Fort Kochi is one of the earliest European settlements in India, dominated and inhabited by European settlers since the 16th century. In the shape of bungalows, street houses, significant structures, and bazaars, the Portuguese, Dutch, and British left a lasting effect of their cultural signature on the region. As prominent historical landmarks with importance to medieval architecture, they stand out. Fort Kochi is crossed by several streets, each with distinctive historical features. Preserving this cultural diversity and legacy may boost domestic and foreign visitor arrivals, increasing the local economy.

The Portuguese, Dutch, and British were among the colonial powers that formerly ruled the area, and their marks may be seen in Fort Kochi. With buildings like the Santa Cruz Basilica, St. Francis Church—India’s oldest church constructed by Europeans—and Fort Immanuel, a Portuguese fort built in the sixteenth century, the region’s architecture reflects this varied colonial past. The distinctive combination of European, Indian, and Arab architectural forms found in Fort Kochi’s architecture reflects the blending of cultures brought about by trade and colonization. An iconic representation of this blend is the Chinese fishing nets along the shore, which are thought to have been brought in centuries ago by Chinese traders.

Fort Kochi is only a neighbourhood or area southwest of Kochi/Cochin, not a traditional colonial fort; the name comes from Fort Manuel, part of a strategic partnership between the Portuguese navy and the King of Kochi and is regarded as the first Portuguese fort in Asia. Kochi was taken by Hyder Ali, the Sultan of Mysore, before the British Raj; after the Portuguese, the Dutch briefly ruled the city through Zamorin of Kozhikode. This narrative of Kochi’s history makes it appear like a straight line: a violent time leading up to the British Raj, with little impact from the colonial wars on a cosmopolitan laity that had been developing for generations.

Kochi’s beginnings can be traced to the quasi-mythical port of Muziris, which is thought to have existed in the adjacent district of Kodungalloor. The most common way to historicize Muziris’s existence is to mention it in Pliny the Elder’s second-century writings, albeit the particular text needs to be cited or identified. A great flood that destroyed Muziris in the middle of the fourteenth century is also said to have given rise to the port of Kochi, which served as a perfect substitute for the port that was so important to the ancient spice route (some accounts even suggest that Kochi’s establishment was made possible by Muziris’ destruction). The location, which the traders frequented, quickly drew people looking for spices. Fort Kochi became a trading centre for spices, mainly the highly prized black pepper in the Middle East and Europe.

The gastronomic landscape of Fort Kochi reflects the city’s ethnic past; dishes from the area reflect influences from Portuguese, Dutch, and Arab cuisines. On the other hand, Kerala’s restaurants and street food vendors also thrive with the state’s unique cuisine, distinguished by its coconut, spices, and seafood use. Hindus, Christians, and Muslims are among the religious groups who call Fort Kochi home, and they all contribute to the region’s rich cultural diversity. Religious holidays like Christmas, Eid, and Onam are widely attended, demonstrating the unity and diversity of world religions.

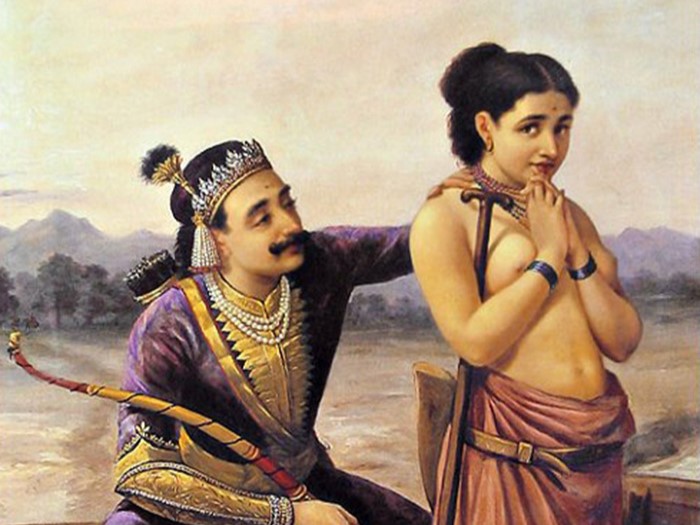

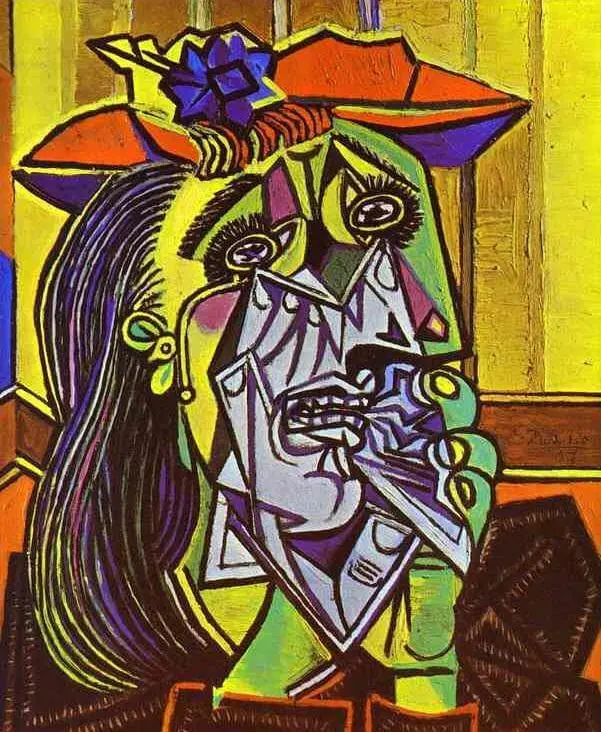

Fort Kochi has traditionally been a gathering place for thinkers, authors, and artists. Every two years, the Kochi-Muziris Biennale is an international exhibition of contemporary art that draws artists worldwide. Kerala’s rich performing arts history, which includes Kathakali, Theyyam, and Mohiniyattam, is honoured in Fort Kochi with several festivals and cultural events. The Kerala Kathakali Center is where visitors may witness these colourful artistic expressions.

The last Jews of Kerala

Edna Fernandes, writer and journalist, writes about Jewish culture and history in her book, ‘The Last Jews in Kerala, and about Fort Kochi briefly: ‘In 1341, it was nature, not man, that decided the fate of the Cranganore Jews and changed the course of the community. As a result of a torrential downpour of rain, the River Periyar flooded, silting up the harbour mouth. Because of this biblical-style flood, Cranganore lost its strategic maritime position. A new harbour was formed at Cochin that was smaller than the last but would replace Cranganore as the regional port. It was called Kochazhi, or “small estuary, ” or ” Kochi or Cochin. Faced with this natural disaster, the first party of Jews left for Cochin. The Jews settled in swiftly. Indeed, by 1345, a synagogue was built there. It was the Kochangadi synagogue and the first outside of Cranganore’.

According to Edna, the Jewish layer is the most significant element added to Kerala broadly and flourished for centuries with stories and cultural heritage. ‘Cochin was to become forever associated with the Jewry of the region, and Cranganore remained their spiritual homeland in India. The very last of the Jews had left Cranganore around 1566. By this time, the Portuguese were well established on the western coastline and in Cochin, with ambitions to turn it into the most important trading port in the region. From 1503 to 1663, the Portuguese were the dominant foreign power in Cochin, where the raja remained a titular head. The Portuguese turned out to be cruel overlords, persecuting the Jewish people until the Dutch displaced them, writes Edna.

In the book, ‘The Portuguese and the Socio-Cultural Changes in Kerala 1498-1663’, JAMES JOHN write about the historical account of Kochi that brings Fort Kochi into the light of historical narratives and life through the port. ‘Cochin had a lot of pepper-producing hinterland. Though it was a relatively small kingdom, it used to supply pepper sufficient to load 20 ships every year. When the influence and power of the Portuguese increased by the second half of the sixteenth century, the number of Nairs who got converted to Cochin also increased. It might be because their king was loyal to the Portuguese, and the latter employed many of the former in their service, writes John.

When we go through this fact and historical accounts from different points of view, we understand Cochin’s cultural legacy and diversity route.

Kochi is now regarded as a centre for avant-garde art, heritage tourism, and the creative imagination of Malayali cinema. The “Jew Town” in Mattancherry, Dutch and Portuguese mansions and bungalows, houses of worship like synagogues, churches, and mosques, as well as fishing villages along the coast, have all grown to be popular tourist destinations and artistic motifs used in films and other media. Dutch and Portuguese cultural groups have provided vital support to the Kerala government’s efforts to revitalize the faltering economy of Kochi (the British Raj moved its centres to what are now known as the main metros, such as Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai, and Kolkata).

Kochi-Muziris Biennale

The international festival of contemporary art, Kochi-Muziris Biennale, is one of the new additions to Fort Kochi’s legacy. It takes place in Kochi, Kerala, India. Since its initial introduction in 2012, it has grown to rank among South Asia’s and India’s most prominent art shows. Every two years, for several months, the Biennale is held. It showcases various artworks, such as paintings, sculptures, installations, performances, and new media.

The Kochi-Muziris Biennale frequently employs a variety of locations throughout Fort Kochi, such as public areas, galleries, warehouses, and historic buildings, to display performances and installations of modern art. This blending of art with Fort Kochi’s rich cultural and historical context produces a singular and engaging experience for participants and visitors.

Fort Kochi’s cultural history is a beacon of the past, providing priceless insights into the interdependence of human experiences and the enduring spirit of peace. It challenges us to value variety, honour our shared past, and welcome the benefits of cross-cultural interaction. Fort Kochi reminds us of the value of protecting, honouring, and respecting our cultural legacy for future generations as we traverse the intricacies of our contemporary environment.