Introduction

The world of ‘fine art’, notorious for its elitism, has been much debated. A long history of exclusions and gatekeeping contributed, where only the privileged were allowed the right to produce culture. The idea of ‘fine art’ deemed a vast majority of work as either not possessing any artistic value or not possessing enough worth to find a place among the greats. It is also sometimes overlooked that those behind announcing the greatness of certain works, placing certain pieces in the right collections, or writing reviews for an exhibition are people themselves. They are individuals with lived experiences that colour their understandings of the world. They are not free from bias, collective identities, shared knowledge systems and even prejudice. Curators- as the position they hold in the world of art is formally called- thus, need to be of diverse views to make room for diverse art. In other words, as long as curation is left to the hands of a privileged minority, representation and inclusion shall remain at bay. It is important to then take a closer look at those who decide what ‘fine art’ is, and how this structure has been shifting.

Curation, Disparity and Reclaiming Space

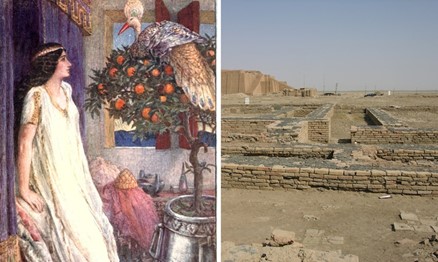

Source: My Modern Met

The earliest curated collection is credited to have been the work of Princess Ennigaldi-Nanna from the Mesopotamian civilisation. A princess of the Neo-Babylonians and a priestess at Ur, her collection from 530 BCE, contained artefacts from between 2100 BCE to 600 BCE. They were arranged, well kept, and labelled in three languages-often assumed to have been done by the princess herself. Her father, too, was known for his contributions to preserving texts from across the land. Though the earliest example of curation and recognition of art in gallery spaces seems to have been done by a woman, the field later evolved into one dominated by men. Even today, the high number of women students does not reflect in the number of professionals holding titles. Additionally, with the world’s Eurocentric approach to art and rooted patriarchy, the white man often appears to be a regular holder of this position.

Source: ARTnews

Yet, the world has seen change over the last century- many voices have fought for recognition as active participants in the movement to celebrate art, those that were initially excluded. This has in turn allowed room for artists who did not fit the convention years ago- not only due to their skills but also due to the social identities they carried. Women curators have been among the earliest to recognise and shift the narrative- introducing themes that the world could not digest previously and making space for new artists. Marcia Tucker, for example, founded the New Museum in New York in 1977. With its higher focus on new media of art and artists, it paved the way for new talent and topics of discussion in art. Artists like Ana Mendieta, Nancy Spero and others had their solo exhibitions here, and thematic presentations, such as “Difference: On Representation and Sexuality” too, are part of the museum’s history. Important shifts in policy too, may be a result of wider perspectives by curators. Upon becoming the first director of what would go on to become the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 1935, Grace McCann Morley made the decision to keep the institution open until 10 p.m. Unusual and revolutionary, the move made art accessible to a wider working population and helped increase the popularity of fine art through accessibility.

Source: ARTnews

Curators who are People of Colour have made extremely important contributions to the field of art- from preservation to gaining the same status, and recognition for the work done by their communities. Bisi Silva, a curator and founding director of the Center for Contemporary Art, Lagos, Nigeria has done prolific work in the field. The CCA promoted experimental art, workshops, and hosted artists like El Anatsui and J. D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere. The centre also has a library that carries 1000 volumes on African art history. Her work in Dak’Art Biennial of Contemporary African Art in Senegal and the Thessaloniki Biennale in Greece reflect her aims to, “give access to information that could lead to meaningful dialogue, exchange, and collaboration”. Native American art and its conservation too have reclaimed their deserved space in the world of art due to the involvement of Native American curators. Patricia Marroquin Norby (Purépecha), became the first person of indigenous descent to be hired as a curator at the Metropolitan Museum in 2020. With a Ph.D. in American Studies and deep knowledge of Native American art, Norby brings an important perspective to works that have been historically suppressed in the history of the United States. Additionally, the organisation “UCROSS” has been organising the Native American Art Curatorial Convening (NAACC) which has included several important curators of Native American Art, who have indigenous roots themselves.

Source: The New York Times

Queer artists and curators have also been creating spaces for their art- that features the themes of identity, exploration, sexuality and thinking beyond the binary. One of the many significant change-makers in the field of Queer art is the organisation “Queer|Art” which features Queer artists from all walks of life and hopes to combat the loss of Queer artists to the AIDS crisis that has left an entire generation of creators and Queer people without mentors.

Source: The New York Times

So, How Does it Look Like?

The power curators hold in the field of art essentially allows them to decide what is worth discussion, proliferation, and status. It needs to thus, be stressed that this power needs to be made accessible to individuals of all communities- particularly those that have been strategically oppressed and sidelined throughout history. However, this change has been gradual and one that has been fought for across centuries- it is not to imply that the world of fine art is as accessible and accepting as it should be yet. Elitism, denial of resources, racism, classicism and casteism all work hand in hand to systematically deprive communities of the spaces they have long deserved. While collections and exhibitions of art by artists have been created and displayed, members of many communities being able to occupy positions like that of curators are still rare. Around the world, art is still measured on scales of historic worth, assessed on age-old notions of greatness- change in narratives, as seen in the above cases, can only happen with a redistribution of power and answering the question that remains significant to date- which stories make history and who makes this decision?

SOURCES:

- The Conversation: Hidden Women of History Ennigaldi nanna curator of the world’s first museum

- ARTnews: 20 Curators Who Changed the Way We See Art

- Queer art.org

- metmuseum.org: Patricia Marroquin Norby

- ucrossfoundation.org: Native American art curatorial convening

Read Also:

Contributor