Partha Dasgupta

Art infecting the city:

Festival comes at a definite time every year. This cyclical movement of event’s where creation and dissolution, coming together of a large number of people for a few days and then going back to their respective day- today lives, continues every year, leaving it’s indelible mark. Over time, things change. Sometimes, within a span of a decade or two certain social norms and way of life change drastically – dislocation of time as it may be called. This entire process, like the meandering course of a river continues ,leaving it’s imprints imperceptibly. By retracing these imprints the story of the social history of a place and it’s people can be unfurled and retold.

Festival comes at a definite time every year. This cyclical movement of event’s where creation and dissolution, coming together of a large number of people for a few days and then going back to their respective day- today lives, continues every year, leaving it’s indelible mark. Over time, things change. Sometimes, within a span of a decade or two certain social norms and way of life change drastically – dislocation of time as it may be called. This entire process, like the meandering course of a river continues ,leaving it’s imprints imperceptibly. By retracing these imprints the story of the social history of a place and it’s people can be unfurled and retold.

Durga puja of Kolkata exemplifies a vast array of different parameters of creativity over the ages. A practice of pandal (marquee) designing and idol making has flourished on this occasion which is a synthesis of contemporary art, as a number of practising artists and designers join hands to execute their ideas and concepts.

The huge living installations in Kolkata often include sculpture, light, sound, video and performance, as well as architectural, environmental or assemblage constructions – all of which invite unique artistic and spatial interactions. Some works also address notions of place, location and displacement. They also encourage viewers to rethink their own relationship to, and experiences with, art objects.

For the last eighteen years of my quarter-century old art practice, I have been experimenting with ideas of space division, introducing odd materials within the periphery of architecture, and exploring particular sites and travelling back with its social history.

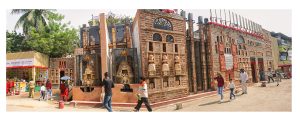

The final execution on the field is basically temporary in nature – this always establishes the feature of ‘displacement’. In 2013, I did a structure with ceramic insulators and spare terracotta roof tiles, covering an area of nearly 3000 sq mtr. This was the first experiment I undertook with unconventional materials for architecture. I built pillars, walls, cornices, cantilevers and also sections of roof with high-tension insulator props, kiln coil supporting grooves, giant fuse boxes and kitkats and spare roof tiles. All these materials I collected from the ceramics and tile industries with the intention of changing the identities of the objects. The final outcome made me more ambitious.

Here, let me quote Prof. Sunanda Kumar Sanyal (Lesley University College of Art and Design, Boston), who wrote in the catalogue of my solo exhibition, Amrit, in Kolkata, ‘What I find most important in Dasgupta’s attempt as a ceramist-painter to reach out to the expanded field of sculpture is a strong sense of totality in his work. While each of the exhibits has a distinct title and identity, “piece” or “work” is perhaps a misnomer for them; “ensemble” would be a more appropriate label.

‘This installation strategy with crucial attention to the totality of effect in the gallery is, without question, a translation of Dasgupta’s collaborative work in fabricating the public space of the pandals of Durga Pujo. Over the last couple of decades, institutionally trained artists have taken leading roles in embellishing the pandals of this most important annual festival in Bengali culture. Yet the question of the relevance of these projects to the local contemporary art has hardly received any critical attention. While many of the artists working in this arena claim to keep it separate from their studio projects, Dasgupta is one of those who do just the opposite: he consciously carries his technical and conceptual expertise to the designing of pandals, and in return, brings back the learning experience from there to the studio. For example, he has used a variety of utilitarian ceramic objects, such as bricks, roof tiles and manufactured electrical accessories to produce highly innovative designs in his Pujo projects. On the other hand, the lessons he learned from the arduous task of integrating the physical space of a pandal into the design for public consumption has become influential in his exploitation of the gallery space to produce a total effect. This environmental effect, I believe, is the culmination of all of Dasgupta’s creative inquiries into the discursive potential of ceramic, painting, and sculpture.’

‘This installation strategy with crucial attention to the totality of effect in the gallery is, without question, a translation of Dasgupta’s collaborative work in fabricating the public space of the pandals of Durga Pujo. Over the last couple of decades, institutionally trained artists have taken leading roles in embellishing the pandals of this most important annual festival in Bengali culture. Yet the question of the relevance of these projects to the local contemporary art has hardly received any critical attention. While many of the artists working in this arena claim to keep it separate from their studio projects, Dasgupta is one of those who do just the opposite: he consciously carries his technical and conceptual expertise to the designing of pandals, and in return, brings back the learning experience from there to the studio. For example, he has used a variety of utilitarian ceramic objects, such as bricks, roof tiles and manufactured electrical accessories to produce highly innovative designs in his Pujo projects. On the other hand, the lessons he learned from the arduous task of integrating the physical space of a pandal into the design for public consumption has become influential in his exploitation of the gallery space to produce a total effect. This environmental effect, I believe, is the culmination of all of Dasgupta’s creative inquiries into the discursive potential of ceramic, painting, and sculpture.’

From that point of time I started thinking of working with architectural clay objects that are considered permanent material in an area which is temporary in nature. It was not a very easy task to convince the Durga puja organizers who funded the entire project. They collected funds from corporate houses, got permission from the administrative authorities for mass gatherings of people during the puja days and they also had to ensure that certain regulations, particularly from the fire and electricity departments, were met.

I not only had to select the place and prepare a budget, but also had to choose organizers who could carry the entire project because it was not merely about decorating a place; rather, it was a kind of art and design movement.

Finally in 2018 all the rejections ended and I was offered the task of executing my plans at a site called ‘Thakurpukur State Bank Park’, in the southernmost end of Kolkata.

“Give me a brick and it becomes worth its weight in gold” – Frank Lloyd Wright

I chose to work with bricks.

Over a five-year period between 2013 and 2018, besides working in the public arts area, I travelled regularly to brick fields, worked with the artisans there to collect data and visited the parallel workshops at these sites where brick moulds were made and nameplates were carved by wood engravers.

I am very fond of Laurie Baker’s work and philosophy. I am not an architect but a practising designer with an inclination towards ceramics and architecture. Once when I was trying to design a space at a roadside festival where I extended my practices from the four walls of a studio to working in open air space, the ‘Bakerian philosophy’ of architecture acted as a motivational tool for me.

Working in this particular area is always a group effort. A group of likeminded people consisting of some ceramic artists, historians, students from Government Art College, Kolkata, clay workers, light designers, structural engineers, nearly thirty masons and twenty iron fabricators worked in this particular project for eight months.

For these types of projects, a few square metres of the city’s public spaces are offered. Sometime it is allotted directly on public roads, in parks or road junctions but often a disputed private property is also allotted. Thus, it is always surrounded by an urban hardscape with their own set of local history and a vast repertoire of memories.

Now let me come to the point that ‘why I chose bricks’.

The answers are plenty: 1) Bricks are the most common so-called permanent and traditional material for architects. 2) Because traditional materials like bricks have a portfolio of properties that are sometimes better than anything we have created recently. It is the whole ecosystem that matters. In the old days, the building materials we used were part of the landscape, and they were easier to recycle. New materials are not usually like that. When it comes to sustainability, traditional materials are often more efficient. And 3) The most important feature is shifting of a land mass in the form of brick.

This shifting is an important journey because the structures that we build during the puja are ephemeral in nature. We have to deconstruct the entire thing after five days. As bricks can be reused, they can be shifted from the site where it was used primarily.

I had conceived the entire pandal site, 100’ x 40’as a large multi chambered kiln installation which was actually fired on site with murals, pottery and clay images so as to familiarise the public with the entire process of working in terracotta.The area was sectioned into three zones consisting of seventeen kilns, straight and inclined walls, with a height of 32’, pocket kilns and the central Garbha Grih. Reused bricks were arranged to make the foundation and the team of art historians who worked with me started documenting the labels of bricks which were numerous. We found evidences of changing font styles, branding, references of place of manufacturing, bricks from government-owned kilns, even few that were labelled with ‘26th January’, maybe to mark the celebration of Republic Day. Basically, these are the marks of shifting – shifting of a landmass with marked history.

Nearly 60,000 bricks were made in the brick field located in South 24 Pargana beside the Ganges. Those bricks were 8’’ x 4’’ x 2’’ in size and was labelled with the name of the site, year, festival for which it was manufactured and with some geometrical shapes. Some of the bricks were fired on the site and rest were fired in the brick field.

Nearly 60,000 bricks were made in the brick field located in South 24 Pargana beside the Ganges. Those bricks were 8’’ x 4’’ x 2’’ in size and was labelled with the name of the site, year, festival for which it was manufactured and with some geometrical shapes. Some of the bricks were fired on the site and rest were fired in the brick field.

Kilns on the site were loaded with pots and were primarily covered with raw bricks, which finally were covered with fired bricks and were charged with wood for firing. These were kept as it is after firing, only removing the outer cover of pre-fired bricks, a part of the entire architectural innovation. Small pots were glazed and fired inside these smaller kiln chambers thus adding colours to the entire composition.

2018 was a remarkable year in the history of Indian ceramics because the first Indian Ceramics Triennial was held in Jaipur. I was fortunate to be a participant in the show. Here I met Jaques Kufferman, the clay artist who previously worked in a project with the brick field people in Maihar, MP. Jaques built an egg shaped kiln and fired it on site at the Jawahar Kala Kendra, Jaipur. I too, with few of my fellow artists, lent a hand in the installation and firing. Immediately after my return from Jaipur, I build a same-fashioned kiln with some alteration to Jaques’s design and it became a success. It was built at the front section of the site and was fashioned on Ravana, the mythological character with ten heads. The huge heads placed on top were made in raku technique.

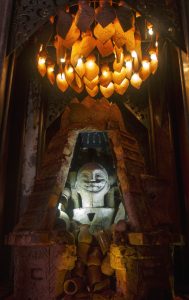

The idol was in clay and was placed inside a wall as a relief sculpture. I made that with pigments mixed with clay so as to give the sense of a self-coloured body. I called the entire installation as ‘Agnisuddhi’, purification by fire.

And then the final days came when I had to dismantle the entire installation. I knew that and thus I put name tags on the bricks. Bricks from the deconstructed site are now resold to customers from different places of West Bengal and history starts flowing through this process. Pieces of land are still travelling today in the form of bricks, not only which I made but all bricks made for shaping architecture also shape history.

Touch is the most direct and least analysed of our senses; it is the grounding sense, the sense of tangibility as the proverb states, ‘Seeing is believing, but feeling is the truth.’ It is beyond doubt that in our society, hegemony of vision overshadows our tactile awareness. However, this hegemony is now being challenged across many fields, including philosophy, psychology, anthropology, cultural studies as well as in the world of art. A long history of touch engagement has given people an intimate understanding of the tactile qualities of fired clay and has made placed ceramics in a good spot to challenge visual dominance. Creating sculptural forms in clay that are intended to be touched and handled helps boost this challenge.

This journey of transformation which has a beginning, middle and an end is never questioned, argued or challenged by the one who is touched. Just as holding hands slows us down and makes us aware of each other, the power of this touch is profound, especially in our current, socially mediated culture. The maker intimately handles the ‘touch hunger’ quality of the malleable material. Each tactile quality of clay is a historical document of the innocence, intellect and sensibility of the creator.

Working with clay proves to be another addition to the preservation of history in the field of ceramics in India, when the world is witnessing the changes in clay over time and realizing that ceramics is everywhere in people’s lives.

Links for viewing-

- https://www.youtube.com/hashtag/kolkata_durgapuja

- https://www.youtube.com/hashtag/durgapuja_artisan

- http://www.durgaonline.com/2018/sbparkthakur

- SB Park Sarbojanin Durgotsab

The article is published on ‘MRIN- A Journal of Indian ceramic Art’

The digital copy is provided by Shampa Shah