days, a curator was someone unheard of. When did you do your first curation project, if you can recall for us?

It was a very interesting experience. Those days I had just had our son, who was very young, so I could only work in a very limited way as one wants to spend more time with their child. I worked with an organization called Anamika Kala Sangam, promoting performing arts. That meant going there for three or four hours, when my son was in kindergarten and later when he joined the school. While I was there, although it was performing arts we were working with, inviting groups to come to Kolkata, encouraging local groups to perform for members, alongside I also thought it was important to have an art exhibition. I remember meeting this young sculptor Pradeep Mahanta, who was doing very interesting work. He was from Santiniketan and working with found objects. I am talking about the late Eighties and early Nineties. In those days, it was rare to find someone working with found objects the way he did. I told him let’s think of an exhibition and he was very enthusiastic. He came to Kolkata with his potlas, sculptures and masks, and the things he had created. I put up the exhibition on the lawns of Birla Academy. I guess it was a huge success because half the show was bought off by Bikash Bhattacharya, a very well-known artist. He happened to be visiting and chanced upon our exhibition and said, ‘Oh this is very interesting work’ and bought items. I think I never looked back from there. It was the first of many such adventures and curatorial projects.

In a way, you tried to amalgamate different art forms. You were planning to curate a dance form and then thought, let’s introduce art as well. This amalgamation of two different art forms started a new way of looking at things in the same experience. That’s a wonderful thing to start with in the first curatorial project.

I would like to mention that soon after, I met Ranjavati Sarkar — sadly she is no more — a very young and very gifted dancer at the time. I produced Cassandra, a one-act play choreographed by Ranjavati, and the lights were designed by Naveen Kishore. I look back and that was a unique project that had art, music and performance, and the whole thing was told through music and the story of Cassandra. I have always tried to include these projects in my own journey, not to be focused on just showing art as art, but to show other forms of art alongside whenever possible.

Perhaps that’s how you enhance and create your own vocabulary. That is how we enhance the experience of people visiting the exhibition. It is more than different senses engaging — dance and music is ‘asthayi bhaav’, but paintings and sculptures are ‘sthayi bhaav’ of art. The amalgamation of these two different bhaav is also a wonderful experience for the people experiencing that exhibition. It is rare these days; it is not happening that way often, but it should. It is something we should take note of from people like you, who started very early in their career. Now when we see curatorial projects, it is like they are frozen in one form of art, whether sthayi bhaav or asthayi bhaav.

Moving on to your curatorial projects — I would like to ask if it was a conscious effort to bridge the gap between artist and the common man, between artisan and a viewer, to try to create a different vocabulary?

Let me tell you about the most recent project. This is a series I curated with Jayasri Burman and it was standing for the last two weeks at Bikaner House. It was a unique project, where the entire series was dedicated to the Ganga. She had made paintings, sculptures, sketches. The idea was that you invite people, which we did, but also to open it out to students, anyone interested to come in and see, to ask questions, to ask the artist and interact with them. It is a very vital ingredient, where we have to leave these channels open, whereby you can talk to people, not make it exclusive, not make it elitist, but just to open the doors and let people walk in.

There are a lot of young artists who otherwise feel you are inaccessible or one cannot meet Jayasri Burman and Ina Puri — they should have grabbed the opportunity. In the earlier ages, when I was learning from my Guru, he said mentorship is a must, handholding is a must. We also used to go to our Guru’s home and wash ‘bartan’ at his place. Times have changed and these kind of programmes are rare but when you open doors for young artists, and viewers, learning can happen and, I hope lot of people have taken advantage of your initiative where you say let’s have a dialogue. Do you think people were intrigued by the idea where they wanted to know more? Have you experienced an instance when someone has come to you and asked: ‘Ina, tell me about this work’?

Many times. I had Manjit Bawa’s exhibition at the Academy of Fine Arts; that was pretty rare because he had only exhibited at private galleries before. When I met him and started working with him, I told him let us do this at the Academy in Kolkata for a lot of viewers — not only collectors will come, but everyone will, including young people and enthusiasts. I was proven right because people streamed in and asked him questions, about colours, the flat background. We are argumentative Bengalis and indulge in these exchanges. I think it is so important, if possible, to be present. To take questions, to answer questions. That is the way I have always worked.

Speaking of young artists, I would like to mention a young artist I met, who was experimenting with different forms and media at the time. His name is Narayan Chandra Sinha. He lived in Nalhati, a two-hour journey from Santiniketan, and I heard about him from some people in Kolkata and I made this journey to meet him. Can you imagine from Gurgaon to Kolkata, from Kolkata to Santiniketan, to Nalhati! The journey was the right thing to do, I realize in retrospect. I am glad I went and saw his studio and his work and I was extremely impressed with the way this boy was working. He was in his twenties then. Today, Narayan is an established name. I did Debi, an exhibition, and when it came to Delhi, people raved about it. It was a huge success. Recently, he has done an exhibition called Fire and Light, which is a sight-specific show. I talk about mentorship that has gone on for the past 10-11 years and it is important to you because you learn. There is a young gallerist I have worked with recently, his name is Somak Mitra, and he is 27. His gallery has put up this exhibition and he says ‘Inaji, you are a mentor’! I like to work with young people and see how they work, how they think — because they dream big, they are audacious, young and unfettered. It is a two-way traffic.

Being a witness, being there to help them grow also feels amazing. I hope a lot of people take advantage of you being around. You are also a big art collector and keep identifying good art for yourself to collect. What are the features in artworks that you feel drawn to? You have worked with Manjit — he has a very minimalistic, very simple way of manifesting his work. You also talk about working with someone who works with found objects, which might be very different, very crowded. How is the process? Does it change over time?

At different periods of time, I have responded to different artists. When one starts collecting, it isn’t about money, but inclination, interest, finding something you love and wanting to collect it and look around more. At Santiniketan, I picked up the beautiful platters by KG Subramanyan and Jogen Chowdhury. In those days they were around Rs 1,500-2,000 — today they are worth huge money. But I collected because I loved collecting and I have never sold a single work from my collection. I remember when I was married, the money I got in gifts was all carefully saved to buy a Jamini Roy painting. One is young and idealistic. I bought Zarina Hashmi’s work much later as I responded to her work much later in life. I bought Himmat Shah’s sculptures, paintings, sketches. In different periods, sculpture appealed to me. Photography is a new love I discovered 10-15 years ago. I met Nemai Ghosh, with whom I have done his last big book of photography; the other book I did with him was The Faces of Indian Art. During its making, I bought some of his works. There is of course, Raghu Rai, with whom I have had two books. I am privileged that he actually gifted me a portrait of mine when we were working together in Benaras. When you work with artists, you sometimes get these beautiful tokens of appreciation. There are so many different ways in which I have collected these works that hang on my wall. Tomorrow, I might decide I will go for something white on white, or completely minimalistic — who knows. At one point, colour appealed to me. Manjit was a master of colours, those gorgeous yellows… I am still fortunate in having a fabulous collection of his work that I love. But equally I think, there is also work by Rabin Mondal, Jogen Chowdhury, Manu Parekh, Madhavi Parekh, Manisha Parekh, Ranbir Kaleka… These are the people I love and they are part of my home and my life. My son has taken to collecting. My granddaughter came to Jayasree’s exhibition and came home and identified her work saying, ‘That is Jaya mashi’s work!’ I think my art is in good hands.

You keep mentioning Santiniketan. Can you elaborate on your relationship with Santiniketan as it is in your thoughts?

Santiniketan was important. The whole environment, meeting artists, going to the studios of Jogen Chowdhury, Sanat Kar, Rabin Mondal… My parents had a home there, so we visited very regularly. The whole association with Santiniketan started very young. We used to go during a mela because the art was not very expensive, and there were all these young artists, like Mithu Sen, emerging as powerful voices against the backdrop of Santiniketan. There was the opportunity to see these young people and their work alongside their gurus. For example, KG Subramanyan had a home there and we knew them as our parents’ friends, so we were allowed to go there and look at the work and mess around in the studio. We were lucky. Later in Baroda and elsewhere, where he moved, for his 90th birthday, I was fortunate as I made a Doordarshan film on him. Goutam Ghose was there and the movie was a remarkable celebration of a man in his 90th year, who was still working. So yes, I had a personal association with artists based in Santiniketan.

It appears as a dream childhood and upbringing, if you have an inclination towards art and you were just there, being part of that journey. Another name you mention, of course, is Manjit Bawa. You have written about him, made a film on him — what kind of a person was he, what was his philosophy? What was your experience directing his film and working with him?

It was remarkable. I first met him in the mid-90s when I was taking a show to Singapore. Alongside all the senior artists I had met, I just thought it would be wonderful to include Manjit Bawa. At that time, I was in Kolkata and I came to Delhi. I had the opportunity to meet him and see him work. I was hugely influenced by him. Even today, when I look at a painting I hear his voice, saying, ‘This is the way that you look at this work, just look at the colour that he has used, the palette, or the texture, or the forms.’ He was someone who was very generous when it came to praising artists and when we became friends, he used to take me to exhibitions of young artists in the capital. Manjit was a visionary, a philosopher, a thinker, a brilliant musician, but most of all, he was a very loyal friend. His friendship with people, young artists, continued till the day he passed away. That is his biggest quality — that he could befriend people so warmly, so generously, and he could share his knowledge, his wisdom. People would come to him and he wouldn’t say ‘buy my work’, he would say, ‘Arre usk kaam dekha, Ranbir Kaleka ka kaam dekho, bahot badhiya; Arpita Singh, I love Arpita’s works; Jayasree Chakraborty ka kaam dekho, iska kaam dekho.’ And that is really big, because a lot of successful artists tend to talk about themselves and only themselves. Manjit was so different that in today’s day, I find that quality completely unique to him. It is wonderful that he could look apart and away from his work and talk about other artists. He would talk about Avni Sen, his teacher in school, about the first animal forms he first learnt to draw in this classroom. Sailoz Mookherjea would speak of him very fondly, too. W went to Santiniketan together and were shooting Faces of Indian Art, at which time he went and met Somnath Hore, who was also a professor in art college with him. Being with him was also like being guided to look at art and artists’ works in a totally different way.

I came across this beautiful book by the Rumi Foundation on Sufis of Punjab — in there, they have a chapter on Manjit. I was amazed reading about his Dalhousie days, how he moved out of Delhi and how he was disheartened after it. You have said generous and philosophical, but since I read that book, Sufi is one word we missed out. He was a true fakir from within. I was amazed at this sensitivity towards the environment. We have become a little thick-skinned lately and we are ok with lot of news around us — but Manjit was a sensitive soul and is rightfully there in the book of Sufis of Punjab. That is how one should know him. People like us were not fortunate enough to meet him personally, but if we have to know him, we have to know he was a true Sufi and would think from his heart. He was very generous as a human being.

He lived the life of a Sufi. He was not a philosopher, but it was the way he lived, the way he thought. In Dalhousie, he would start his day very early working on miniature paintings and after that he move on to larger canvasses and through the day he was painting and working — but in the evening he would gather people and the staff, any other person passing by, and say, ‘Chalo.’ And in the winter evenings there would be a big fire going on and he would sit with his dholak and they would all sing. So his whole life was like that of a Sufi. Which is why when Buddhadeb Dasgupta directed the film, Meeting Manjit, which I had produced, most of it was shot in Dalhousie, because he was most at home there. He loved animals; he would be passionately fond of them. When he would leave for Dalhousie, the drive from Delhi to Dalhousie is about 10-12 hours, but if he found an animal in distress, he would try and stop, if a car had hit a cow, he would just reach out. That was his nature, how he was.

A true Sufi. In his work as well, we come across that serenity and godliness. It is wonderful to hear about him from you and we have seen those films because we are fans and have watched them on some platforms where we could see it free of cost. That is how we have understood Manjit, and it is your contribution to the next generation. I think these books play a pivotal role to understand his art and him as a person. It is important for all young artists to read and understand and know somebody.

You are also closely associated with Kolkata Centre for Creativity (KCC). Can you tell us about that?

In 2006, this is immediately after Manjit went into the hospital, he was in a coma for three years and 17 days. After that, KCC got in touch with me. I had known them since my Anamika Kala Sangam days. They wanted to buy art and approached me. One was you were going through a huge depression because a very dear friend was lying in coma, we had no idea what would happen — and at that point they asked me to start looking at art. At that moment, I started reaching out to artists again, this time to collect for an organization. That is how it began and my association continues till date. In the middle, I couldn’t give them much time, but recently we are talking about hosting a lot of shows about Shahidul Alam, and a retrospective of a very senior Bengal artist; and there are several projects that we would like to take up. They are doing very good work. They have a team of curators and young artists on board. Richa Agarwal is doing brilliant work and she has my complete support in what she does because the way she is bringing the organization forward impresses me. Today Mr. Agarwal is not well, so it is Richa who is holding the reins and is doing a brilliant job.

I think with you around, KCC will have many more events in the future. Another thing I would like to ask is about your work with tribal art.

I just think that when we talk about art, tribal art is also art. Like in Kolkata we did an exhibition called Spirit of India which included some brilliant artists, with exquisite works. It took place just before the pandemic and was a huge success. Personally, I would not like to slot the genre into abstract or figurative or installations, but just call it an art exhibition.

In Bhopal, Manjit had actually showed me the work of some brilliant (tribal) artists, like Bhuri Bai, Durga Bai, and Pema Fatiya. By the time they set up their museum, Manjit was gone. I have continued to visit Bhopal, and had exhibitions with Venkat Shyam for instance, and recommended him for shows in Singapore and elsewhere. So, they are all very much on the radar. Whenever I get an opportunity, I certainly tell my friends to collect their art, and would love to work with them again and again.

There is a certain awareness we generate in the next generation when we include these art forms. We are now entering a very dangerous era of digital and virtual reality, where if you do not give this exposure around tribal craft or folk art to the younger generation, it may be too late to preserve it. It is important for them to be in sync with this lineage and heritage, too. Curators like you being aware of this and trying to keep it inclusive is a great service to society, not just the field of art — we need to have somebody reminding us to look here and pay attention to what we will lose otherwise.

Iconic figures like Laila Tyabji have been working tirelessly for this and I would give them full credit. We are merely on the periphery doing shows as individuals, but they have set up things like Dastkar and these organizations that do brilliant work; or look at the way art is promoted at Dilli Haat.

Including tribal and folk art in a contemporary scenario, such as say a young contemporary artist taking some older art form and expressing it in a very noveau way — I would like to see such experimental projects as well and more frequently. We are all learning from each other and this exchange of ideas and knowledge and skills should happen more often.

I remember Manjit had worked on one such project with Bhuri Bai… We should certainly think of having more such collaborations. You said something about a new era being upon us now, of virtual art? I would say this is just progress, the way things move forward. That will also become a part of our art world, and that is perhaps the way we will function in years to come.

We will adapt and grow… but do you think we have become less patient or persuasive? We, especially the next generation, will have to strike the right balance, and be conscious of the self while venturing into a new normal, be one’s own yardstick!

You have also initiated some very successful fundraisers. We spoke of blending art and folk craft, and now let us touch upon blending art and the social cause, to learn about that part of your graph.

I decided some years ago that I will, once a year, do a fundraiser and work on it for two months, to do something worthwhile. The idea is not to make money or see it as a commercial venture, but just to be able to give back and do something for society at large.

There have been various programmes I have been involved in, over the last few years. But, when Cyclone Amphan hit, it was very close to home, in my home state, in Kolkata, in the Sundarbans. Homes and livelihoods were destroyed, people killed. It was utter devastation. I felt we had to do something and reached out to artist friends across the board. Everyone came forward. Most simply donated their works, or took a 15-20% fee. With the help of the platforms set up by KCC (Kolkata Centre for Creativity) and Shalini Passi Art Foundation, we were able to reach out to people across the world and everyone gave generously. The entire money we raised was sent to the Ramakrishna Mission, who we decided was doing great work and could take our effort ahead on ground.

When it comes to a social cause, every small step counts. We have heard a lot about your effort and contribution. There was also an innovative colouring book, conceptualised and published during the pandemic by you. How would you feel the pandemic has changed us, art and you as a person? How have the last two years affected you?

In the beginning of this year, I had Covid myself. We have all lost friends and family to the virus. It has indeed been a dark and depressing time. But what mattered also was keeping our heads up and staying as positive as possible, to try and make some sense out of this crazy time we are living in.

I wanted to make use of our energies in a positive way. It was a time when we were spending a lot of time at home, and so I thought, let’s put together a book on the ‘magic of colouring’. I asked some artists to help me with their works. The book is for children and adults, but has contributions from some senior artists like Sakti Burman, Paresh Maity, Jatin Das, Subhaprasanna Bhattacharjee… So many people came forward and did these beautiful outlines for the book. The response has been fantastic, and we are selling it at a nominal price through KCC. Now that we are more at home, it is a very soothing pastime to fill out the outlines, whether with watercolours or pastels or crayons. Your mind works in a positive way and for those few hours, you are in a happy space.

What feels like a small gesture has helped a lot of people, as a constructive use of energy and time. During the pandemic, Lalu Prasad Shaw’s exhibit also got cancelled…

I hate to use the word cancelled, postponed is better! Lalu da’s retrospective is slated for later this year, and the text and exhibit are both ready, soon to be displayed at Bikaner House. A retrospective of Rokeya Sultana from Bangladesh also got postponed to February. These were the two major shows that were affected. But, there has been a lot of positive work as well — such as Bharti Kher exhibiting right now. Many artists like her were able to work through the pandemic and showcase their creations now, because they were able to spend time in their studios.

Last year, when Nemai da (Nemai Ghosh) was unwell, Paresh Maity and I were doing a project with him, a book — but by the time we sent home the very first copy, he had already left us. I do regret that the pandemic caused delays. It was all different, the book was launched virtually. But sadly, such an important part of it was no longer with us.

What words of advice would you impart to a young foundation like Abir, to young artists/curators/galleries?

We have to gather knowledge, no matter how old or young. One can always continue the process of learning. We should never be in a place where we feel like we know it all. Always keep your eyes and minds open, visit shows and read up even if you can’t attend something due to the pandemic. Some of the most interesting people I have met have been because I had the patience to look at their work, visit their exhibitions and just make time for them. If not, I would have lost out on some amazing projects. I hope that never happens and that I always have the time to look at art and meet young curators. Ideally this happens in situations like Serendipity in Goa, for instance, or India Art Fair or the Kochi Biennale. These are places where you meet young people with dreams. Not everyone can reach the heights of a Subodh Gupta or Jitish Kallat. But many want to be like them and it is important to encourage them, it is important to make a space for them in your works and exhibitions. To be inclusive — that is the mantra.

In this changing time and scenario, not everyone has access. At the foundation, we have a young farmer’s son, who has studied to be a painter but does not know where to go, hailing from Saraf Ali in West Bengal; one of our winners of the search this year hails from Lalgola, also in WB, which is quite unheard of. So, how do we bridge this gap, as a society, between young bright artists and their wish to become the next Subodh Gupta?

Well Subodh himself comes from Bihar, and he has also not had it easy, and has had to struggle a lot before achieving this kind of success. Narayan Chandra Sinha hails from Nalhati, which many may not have heard of. Senior artist Thota Vaikuntham hails from a place in Telangana where there were not many artists around as he emerged. They have all had to struggle very hard. There is no easy solution to this. It just involves a lot of planning and work and industry. You just have to put it all together and continue working. People just think ‘I want to be a Raghu Rai’ and work like him, but you have to have your own narrative! Take another iconic figure like the brilliant photographer Dayanita Singh, whose footsteps any young woman may want to follow in. Certainly look at her work, read about her — but then, create your own language and don’t copy her or the way she works. It is important to be original.

That is the take away from Ina Puri. Be original, and nobody has it easy — that is what we need to imbibe. We all have to find our own path, and collect the wisdom of people on our journey, our dream. Follow your heart. Thank you, Ina Puri, for your time and generosity!