Welcome to Samvaad, where art meets conversation, and inspiration knows no bounds. Here we engage in insightful conversations with eminent personalities from the art fraternity. Through Samvaad, Abir Pothi aims to create a platform for thought-provoking discussions, providing readers with an exclusive glimpse into the creative processes, inspirations, and experiences of these creative individuals. From curating groundbreaking exhibitions to pushing the boundaries of artistic expression, our interviews shed light on the diverse perspectives and contributions of these art luminaries. Samvaad is your ticket to connect with the visionaries who breathe life into the art world, offering unique insights and behind-the-scenes glimpses into their fascinating journeys.

In this edition of Samvaad, we look into the world of architecture with Jignesh Modi, an esteemed architect hailing from Surat. Engaging in a conversation with Nidheesh Tyagi from Abir Pothi, Jignesh shares insights into his career journey, the architectural landscape of Surat, and his unique approach to design.

From discussing Surat’s rich history as a forward-looking city to envisioning its future as one of the fastest-growing urban centres globally, Jignesh paints a vivid picture of his hometown’s evolution and aspirations. He emphasizes the importance of preserving Surat’s cultural identity while embracing modern advancements and global influences, striking a delicate balance between tradition and innovation. Jignesh further elaborates on his experiences in the field, highlighting the collaborative efforts involved in creating transformative architectural projects. Drawing from his partnership with his wife Monica, also an architect, he reflects on the division of labour, the significance of originality in design, and the value of encouraging creativity within the team.

Touching upon the evolving role of technology in architecture, Jignesh challenges the notion that complexity equates to superior design. He advocates for a human-centric approach, emphasising the need for spaces that prioritize functionality, comfort, and user experience over mere aesthetics. Throughout the discussion, Jignesh shares anecdotes, challenges, and triumphs, offering valuable lessons for aspiring architects and designers. His dedication to authenticity, innovation, and community engagement serves as an inspiration, underscoring the transformative power of architecture in shaping societies and enriching lives.

Join us as we embark on this enlightening dialogue with Jignesh Modi, exploring the intersections of tradition and modernity, creativity and pragmatism, and the timeless allure of architecture in shaping the world around us.

For Part-1 (Click Here)

Nidheesh: I think it’s also about how we have moved from those picture postcards kind of things being replicated to experiential things that we want to experience living. It’s like living that thing, as otherwise earlier, I think when I was growing, I come from Raipur, and I could see that lots of houses were like there, lots of facades outside, but then functionally, those houses are not so. But today, I think how houses have changed. You were talking about the end user. I would want you to kind of run through this, your textile market project you have done. How did you think about it, the scale of it, and the people who are going to use it, and how did it come up, like what all the factors, what all factored into it into that?

Jignesh: So, we always make sure that whatever we design, whether it’s the smallest, like just doing a traffic island, a very interesting traffic island which is coming up (I wish I could share photographs; it’s still in the process), to the largest, to the smallest residences to the largest commercial spaces that we do, we always think of the end user. Because when you’re doing a private residence, the end user is a family, a small family or maybe a mixed family, a joint family, but they have their own privacy, they have their own space, because they can spend that kind of money for such facilities.

But when you are doing textile markets, when you’re doing such huge textile markets like 4 million square feet, 40 lakh square feet of space, now how do you make people over there relate to that space? Number one, because these workers who are there, say, the textile market of 4 million square feet would have almost 1,000 owners, but it would have almost 200,000 people who are working in that place. Now, how do you design that space for 200,000 people who are low-income, who are labourers, and they feel at home in that place? They feel that freedom of space, they feel like working there, they feel that they can express themselves over there. How do you do that?

So, I would just give an example of this huge market that we’re doing. We came up with a concept of “chowks.” Now, “chowks” are plazas which are prevalent all over the world. They are not open courtyards because I think that’s something which we do with private villas. But these chowks, because it has to be enclosed, but a space where, when you are standing there, you can meet up with people, you can talk to other coworkers, you can get there, you can enjoy your breaks over there. So, we devised this idea of chowks. That was number one, which was a very successful kind of an idea. People kind of spend their time over there, their free time, talking and chatting with each other, enjoying that airiness, that light, that space over there. Even some people used to come and bring their work over there and sit and do their work.

Then we, the another idea was having wide passages. What we have seen till now was that, okay, 2-meter passages were sufficient in markets, but we devised almost 4.5 meters of passages, which brought in a lot of light, which made living there possible, lively, and the kind of movement that happened there did not make it claustrophobic.

Another idea which we came up with was that, though the shops and the showrooms that were included in that space were double-heighted, but there was a mezzanine, so it gave you less height, but in all the common open spaces, the height was almost 6 meters, that is 20 feet, so that a freedom of movement, because these people, the end users, which I would say are not the owners, but these 200,000 labourers, they don’t have a space to go, they don’t have a space to enjoy. So, for them, this was kind of something which they never imagined that this would happen to them at their workplace, and that is most important. If the end user is finally happy to go to work, then I think you have achieved something in your design.

Nidheesh: Yeah, it must be quite a logistical challenge to get those people coming in and going out.

Jignesh: Yeah, it’s a logistic nightmare. We have around 42 escalators, and around 120 elevators, all full-sized. We have parking for tempos and trucks of almost 2,000 tempos and trucks can park at a time. A lot of those things are automated so that it’s a nine-story, double-heightened market, each story is double-height. So, a nine-story market, which is around 600 feet by 2,000 feet. So, how does the packing which happens every evening in all those 5,000 offices, their big parcels, because the time is limited between 7 to 9, the packing happens, everything is sent to trucks in the basements, in the lower basement, on the ground floor. So, the use of escalators in a way, we have travelators where these parcels travel from your go-down to the truck which is parked over there, and it reaches the exact same place where it is supposed to reach. So, there is no intermediary from the office, from the go-down to the truck parked only there. It is kind of loaded and unloaded, that’s it, otherwise, it reaches where it is supposed to reach.

And then there are things to do about because in such a huge space, you have to take care of the firefighting, right? You have to take care of proper lighting. So, all these things, where we have a lot of consultants involved. Obviously, we can’t do it all on our own, and a big support from the builders also, they are very well-known builders in Surat.

Nidheesh: I also wanted to pick your brain about having some kind of increasing aesthetic quotient in public spaces. One of the things which we notice in non-metro places is that cities are mushrooming very fast, and there’s some kind of shortchanging happening in these public spaces. Getting that aesthetic in place also brings loads of artists and sculptures into the picture. Most of the cities have fewer playgrounds, correct, more ornate parks, but again, smaller spaces, now fewer places to walk, these public spaces. Since you were talking about the end user and the city is also like a machine or a kind of a thing to use, how do you see that happening in these cities in India?

Jignesh: We are in a difficult place right now. We need infrastructure, we need wider roads, overpasses, metros. So, how do we balance all that? And then, we are losing the public places, public spaces. And when we are putting in all these infrastructure giants, we lose a sense of identity. When you’re traveling on the road but you are below an overpass, so you don’t know where you’re going, you can only see the pillars, there’s Metro going on. Now there are multiple layered bridges. Surat is known for its flyovers, we have 167 or so all right in a span of a decade or decade and a half. So, when I’m traveling now and I sometimes feel lost, sometimes I also wonder where things are going, whether at what cost. You are in a maze and you lose the sense of direction.

Okay, that’s all fine, but then what happens is it’s creating a lot of negative spaces. Under the flyovers, you have wider roads, but then you have the pillars of the Metro, you know, coming in. You have the Metro stations, huge structures which I don’t know whether there’s any planning, aesthetic planning involved or not. But what we can sense is there is no aesthetic planning, they are just placed where it is convenient, and it creates a lot of dark and negative spaces.

I don’t know if the government or the municipal corporations are getting a little bit active now. In the last few years, what we’ve seen is they have tried to rejuvenate the spaces below the flyovers, where they make it more people-centric, where people can come together because it’s a shaded place. So, either you leave it as it is where encroachers would come and occupy those spaces and it becomes darker and more lethal for society, or you do something about it. So, I believe that they are now trying to take the help of architects, planners, designers, landscape architects, and artists, and trying to create spaces. That is one positive aspect after a long, long time that I’m seeing.

The second thing is that all these traffic islands used to be just something which went around and you never knew why you were doing this. Even if it was not there, it wouldn’t make sense. But now, people are coming forward, companies are coming forward. It’s a partnership with the local bodies. We are doing one traffic island just near the station where it was a competition and we won the competition. Earlier, it used to be just given like that to whosoever wanted to sponsor it. Now, it’s a competition because a lot of companies are coming forward to claim that space, to design it, and to make it more people-friendly, for taking selfies, for people to enjoy these spaces.

My wife, Monica, who’s also an architect, she kind of handles all the interior projects and all these aesthetic, I would say, the aesthetic part of our designs. And we’ve come up with this. Surat City is a city of textiles and fabrics, right? If you’ve seen that epic Marilyn Monroe picture which has her floating, you know, yeah. So, it’s not exactly that, but our idea in that particular traffic island is to kind of tell a story about Surat. It’s a city of textiles, textiles float just like the dreams of the people of Surat. It’s in the air. We have kept it very small, sleek supports where this whole structure is floating. We made it look like a fabric, we used perforated steel jalis and gave it a canvas kind of look. So, it is the canvas of the life of the people of Surat, the city of textiles. It is floating just like the dreams of the people of Surat. And then, it is soaring above the road, the circle, the surface, and which kind of very aptly catches the aspirations of everyone in this city. And then, it is kind of lighted very colourfully so that aspect of maujilo Surat comes in, the rangilo Surat comes in, yeah, which kind of reflects that life is all about, it has to have colours, it has to have dreams, it has to have aspirations. So, I think we try and involve ourselves wherever required, and it gives a great sense of freedom when you do these things.

To be Continued…

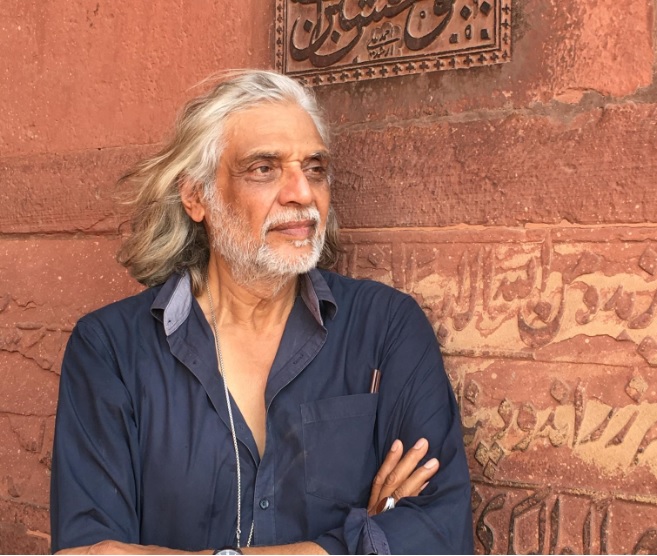

Feature image: Nidheesh Tyagi (Left) in conversation with Jignesh Modi (Right)