Introduction

Despite socioeconomic challenges, Iran remains an innovative country in terms of arts and culture. Art has been utilised by contemporary artists to challenge biases, disrupt norms, and critically evaluate society and mankind. Iranian artists have formed a universal vocabulary and led the global art scene in the last four decades, refusing to be constrained by traditional constraints. This article will focus on emerging and established Iranian artists who are exploring lens-based practices both within and outside of Iran. It will also look at the origins and development of the Modern Art Movement in Iran, which has been a landmark event in Modern Iranian art, as well as the latest advancements in lens-based practises.

The Rise and Development of the Modern Art Movement in Iran

The contemporary art movement in Iran emerged in the late 1940s and early 1950s after Reza Shah’s exile and increased interaction with the West. ‘The College of Fine Arts in Tehran’, under André Godard’s supervision, aimed to develop a modern Iranian language. Artists like Marcos Grigorian, Parviz Tanavoli, and Siah Armajani drew inspiration from Iranian history and popular culture. Iran was introduced to the global art scene in the 1960s and 1970s, with artists engaging in exhibitions, establishing galleries, and attracting foreign collectors. ‘The Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art’ showcased an extensive collection of both Western and Iranian artists, in 1977.

The 1979 Revolution altered Iran’s art scene, with the Iraq War dominating the art of the period. Sadegh Tirafkan created a series of photographs in tribute to his friends who died in the war, and the conflict also aided in the development of graphic arts. Some Iranian artists, including Shirin Neshat, grappled with concerns of exile and identity and addressed “forbidden” subjects such as Islam, revolution, women, femininity, and violence.

Notable Photographers in Iran

Sadegh Tirafkan (1965), an Iranian artist and photographer, was a complex individual who resisted labels and focused on the individual character constantly vying between past and present, ancient, and modern belief systems. He was born to devout Muslim Iranian parents in Iraq, Tirafkan’s childhood and adolescence were shaped by war and revolution as the family fled to Iran soon after his birth. After the overthrow of the Shah in 1979, he volunteered to serve in the Basiji, a poorly equipped people’s militia. His interests at the time were cultural and aesthetic, but he also learned to shoot a rifle.

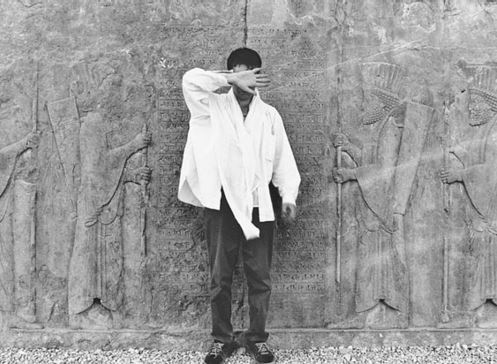

After graduating in 1989 from Tehran Fine Art University, Tirafkan was given a government voucher that allowed him to subscribe to a magazine called “Creative Camera,” which gave him precious glimpses of Western photography. An invitation to exhibit in Paris opened a career opportunity for him outside of Iran, including a brief period of living in New York in 1997. Interestingly, Tirakfan’s time in the West had the effect of putting him more deeply in touch with his Iranian cultural and aesthetic roots. Now a practising postmodernist, Tirafkan returned home to create “Persepolis,” Iran’s first conceptual video installation, in which the artist poses amidst the ruins of ancient Iran’s imperial city.

A video still from “Persepolis” © The Estate of Sadegh Tirafkan, http://www.johnseed.com/

A video still from “Persepolis” © The Estate of Sadegh Tirafkan, http://www.johnseed.com/

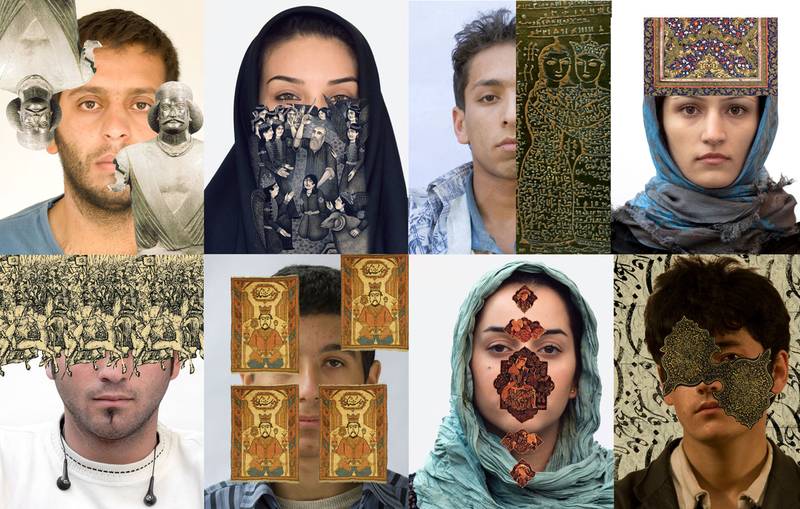

Sadegh Tirafkan, a conceptual artist with roots in photography, explored themes of masculinity and identity through his mature photographs, digital collages, installations, and videos. His photo series “Iranian Man” was inspired by ancient drawings from Takht Jamshid and Persepolis, where a man hides his face behind a red cloth/towel, possibly ashamed of his past. The series also featured Tirafkan’s bare torso decorated with block stamping, calligraphy, and tattoos. Tirafkan’s self-portraits evolved into digital collages that made broader cultural commentaries. In the last decade of his life, he orchestrated layered vignettes of heroism, athletic prowess, and self-flagellation, while his “Endless” series frames images of daggers and combat in a dance of death and intimacy attempting to represent a different side of his culture which addressed cultural and religious aspects of his origin.

Sadegh Tirafkan, The Loss of Our Identity, 2008, https://www.mutualart.com/

Sadegh Tirafkan, The Loss of Our Identity, 2008, https://www.mutualart.com/

In 2006, Tirafkan turned his interest to the problem of Iran’s growing population. He created his “Multitudes” using a digital collage and the metaphor of a human carpet. The carpet is emblematic of Persian culture, symbolizing culture, seasonality, richness, diversity, and continuity in time and history. The work spoke about the silencing of females, which is not just a Middle Eastern concern but universal. In his final decade, Tirafkan made regular visits to the U.S. and Canada but remained deeply Iranian in his heart, deeply proud of his culture. Acclaimed both in Iran and the West, the artist died a revolutionary of another kind. To summarise, Sadegh Tirafkan’s work explores themes of masculinity, identity, and the struggle for inner peace and sanctity in Iranian society.

Shadi Ghadirian (1974) is an acclaimed photographer of Iran noted for her work highlighting challenges that women face all around the world, such as censorship, restrictions, barriers to self-actualization, and the clash between traditions and modernity. “Unfocused” (1998), “Qajar” (1998), “My Press Photo” (1999), “Like Every Day” (2000), “Be Colourful” (2002), “West by East” (2004), “Ctrl+Alt+Del” (2006), “Nil, Nil” (2008), “White Square” (2009), and “Miss Butterfly” (2011) are among her nine series of photographs, that were celebrated worldwide.

Ghadirian began her creative career in 1997, with her first solo display in 1998. The series featured black and white images of women dressed in traditional Qajar clothing, but the scenes also included elements unrelated to the historical setting, such as a Pepsi can, television, canvases, a hoover, or a contemporary newspaper with the work’s production date. These photographs demonstrated cultural shifts as well as an attempt to raise awareness and advancement. Despite criticism for simplifying the subject to a single picture with a simple, straightforward interpretation, Ghadirian’s “Qajar” series has a visual and conceptual appeal for the 1990s Eastern audience as well as Western audiences unfamiliar with Iranian culture.

Shadi Ghadirian, ‘Untitled’ from Qajar, 1998, digital print, 100 × 70 cm, https://darz.art/

Shadi Ghadirian, ‘Untitled’ from Qajar, 1998, digital print, 100 × 70 cm, https://darz.art/

Shadi Ghadirian, ‘Untitled’ from ‘Like Every Day, 2001, c print, 183 × 183 cm, https://darz.art/

Shadi Ghadirian, ‘Untitled’ from ‘Like Every Day, 2001, c print, 183 × 183 cm, https://darz.art/

Her work, “Like Every Day,” drew harsh criticism after it was shown at the Silk Road Art Gallery. The series comprised 17 photos depicting a woman’s torso on a white backdrop in the centre of the image, with unidentified ladies holding culinary implements before their faces and dressed in prayer chador in various colours and patterns.

Shadi Ghadirian, ‘Miss Butterfly #6’, 2011, archival digital pigment print, 70 × 100 cm, https://darz.art/

Shadi Ghadirian, ‘Miss Butterfly #6’, 2011, archival digital pigment print, 70 × 100 cm, https://darz.art/

Ghadirian’s most recent series, “Miss Butterfly,” was exhibited at the Silk Road Art Gallery in 2011. The series consists of 15 black and white photographs depicting a woman sitting on the stairs in the dark, standing in front of a window or under an opening in the ceiling, spinning a web across the entrance of light in a space that is sometimes minimal and sometimes fully real, and is inspired by Bijan Mofid’s play of the same title. Ghadirian’s artwork has been acclaimed across the world and has been on display in prominent art galleries and museums from 2000 to 2012.

Newsha Tavakolian (1981) and Meherdad Afsari (1977) are two young emerging photographers based in Tehran, Iran. Newsha is a distinctive artist of her generation. As a self-taught photographer, she began her career as a photojournalist at the age of 16 photographing guerrilla combatants in Iraqi Kurdistan and Syria. She began by writing for the Iranian press and eventually collaborated with the New York Times. Tavakolian has covered a wide range of current affairs during her career, including Iran’s 1999 student riots, the Iraq war, and presidential elections.

Newsha Tavakolian, ‘Untitled’ from ‘Listen,’2010-2011, https://www.artsy.net/

Tavakolian’s work eventually evolved into a hybrid of art and documentary photography. Her socially open-minded, humanistic pictures frequently reflect cultures in transition. Many of her more intimate images have been the focus of international exhibits. For example, in a 2014 show named “Burnt Generation,” she displayed photographs of the private lives of Tehran’s middle-class youngsters, inspired by the experiences of her close friends and neighbours.

‘Look,’ Newsha Tavakolian, part of ‘Burnt Generation’ at Somerset House, London, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/

‘Look,’ Newsha Tavakolian, part of ‘Burnt Generation’ at Somerset House, London, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/

The photographs were created to counter Western media prejudices by providing a more genuine depiction of life in Iran. Her work has been widely shown across countries, including institutions like the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the British Museum, and the Museum of Fine Arts, in Boston. Tavakolian has received several awards for her photography and was named a Magnum associate photographer in 2017.

Mehrdad Afsari is a photographer, documentarian, and video artist and an Iranian Visual Arts Society’s honorary member. His captivating paintings often do not include human characters; instead, they represent the mystical and immaculate features of nature and landscapes, while highlighting life’s fragility and limits. Travelling around Iran in pursuit of views, Afsari captures lyrical characteristics in his selected locations that others may overlook. He welcomes spectators into his excursions to discover illumination, harmony, and beauty through analogue photography. He portrays the ephemeral aspect of life and the human-nature link.

Mehrdad Afsari, from the series “Desolation Memories,” 2014, https://www.artsy.net/

Mehrdad Afsari, from the series “Desolation Memories,” 2014, https://www.artsy.net/

A vivid example of Mehrdad Afsari’s work on display at Mohsen Gallery, https://www.harpersbazaararabia.com/

A vivid example of Mehrdad Afsari’s work on display at Mohsen Gallery, https://www.harpersbazaararabia.com/

Emergence of the Staged Photography Genre

Following the 2009 post-election protests, ‘staged photography’, a genre distinguished by technical, ornamental, and dramatic advancements, became a popular alternative for an increasing number of photojournalists and aspiring photographers in Iran. Protests erupted in response to the disputed re-election of then-President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in June 2009, with dozens murdered and thousands imprisoned. Authorities launched an intense investigation on everyone holding a camera to prevent photographs of the disturbance from reaching around the world.

“Today, the dominant modern Iranian photography is staged. It’s very difficult to do documentary photography in Iran. It is restricted in most places, such as the streets and public places.,” explains Rozita Sharafjahan, proprietor of the Tehran-based Azad Art Gallery.

According to media reports, 170 journalists, photographers, and bloggers were imprisoned as a result of the protests, resulting in job losses and a substantial number fleeing Iran. ‘Staged photography’, which emphasised social, cultural, or historical concerns, evolved as an alternative. This genre, popularised in the 1980s by Western artists such as Cindy Sherman and Jeff Wall, allowed Iranian photographers to circumvent government constraints and create scenic or dramatic effects. Staged photography may be divided into several themes and styles of representation, namely, uncovering life’s fragility, A storytelling tradition, recording tragedies, Chador Art and alluding to wider social issues.

In staged photography, characters and objects are arranged for picturesque or dramatic effect, photograph by Armin Amirian, from the 2015 Analogy series, https://www.middleeasteye.net/

In staged photography, characters and objects are arranged for picturesque or dramatic effect, photograph by Armin Amirian, from the 2015 Analogy series, https://www.middleeasteye.net/

Armin Amirian, a young Iranian photographer, has embraced staged photography because it gives him the opportunity to produce unique imagery. He appreciates digital photography and manipulating photographs using applications, focusing on creativity rather than surface editing. Amirian’s photography is reminiscent of a centuries-old Iranian storytelling tradition, such as Naqqali (storytelling) and pardeh khani (curtain reading), in which narrators relate stories celebrating national or religious heroes. His photography is like these curtains in that it tells stories rather than depicting wrecked scenery or important occurrences. In his series of works, Amirian has adopted this narrative style of representation. He asserts that ‘whenever Iran had the opportunity to grow and prosper, numerous reasons stopped its growth, just like a weaned infant.’ Amirian’s photography highlights the country’s effort to adapt and progress, emphasising the significance of storytelling in Iranian culture.

Akhlagi says her work was inspired by the death of Neda Agha Soltan in the 2009 protests, which was captured on video, Photograph by Azadeh Akhlaghi, https://www.middleeasteye.net/

Akhlagi says her work was inspired by the death of Neda Agha Soltan in the 2009 protests, which was captured on video, Photograph by Azadeh Akhlaghi, https://www.middleeasteye.net/

Azadeh Akhlaghi, a talented photographer, focused her ‘By an Eye Witness’ collection (2009-2012) on political subjects. Using a large crew of professional actors, photographers, and costume designers, she rebuilt the deaths of dissidents and opponents of the former Pahlavi monarchy. Because the narrative is fictitious, Akhlaghi’s art is not necessarily characterised as staged photography. Instead, she incorporates historical events into her writing, such as assassinations, murders, and deaths. She intends to document these catastrophes because there are few photographs of modern Iranian history, and it was even banned from discussing them. Many of the persons in her work do not even have graves, so she had to imagine them.

Conclusion

Iranian photography has evolved significantly over the years, exploring a variety of subjects through bold, innovative, and metaphoric styles. It delves into cultural prejudices, social dilemmas, uncertainty, and religious beliefs. Iranian photographers have pushed boundaries in capturing Iranian people’s lives, introducing ‘staged photography’ concepts that highlight life fragility, storytelling tradition, disasters, and social and economic challenges. This language has become a prominent part of Iranian lens-based practice worldwide. The practice has expanded to include hybrid methods like documentary, photomontages, installation, analogue photography, and video/photo installations changing the face of contemporary Iranian art in the field of lens-based practices.

References

Online Articles:

- Tarannom Taghavi, Omid Armat (Trans.), 14th September 2022, “An Analysis of Shadi Ghadirian’s Works”, Darz Magazine

- Leila Sajjadi, 18th September 2019, “10 Iranian Artists who are shaping contemporary art”, Artsy Net

- Scheherezade Faramarzi, 27th November 2019, “Beyond Realism: Iran’s Photographers Recreate Images of Nation”, Middle East Eye,

- “In memoriam: Sadegh Tirafkan (1965 – 2013), 26th May 2013

- Maryam Ekhtiar and Marika Sardar, October 2004, “Modern and Contemporary Art in Iran”, In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000

Contributor