Chris Ofili is a British Black artist known for using elephant dung in Artwork. Ofili (born 10 October 1968) became noticed in a 1996 group exhibition of young British artists at the Brooklyn Museum in New York because of some works, including Ofili’s work, highly provocating to the aristocracy. Ofli’s Black Virgin grabbed the most attention in this exhibition, using elephant dung to support the canvas to stand. This elephant dung element with the Virgin Mary artwork provoked the Catholic mayor, conservative media and the Church, who turned against Ofili’s work.

Christopher Ofili, popularly known as Chris Ofili, was a Turner Prize winner and one of the Young British Artists. He was only 30 when he won this prestigious award. Since 2005, Ofili has lived and worked in Trinidad and Tobago, where he presently lives in Port of Spain. He also has lived and worked in London and Brooklyn. Ofili studied at Tameside College and then at the Chelsea School of Art and the Royal College of Art in London and was very successful at a young age.

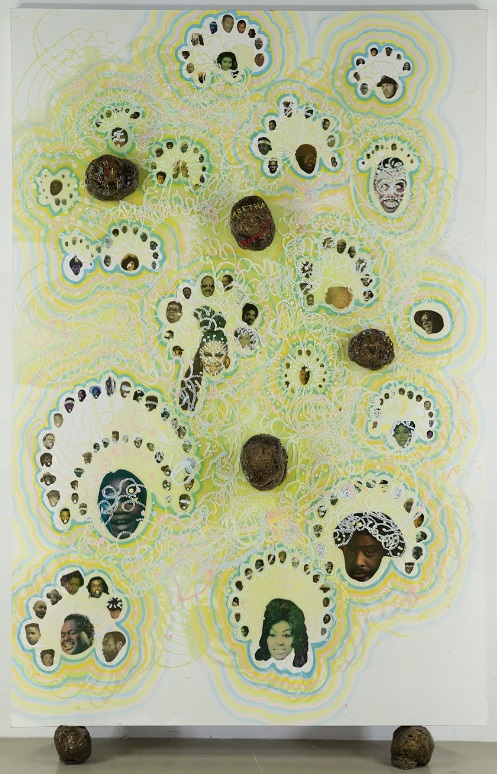

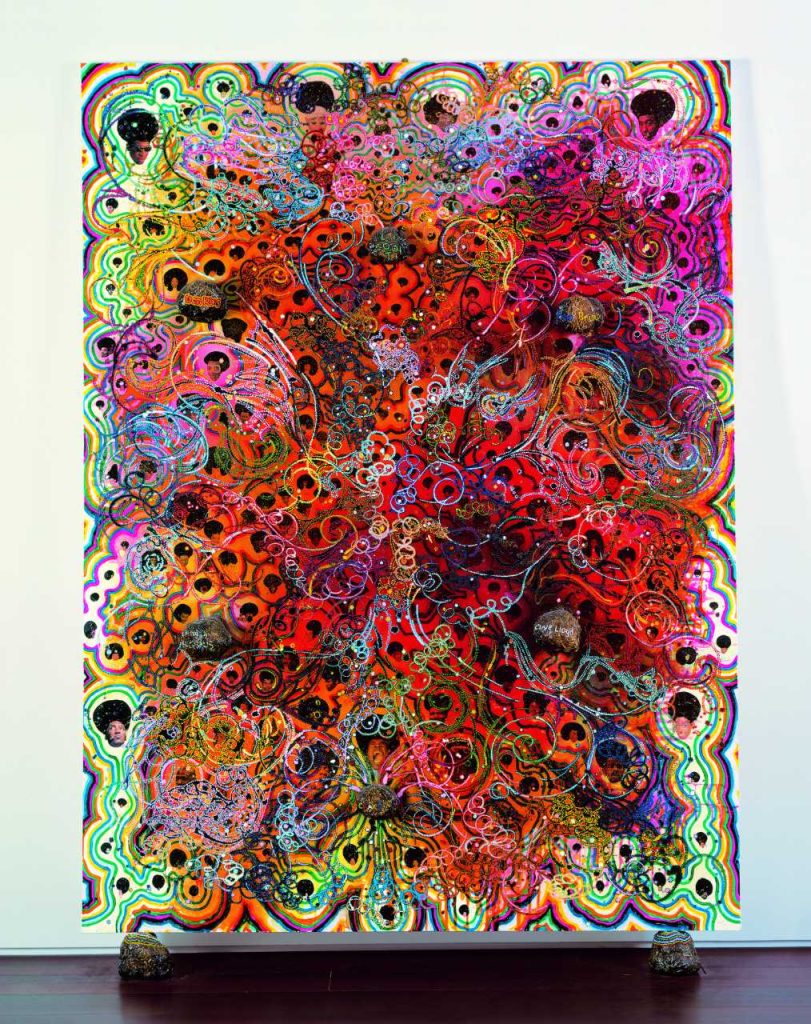

Ofili starts to problematise the presence and absence of blackness in contemporary society and the setting of the aristocracy. Ofili portrays the complex environments embroiled with problems of our community which are not seeable directly, nuanced with a set of religious and socio-political issues. Ofili’s use of elephant dung made him controversial and scandalise, and he became famous for using unconventional craft materials such as glitter, map pins, glue and collage. Ofili always creates seductively brightly coloured paintings that echoed with African life and dreams, detailed with stories and images, heavily layered with the meticulous narration of African soil that gives a fresh ambience at each time. The artist records and glorifies Black affairs, memorialising and harrowing racist brutality, and frequently returns to themes of religion, mainly as shown throughout art history.

A scholarship allowed Ofili to visit Zimbabwe in Africa when he was 23; he was amazed by cave paintings he saw in the ancient caves, which were made from hundreds of dots that helped him create a new visual language. The major shift Ofili got from Africa was the presence of elephant dung; he saw many on the ground and even managed to bring some elephant dung back with him. After visiting Zimbabwe’s caves, Ofili produces Artwork with the influence of dotty cave paintings and inquisitive elephant dung. He started to use a small ball of elephant dung to stand for the Artwork on the display. Some of the audience never accept this material’s use, and they are angry at him for making this Artwork with elephant dung.

Why is elephant dung, not an Art material? Why are people with a conservative mindset upset and turn against Ofili’s Artwork?

In Seven Deadly Sins, the devil is foremost in all seven of Ofili’s large-scale and profoundly intricate paintings. Seven Deadly Sins are a complex narration of religious ideas, beliefs, fertility gods, the temptation of the devil, and numerous hidden things. Through this work, Ofili seizes your eyes and soul, making you aware of what is seeing and what seeing is. The artist is conscious when he does the Artwork and invites the audience’s conscience to engage with his work. The Seven Deadly Sins narrate a visual story of Sins and Devils, through the ignited surface to a depth of horrors, between figures and foliage, light and dark, and significant elements like religion, the sacred and profane world of belief system.

Ofili’s inspiration from the music is apparent in his paintings, as they merged with as many ideas and urban myths. The rhythmic prologue of hip-hop rerouted Ofili’s art practice into strange lands and visual rhythm. He tries to bring back the African aesthetics they lost through his Artwork. Life between light and dark or the visibility and opacity of the African culture and black people, retelling the geometrical air in a loosely conveyed style.

‘Ofili is positioned as a painter interested in the history of his chosen medium who believes in painting as a spiritual act, writes Alice Correia. The artist stands in a position and starts doing a visual memory of a privileged community’s existing idea of life and social setting. How can we understand that Ofili’s painting’s visible and invisible elements are making a mark on art history, as they are imprinted in human history?

Krispin Joseph PX, a poet and journalist, completed an MFA in art history and visual studies at the University of Hyderabad.