Pratiksha Shome

The title of this show at the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art in Cape Town is a parody of Ava Duvernay’s 2019 Netflix film “When They See Us,” which centres on the Central Park Five, a group of Black teens who were wrongfully charged with killing a white jogger in 1989 before being cleared 13 years later. The term “When We See Us,” which the curators Koyo Kouoh and Tandazani Dhlakama have reversed, represents an effort to remove the unfavourable prejudice with which Black life is perceived, written about, and spoken of. The exhibition explores how Blackness and Africanness have been represented through 200 paintings created by 156 Black African and diasporic artists, whose works date from the early 20th century through the year 2022.

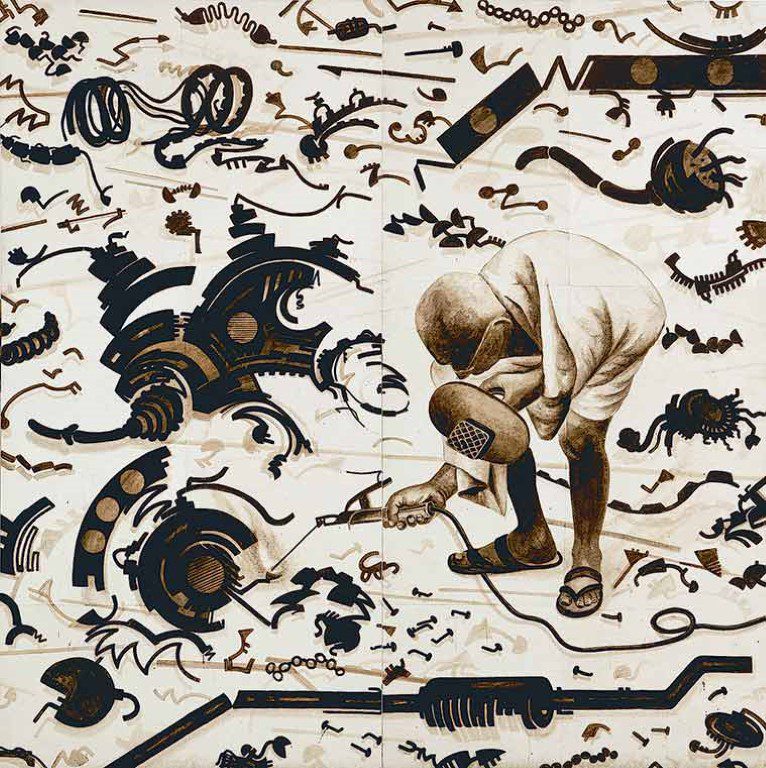

The figures in these paintings are immensely diverse when seen as a whole: they include lovers, healers, heroes, villains, and mythical beings who participate in worship and dance, running and combat, as well as reading, relaxing, sleeping, and reflecting. Overall, the show’s structure conveys a sense of optimism earned via pride and self-awareness. The majority of the show focuses on Black joy in particular. Examples include Joy Labinjo’s (2018) Gisting in the Kitchen and Moke’s 1983 Kin oyé ou Coulier Madiokoko à Matonga, both of which show a group of men and women dancing in a club lit by dim, rainbow lights.

Contemporary artworks portraying characters with exaggeratedly black, even jet-black skin are also prominently featured in the exhibition. Examples include Kwesi Botchway’s Green Earflip Cap (2020), Zandile Tshabalala’s Conversation (2020), Amoako Boafo’s Teju (2019), and Cinga Samson’s Ibhungane 16 (2020). Two women with shaven heads are depicted in Tshabalala’s Two Reclining Women, a startling standout with bright-red lipstick and leopard print nightgowns that jump off the canvas.

Problems arise from both the excessive optimism and the emphasis on skin tone. The positive tone of the show raises questions about its potential in light of the ongoing global anti-Blackness. Dhlakama cites author Kevin Quashie in her catalogue piece, who bemoans the fact that “nearly all of what has been written about Blackness assumes that Black culture is, or should be, identified by resistant expressiveness—a response to racial oppression.” Nevertheless, she claims that the display was designed to challenge the pervasive attitude of exploitation and persecution. It’s a reasonable impulse, but occasionally it comes out as forced, as if there’s a need to affirm something about being Black or African.

It can be said that Kerry James Marshall and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye are to blame for the exaggeratedly black skin tone, but it’s not apparent what the next generation is doing to develop or complicate the method. And it’s crucial to do so because its pervasiveness can contribute to stereotypes of simple visibility and representation without always posing a threat to how the Black body is perceived. Artists run the risk of portraying the Black body as a gimmick when they make such a strong connection between Black life and Black skin.

Source: Art in America