Krispin Joseph PX

Photography reads as a subject of historical context. As a topic, photos are the immediate reference for historical readings; photographs turn history into a visual experience, a framed visual field of history. When photography starts to document history, we read photographs as an agency for reading history. West Bengal-based visual artist Dipanwita Saha’s ‘‘Trail Of Blood” displayed in ”Communities of Choice”, a collaborative show by Chennai Photo Biennale Foundation, India, and Ffotogallery (Wales), at the Kochi Muziris Biennale, supported by the India-UK Together Season of Culture Program, uses photography as a medium for representing historicity of communal violence.

In this project, Saha visually demonstrates the verbal memory and history of the violent past still in the veins of people’s lives, and that still haunts them. The artist discusses people from Culcutta carrying the unforgettable past in their memory, knowingly or unknowingly, which became part of their life and remembrance. The Saha focused on the ordinary people’s oral narration, which remains unheard, instead of the prominent players of communal violence, which led to a massacre of more than 4000 people causing the Great Calcutta Killings.

The artist says the communal violence segregates city life into two layers, people living in a marginal hatred between the communities. This segregation and the hatred napping in city life is only visible in an inter-religion marriage, and renting a house becomes a subject. The visual practice of the artist is deeply involved in these subjects to understand the polarization of Indian society based on religion. These issues divide the country, rooted in today’s concerns of the burning problems of NRC, violence in Delhi, Chanda Nagar, and increasing tensions in Assam reflect the same problem. This visual documentation follows the direct victims of communal violence; they live in painful memory of the violence that fumed everything forever.

Dipanwita Saha witnessed the Delhi riots in 2020 and learned the similarities between the two incidents of violence, which realised and led her to this project. What made communal violence in 1946, the same thing going in the Nation’s veins in the name of NRC, the government is trying to segregate the nation again, which is against India’s cultural and constitutional identity. This silence and speech, memory and forgetting, pain and healing echo this reality repetitively.

Artists create a visual journey through the collective memory of the city and its residents that bridge between communal violence tendencies in the past and present in our greatest pluralist country.

Blood in people’s memory

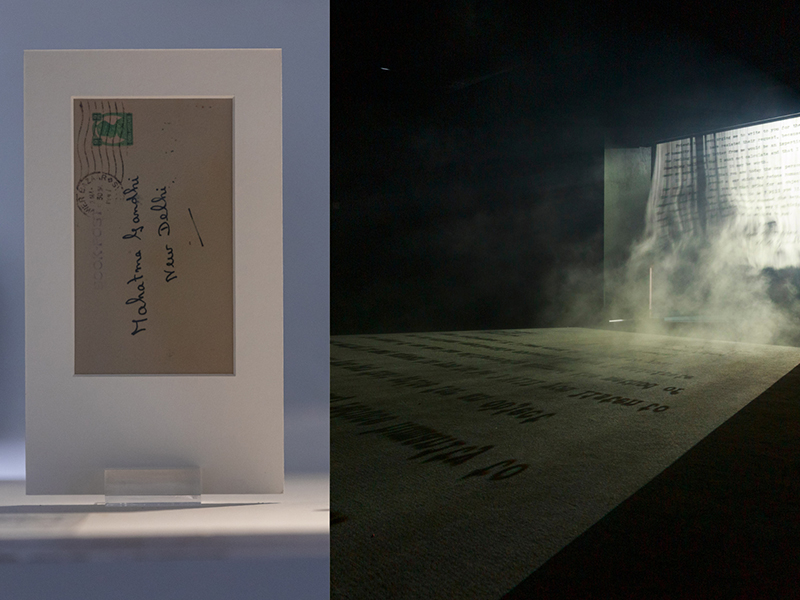

Blood comes from people’s pain and memory; the artist replied to a question about the project’s title in a conversation. Twenty-six images in various sizes were displayed in the show with migration certificates of the artist’s family from East Pakistan to India in 1959 and four days of newspaper cuttings regarding communal violence. Concept notes give some idea about the project’s concerns, and detailed information about the images or the materials provided in the shows needs to be precise. Some exciting layers open from a conversation with artists that portrays this multi-layered project narrating the polarised zones of violence between communities.

Trail of blood is a collection of images of people, space, and objects that tell us the story from different perspectives and tones regarding the communal violence and horrible past that they experienced in their life and still going in their veins of memory.

Real ”painful” stories

Artists started to tell the real stories behind these projects, and every image evolved into a storyteller of historical time.

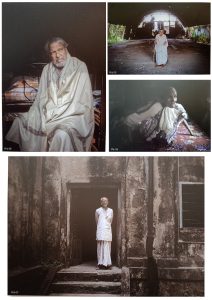

The government set up “Permanent Liability” camps for women and the elderly without relatives or male earners in their families. When the retaliation of the Calcutta Killing spread all over Bengal and India, Minu Roy (F 01) fled to West Bengal from Comilla (now in Bangladesh) with her two daughters, aged two years and six months. Her husband died in the riot. She spent the rest of her life in this camp. Even after 75 years of Partition, the Indian government failed to provide them with proper shelter. Her two unmarried daughters still lived in this abandoned Anatha (local name, meaning orphanage) camp.

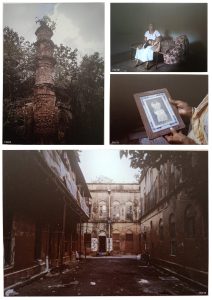

In 1946, the artist’s aunt, Gita Rani Banik (FN: 02), and mother, Kabita Saha’s family, fled from Dacca (now Dhaka) with one piece of cloth as the vengeance for the Calcutta killing spread through the nation. Unknowingly they took shelter at Debendra Colony, South Dumdum area, Kolkata, which was also a Muslim-dominated area. Some names of places indicate that fact, like Kazipara, Goruhata, and Masjid gate.

Several mosques were also attacked and demolished then (FN: 03). These places later served as shelters for the refugees from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). Many such migrants still live in this abandoned mosque of Beliaghata.

Hindu rioters used the roofs of these buildings (FN: 04) to store weapons and target the area’s Muslim residents. Localities such as Mia Bagan (near Koley Barack) bear the names of Muslim-dominated places but are no longer inhabited by Muslims. Muslim residents fled this area after the riot.

The immediate retaliation came after the great Calcutta killing on 10th October 1946, known as the Noakhali Genocide. Consequently, approximately 50,000 people became refugees, and most of those who survived migrated to West Bengal, Tripura, and Assam in India. Mrs Nirod Bala Debnath, aged 90, fled from Noakhali, East Bengal (currently in Bangladesh) and took shelter in the Ranaghat. Like other refugees, she took possession of the Nissen Hut, built during WWII to store food and ammunition, and moved in. The lady is standing in the same hut (FN: 05) where she took shelter with her family.

Niroda Debnath (FN: 06), 90 years old, is a victim of the Noakhali Genocide of 1946, which was the immediate aftermath of the great Calcutta killing. She fled Noakhali through a forest, lost her husband, and came to Tripurrah with her three children. As a single mother, she has raised her children by working as a maid in the nearby Ranaghat rail quarters. “The river water had become red, the fires were burning, and bodies were everywhere. My mind keeps going to all those screens throughout the night, and I can’t sleep”, says Debnath.

Amar Mallick (FN:07), age 85, was a victim who saw his two elder brothers being stabbed in front of his eyes by a Muslim mob in 1946 during the great Calcutta killing riot. His testimony revealed that he and his family had to flee their house for one year due to fear. After the India-Pakistan partition, they gained the courage to return home.

Rudraprasad Sengupta (FN: 08), a well-known theatre artist in India, is now 87. He stated, “was staying on Karbala Tank Road near Maniktala at the time of the Direct Action (16th August 1946). I vividly recall those days when one could kill another; their excitement roared as “Allahu Akbar”and “Bande Mataram” My elder brother was a teacher, so many students came to our house for tuition. On the day of direct action, one came, named Mujibbur Rahaman, and he got stuck in our home for some days; our mother instructed us to call him Mani da rather than Mujib da. When I was a kid, I never liked going to school. Another incident I recall is that I skipped classes most days and spent 3 to 4 hours sitting at the Dumdum rail station. One day, I saw a train passing by with dead bodies on each door. After so many years, I cried remembering those days”.

How did one image or the images become a historical subject to understand history? Photos tell more layered stories than any other historical objects; communal violence and social milieus harden in these frames. Partition is documented even though the horrors were not bearable, and museums were open for the audience. Calcutta’s great killing is not documented well for future reference; Saha is actively preparing for the continuous study of communal violence and the visual and textual documentation.

Krispin Joseph PX, a poet and journalist, completed an MFA in art history and visual studies at the University of Hyderabad.