19th Century Art and Honoré Daumier

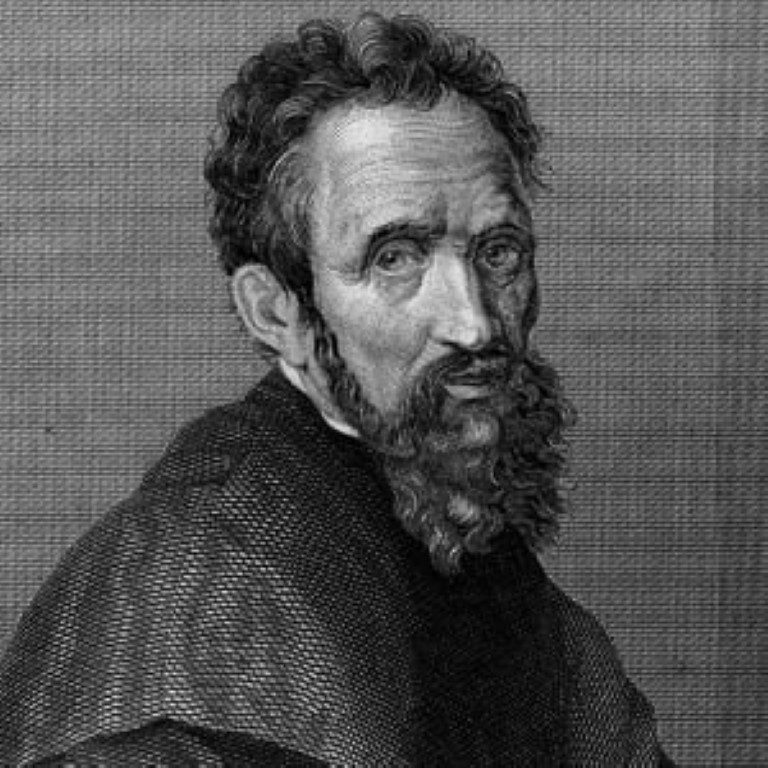

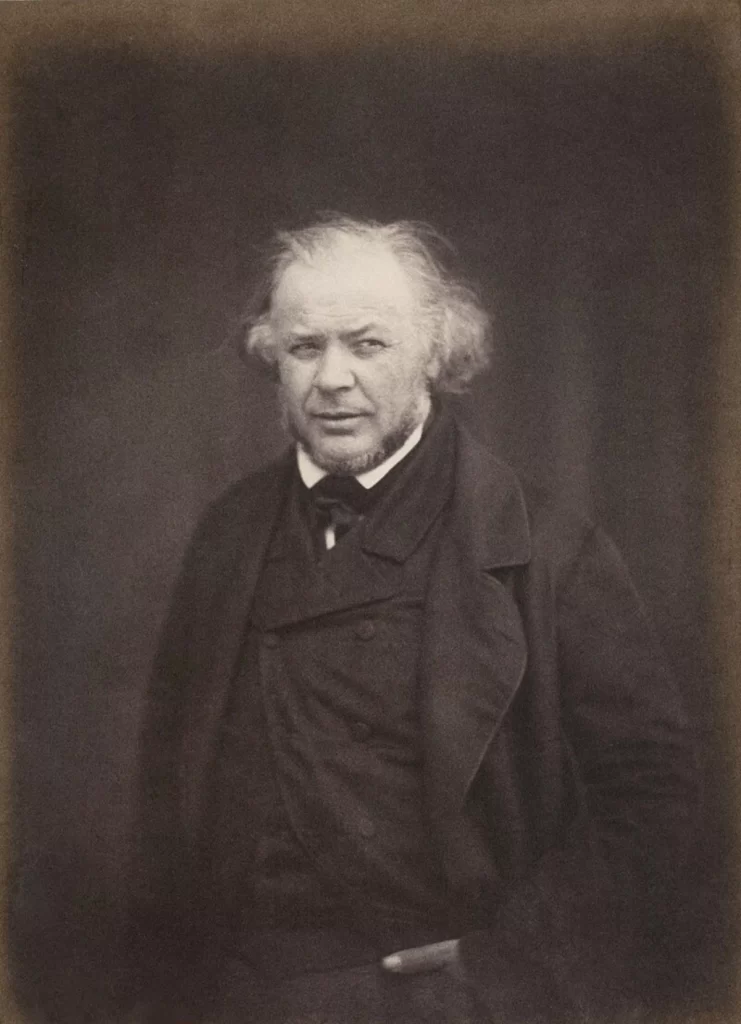

Honoré Daumier was a prominent 19th-century, who was born today, on 26th February 1808. The protagonist of French realism, he was an artist and printmaker, who was known for his political caricatures. With his sharp wit and acerbic humour, Daumier mounted scathing attacks on the corrupt ruling establishment and made incisive commentaries on contemporary socio-political issues through his satirical lithographs.

Daumier Caricatures A Mirror of The Despicable Political Ground

Let’s try to understand the political context in which Daumier caricatures grew to be so fondly peeped through. The French Revolution of 1830, also known as the July Revolution, was the second revolution to rock the country after the French Revolution of 1789. It was a reaction to the ineptitude of the ruler Charles X. People took to the streets and barricades were set up by workers, students and ordinary citizens. The revolution, which lasted for only a few days, ended with Charles X abdicating his throne and Louise-Philippe being named the new king.

The July monarchy, as the new ruling establishment was called, was marked by a shift of power from the landowning aristocracy to the wealthy bourgeoisie. Though Louise-Philippe was known as the “citizen king”, he remained ignorant of the demands of his people. Even though his constitutional charter promised a free and liberated press, he soon passed draconian laws that made criticism of the monarchy treasonous. This had a humungous effect on the 19th-century French art.

Daumier’s art emerged in the Parisian caricature scene in 1829. A republican democrat belonging to the working class, he soon turned into a fierce critic of the government’s policies which only benefited the wealthy bourgeois class. He joined arms with Charles Philipon, a publisher of humorous political journals, and began creating politically charged caricatures, attacking the bourgeoisie, the church, the judiciary, politicians and the monarchy.

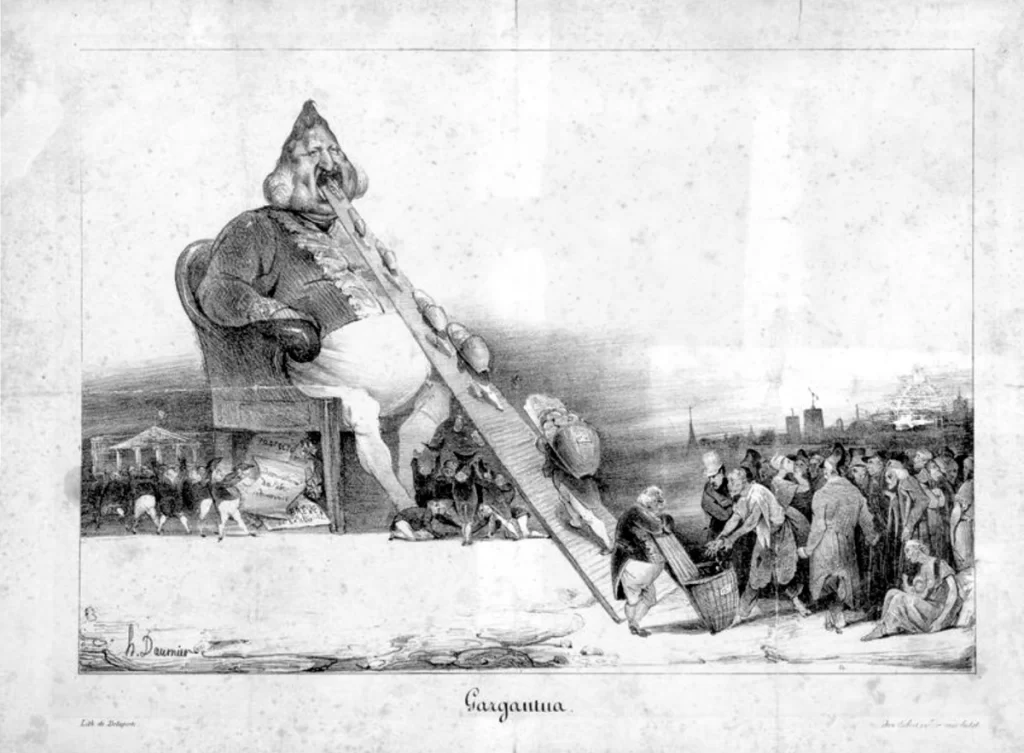

Gargantua (1831)

Honoré Daumier’s first run-in with censorship laws occurred in 1831 – just a year after he seriously started producing caricatures – owing to his searing critique of the July monarchy, Gargantua (1831). The lithograph represented King Louis-Philippe as the obese giant Gargantua, a character from François Rabelais’ series of novels Gargantua et Pantagruel (1532-35). In this Daumier caricature, the poor are shown handing over their meagre wealth to ministers, who carry them across a diagonal plank and feed the ravenous monster, in an unending queue. The king is also shown ‘defecating’ letters of appointments and nominations for his favourites. Daumier lambasts the corruption of the monarchy and the exploitation of the working class through this work. Soon after Gargantua was published, Daumier was brought to trial for his ‘treasonous’ activity and handed a prison sentence. Although several of his lithographs were censored throughout his career, this was the only time Daumier was incarcerated for his political caricatures.

Courtesy – Wikimedia Commons

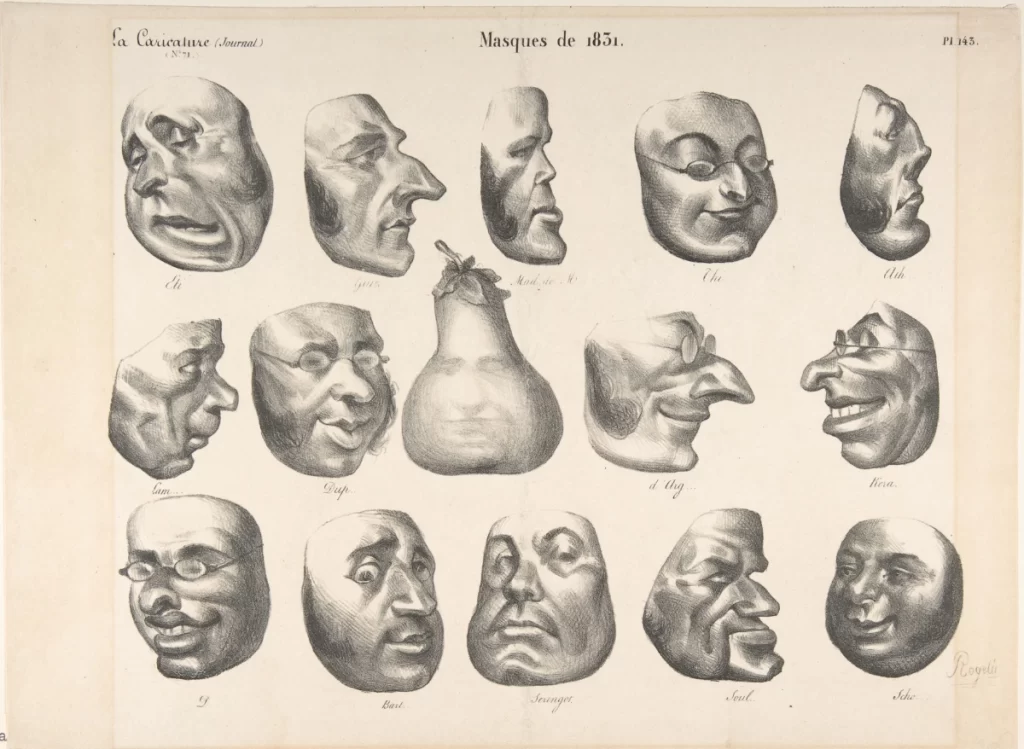

Masks of 1831 (1832)

His lithograph Masks of 1831 (1832), published in Philipon’s journal La Caricature in 1832, depicts portraits of fourteen parliamentary delegates from the Chamber of Deputies, arranged in three rows. Based on actual politicians, these Daumier caricatures deliberately distorted and exaggerated their physical features to poke fun at them. Interestingly, Daumier presents their visages as ‘masks’, hinting at their deceitful nature. Occupying the central position is a bloated representation of King Louise-Philippe’s face in the shape of a pear. This was a blatant insult owing to the slang meaning of the word – a moron. Daumier would use the pear imagery to portray the ruling monarch in several other works, including Gargantua.

Courtesy – The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Court of King Pétaud (1832)

In The Court of King Pétaud (1832), Honoré Daumier satirises the French legal system. The lithograph portrays a group of judges in the court of King Pétaud, who was known for his incompetence and inanity. The judges are depicted as a group of buffoons engaged in a frivolous and absurd trial, painting an accurate picture of the corrupt and inept justice system of the time.

Courtesy – Daumier

Rue Transnonain, April 15, 1834 (1834)

Rue Transnonain, April 15, 1834 (1834) was a response to the massacre that took place in the Rue Transnonain, a working-class district in Paris, during the early days of Louis-Philippe’s reign. On the night of April 14, 1834, soldiers from the National Guard barged into a working-class apartment building at the corner of two streets – rue Transnonain and rue de Montmorency – and began indiscriminately killing clueless residents, including women and children. Earlier that day, a shot fired from the top floor of that building had killed a well-known army officer during protests that had erupted in Lyon and Paris following the passing of a law.

Courtesy – The Metropolitan Museum of Art

This 19th-century French art lithograph presents the horrific aftermath of the massacre – a man lies dead in the middle, over the corpse of his baby, while the body of his wife lies to the left and the right, perhaps, his elderly father. The harrowing scene offers powerful commentary on the violence and oppression inflicted upon the working class by the government. Daumier was inspired by Francisco Goya’s work on a similar theme, The Execution of the Rebels on the Third of May, 1808 (1814).

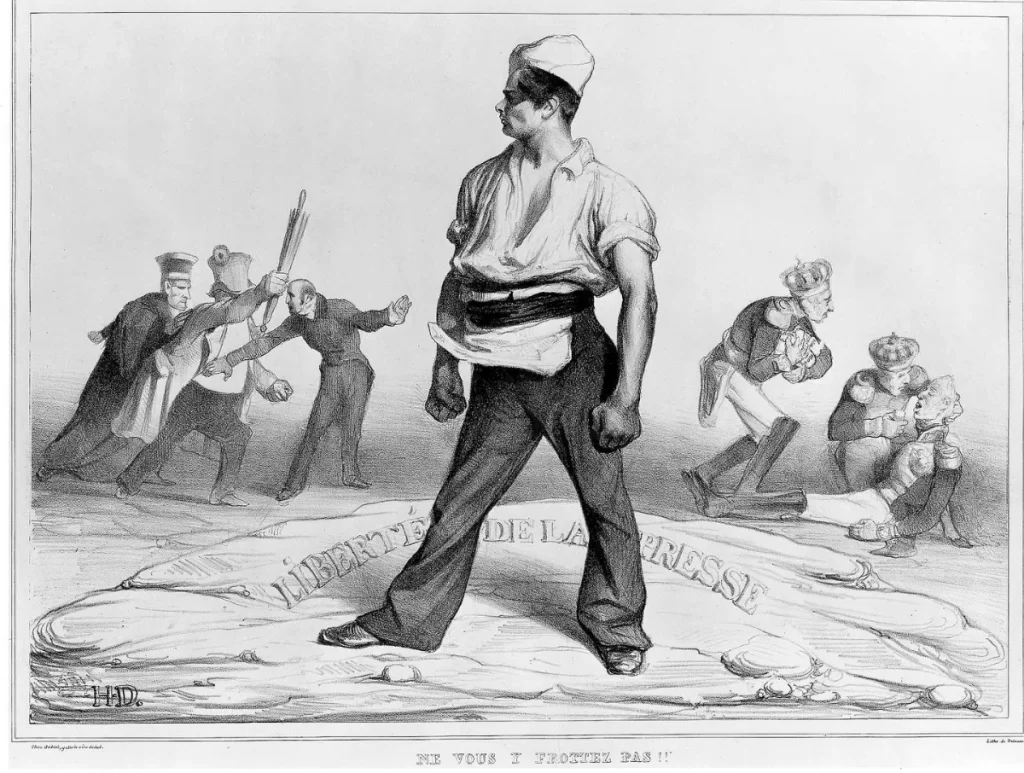

Don’t Meddle with the Press! (1834)

Don’t Meddle with the Press! (1834) is another of Daumier’s caricatures which asserts the power of the press, while addressing the issue of censorship and the muzzling of freedom of the press. A young printer, personifying the press, is shown to be defiantly standing, while the fallen King Charles X is attended by foreign monarchs carrying bags of money. The lithograph is a powerful reminder of the importance of a free press and the dangers of government censorship.

Courtesy – MFA Collection – Museum of Fine Arts

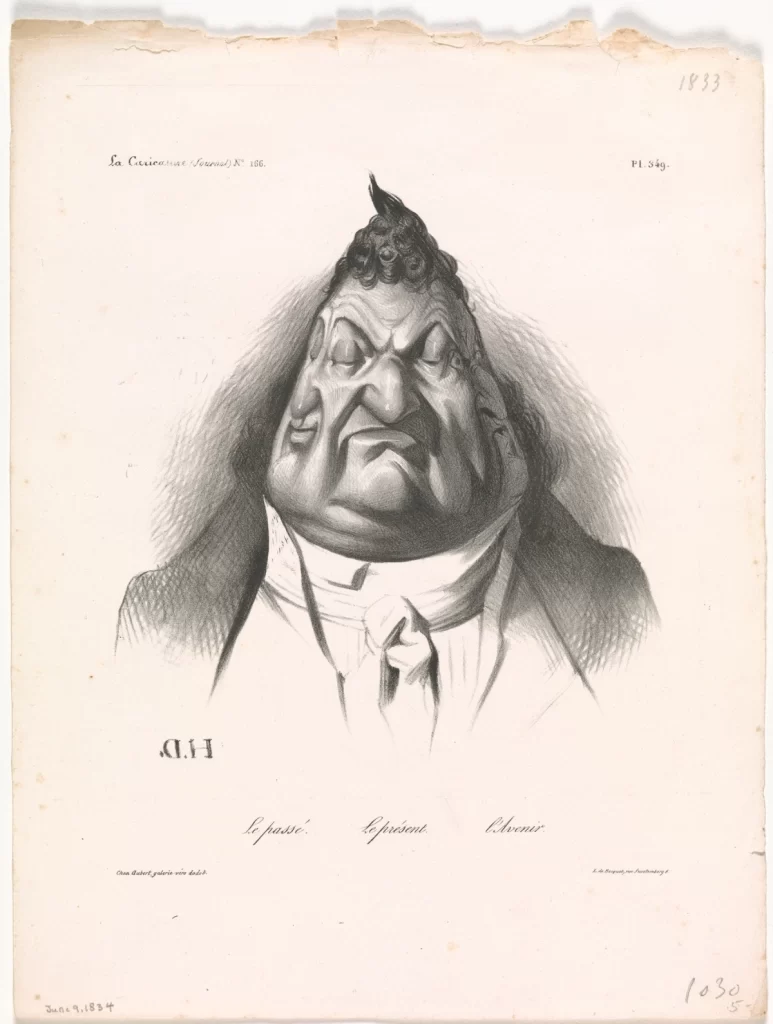

Past, Present, Future (1834)

Past, Present, Future (1834) is another lithograph which highlights the growing tension between the ruling class and the working class. The image portrays three figures representing the past, present and future of France. The past figure is depicted as a wealthy aristocrat while the present figure is a soldier. The future figure, on the other hand, is represented as a working-class labourer. This particular Daumier art wanted to address the changing social and economic landscape of France.

Courtesy – The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Political Honoré Daumier’s caricatures continue to remind us of the power of art as a vehicle of protest in today’s times when government clamp-downs on journalists and curbing of free speech are still rampant across the globe.

References

- Elizabeth C. Childs, ‘Big Trouble: Daumier, Gargantua, and the Censorship of Political Caricature,’ in Art Journal, Spring, 1992, Vol. 51, No. 1, Uneasy Pieces (Spring, 1992), pp. 26-37.

- https://www.thecollector.com/honore-daumier-realist-lithographer/

- https://smarthistory.org/daumier-rue-transnonain/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Honor%C3%A9_Daumier

- https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/collection/works/DO33.1967/#about

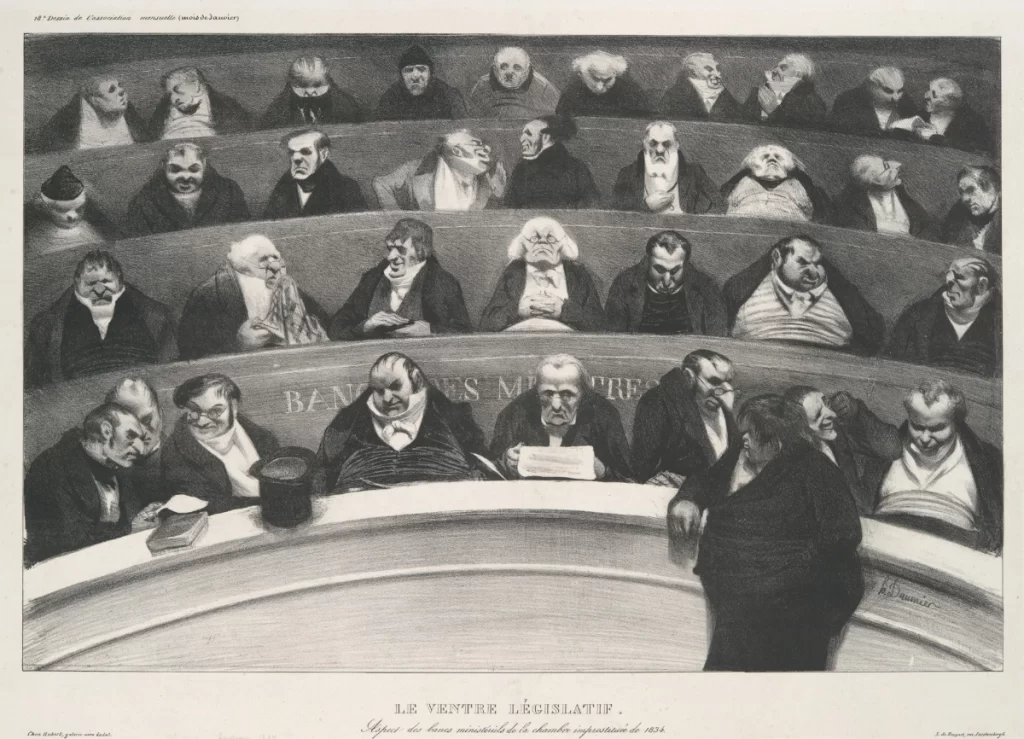

Image – Le ventre législatif (1834). Courtesy – The Metropolitan Museum of Fine Art

Contributor