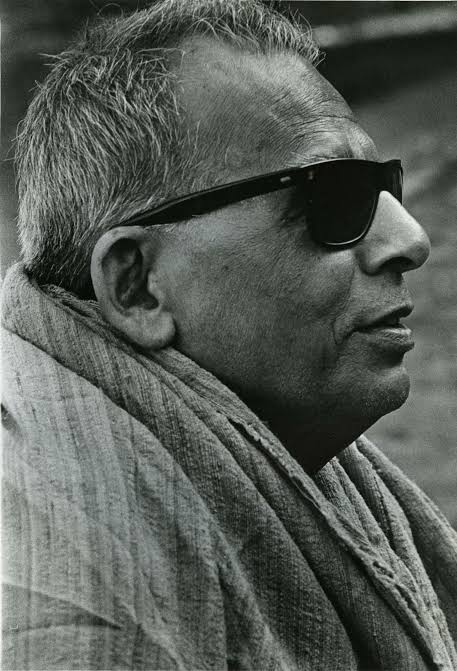

Born in 1904, Benodebehari Mukherjee had severe myopia in one eye and was completely blind in the other. At age 53, he completely lost his vision. Mukherjee, a painter of landscapes and frescoes, passed away in 1980 after producing ground-breaking works. In the 20th century, he came to define contemporary art in India as a sculptor and muralist. The scroll, which is only six inches broad, will be sent in July to Santiniketan, the West Bengali university town established a century ago by Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore, where Mukherjee studied and subsequently taught.

A 44-foot-long Japanese-style handscroll painted by a well-known Indian blind artist about 100 years ago has emerged and is now on show in Kolkata, the city of his birth, for the first time. Scenes from Santiniketan is the title of the artist’s longest scroll. Before arriving at its ultimate location in Kolkata, where it is presently on display, the scroll was transferred into two different hands.

It appears that in 1929, Mukherjee either gave the scroll to Sudhir Khastagir, a Shantiniketan art school graduate, or sold it to him. Khastagir eventually relocated to Dehra Dun to work as an art instructor at a prestigious institution. He gave the scroll to another artist, who later sold it for an unknown sum to Rakesh Saini, an archivist and proprietor of an art gallery in Kolkata, six years ago.

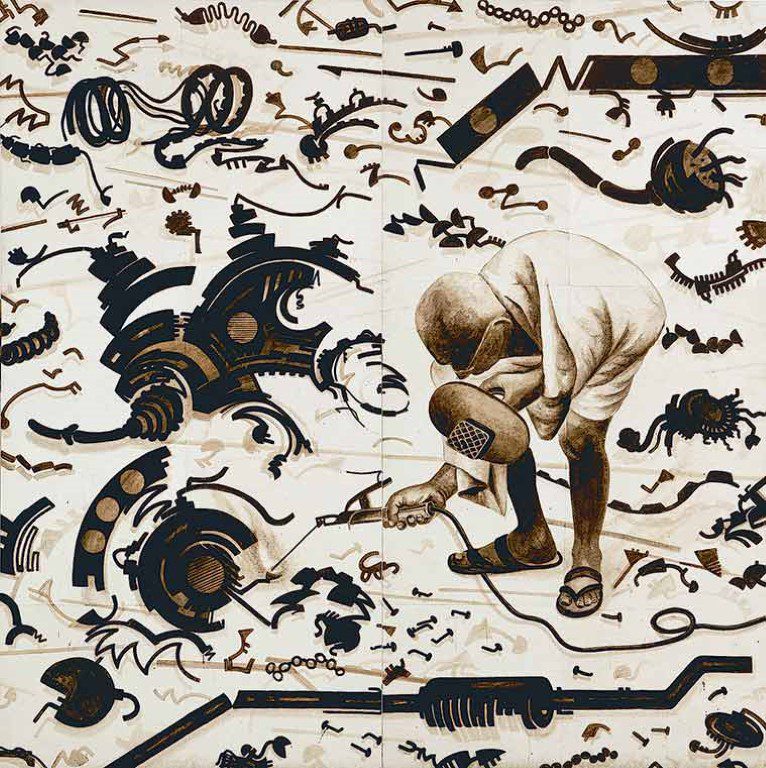

Mukherjee created this intriguing scroll at the age of 20 using ink and watercolors on painstakingly arranged pieces of paper. The artist who leads the visitor on a tour of Santiniketan in the first frame is depicted as a person sitting beneath a tree. This is a common pattern in Chinese and Japanese scrolls where carefully positioned images direct our gaze.

There are 22 human figurines, 22 cattle, 3 poultry, 1 dog, and 1 bird on the scroll. Mukherjee employs expanses of nothingness to represent the earth and the sky.

The scroll is characterized by the artist’s “solitude, a sense of isolation subtly expressed and presented…as a state of his life, without self-pity or bitterness,” according to Siva Kumar, a renowned art historian. He claims that the scroll “bears all signs of the artist’s genius that flowered in the coming years”. The representation of the khoai, which was painted in the middle of the 1930s and is slightly over 10 feet long, was Mukherjee’s largest piece until it was discovered.

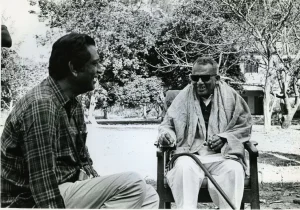

One of India’s renowned painters, Nandalal Bose, who oversaw the art school Kala Bhavan, was Guru to Mukherjee in Santiniketan. According to Siva Kumar, Bose had voiced worry to Tagore over a visually handicapped art student. “Is he sincere?” Tagore answered. “Is he enthusiastic? So leave him alone.”

Mukherjee’s Kala Bhavan pupils were almost as well-known as his teachers. Artists like KG Subramanyan, Somnath Hore, and Oscar-winning director Satyajit Ray were among them. The Inner Eye, a film by Ray about Mukherjee, was produced in 1972. The heartfelt homage thrust the solitary artist and his creations onto the world scene. Prints of handscrolls that Tagore and Bose had brought back from their trip to Japan may have served as an inspiration for Mukherjee.

Courtesy: BBC

“Mukherjee was specifically interested in the format of the scroll, an art form that has certain possibilities which other forms don’t have like [showing] the passage of time,” says Siva Kumar. “You can recreate the experience of walking through a landscape rather than just standing somewhere and looking at it. In normal landscapes, you fragment nature. But in a handscroll you can show continuity and transformation.”

Where then did the Scenes go missing for almost a century?

The scroll was purchased from a collector by Rakesh Sahni, the proprietor of Gallery Rasa in Kolkata, in 2017. Mr. Sahni claims, “I could have displayed it earlier, but I lost three years to the pandemic.”

Courtesy: BBC

Reproductions of Mukherjee’s other scrolls, such as The Khoai, Village Scenes, and Scenes in Jungle, are also on display during the Kolkata exhibition. The Victoria & Albert Museum in London is the owner of the final piece, which is painted on the semicircular pith of a banana tree.

The frescoes on the walls and ceilings of the buildings in and surrounding Kala Bhavan are among Mukherjee’s other well-known creations at Santiniketan. The Lives of Mediaeval Saints on the walls of Cheena Bhavan, a Sino-Indian cultural studies institution, are among the most well-known and stand at about eight feet tall and an impressive 80 feet in length. Before the artist lost his vision, he completed the frescos and scrolls. Mukherjee continued to produce murals, collages, and sculpture to the end with the same artistic skill as the works he had produced when he could still see with that one eye, even after surgery removed his functioning myopic eye.

Mukherjee makes a rare mention about his visual impairment in Ray’s documentary: “Blindness is a new feeling, a new experience, a new state of being.”

Source: BBC

feature image courtesy: BBC

Pratiksha Shome

Pratiksha is an art enthusiast and writer.