Smriti Mahotra

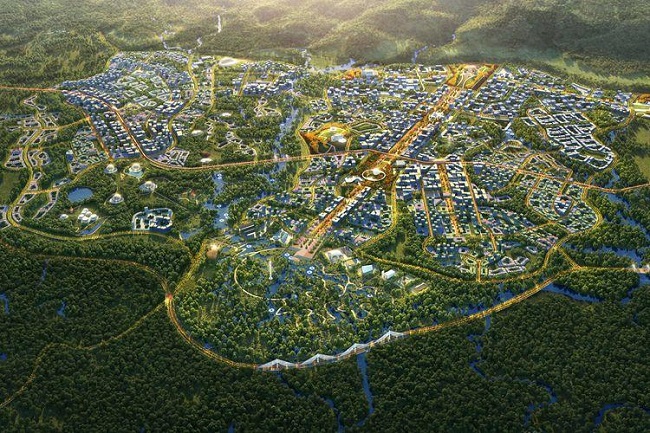

Nusantara, Indonesia’s groundbreaking new capital, epitomises President Jokowi’s ambitious vision for a future characterised by sustainability, inclusivity, and economic vitality. Positioned strategically and designed to be environmentally conscious, Nusantara is poised to become a global exemplar of intelligent and eco-friendly urban development. With its focus on creating a livable environment, robust infrastructure, and a thriving economy, Nusantara aims to attract talent, foster innovation, and drive sustainable economic progress. As Indonesia readies itself to host the G20 and the B20, Nusantara will serve as a model for sustainable energy transition, digital transformation, and collaboration in the realm of greener infrastructure. This transformative endeavour establishes Indonesia as a trailblazer, harmonising economic growth with environmental stewardship and ensuring inclusive prosperity. As Nusantara assumes its place on the global stage, it carries the promise of a future where sustainability and innovation walk hand in hand, forging a brighter tomorrow for Indonesia and inspiring nations worldwide.

Indonesia’s ambitious plan to establish a new capital city, Nusantara, is making significant progress. Stage One of the project, including important national institutions, is set to open on Independence Day in 2024. The city’s design is focused on sustainability, with a remarkable 70 percent green space and 100 percent renewable energy. Autonomous electric vehicles will provide public transportation, and a portion of the land will be dedicated to food production using recycled wastewater. While private investment is crucial to fund most of the development costs, there are concerns about the project benefiting wealthy individuals with land interests in the area. Nonetheless, Nusantara represents Indonesia’s commitment to inclusive and eco-friendly development, with President Jokowi aiming to set an example for other nations. The successful completion of Nusantara will redefine Indonesia’s political and development landscape, showcasing the nation’s dedication to progress, equity, and environmental stewardship.

Researchers from the University of Indonesia, the Indonesian National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), and the University of Queensland have conducted on-site visits to Ibu Kota Nusantara as part of a research collaboration. They aim to examine the social and economic impacts of the new capital city on the local population. Challenges such as increased pressure on infrastructure, especially water supply, and growing disparities in land ownership and acquisition are key concerns. The research findings will provide insights into these issues and help ensure a balanced and equitable approach to the project’s development.

The most urgent concern surrounding the development of Ibu Kota Nusantara is the issue of land rights and tenure. The designated site for the new capital city is currently inhabited by approximately 20,000 people, who occupy 40 percent of the land area. This includes indigenous groups and migrants who have settled in the area over the past 50 years due to logging activities. Land grabbing and marginalisation have been ongoing issues in this region, with industrial forestry operations and concessions exacerbating the situation.

To expedite planning and development, Ibu Kota Nusantara has been granted the status of a National Strategic Project, which diminishes the power of local and provincial laws and regulations governing the area. The recognition of customary land ownership, protected under traditional laws (Masyarakat Hukum Adat), has become uncertain as new political and regulatory constraints come into play at the district level. While national regulations provide for the recognition of traditional land ownership, the implementation process within the Ibu Kota Nusantara zone remains unclear. This poses challenges for traditional land claims within the project area, as resistance and representation for indigenous communities become more difficult in national regulatory environments.

NGOs supporting local communities have expressed concerns that the rapid implementation of this National Strategic Project has overlooked the existing local institutions responsible for managing and recognizing land tenure, particularly for traditional owners and marginalised groups. Indigenous groups, such as Paser Balek, Tonyooi, Semoi, Mentawir, Pemaluan, Maridan, Basap, and Kenyah Lepo Jalan, attended a workshop on participatory community mapping of customary areas in November 2022. These groups are at risk of eviction from their ancestral lands or indirect impacts from the infrastructure development associated with Ibu Kota Nusantara. Despite the efforts of NGOs, there is uncertainty about the protection of these groups’ interests. The complex history of land claims based on origin narratives further complicates the situation. While national-level regulations allow for the formal recognition of customary forest areas, the process requires legislative support from district-level governments, which may face political and regulatory obstacles. The bypassing of these requirements by the National Strategic Project mandate makes it difficult to establish land rights. Moreover, competing claims by different indigenous groups add additional complexities, making it challenging for external parties to determine the validity of claims, and consultation with the groups themselves has yet to occur.

Overall, the accelerated pace of the National Strategic Project raises concerns that local institutions and communities managing land tenure have not been adequately considered, jeopardising the interests and rights of indigenous and marginalised groups.

Another group with a claim to the land in the project area is the transmigrants, primarily from Java and Sulawesi. These individuals relocated to the region as part of the government’s transmigration program during the New Order era, starting from 1979, in an effort to alleviate population pressure. Transmigrants were granted land, often displacing traditional landowners in the process. Over the past 40-50 years, these transmigrant communities and their small-scale agricultural activities have become well-established. Unlike the hereditary claims of indigenous groups, transmigrants have a clearer legal claim to the land they currently occupy.

Additionally, there are both transmigrant and indigenous communities residing within concessions owned by industrial plantation operators and wealthy corporations based in Jakarta. These concession holders permit certain portions of their land to be occupied by these communities as they rely on their labor for forestry and palm oil operations.

In summary, there are three main groups asserting claims to the land in the project area: indigenous groups with hereditary claims, transmigrants who were allocated land during the transmigration program, and communities residing in concessions owned by plantation operators and Jakarta-based corporations. Each group has its own unique circumstances and legal standing concerning land ownership and occupation.

The announcement of the new capital site in 2019 led to a surge in land values, making land compensation negotiations complex. The Indonesian government implemented a land freeze to curb speculation, but it has not stopped illicit deals by influential corporations known as the “land mafia.” Locals fear that the freeze will benefit large developers at the expense of small, local ones, and hinder compensation efforts for existing residents. Additionally, permits granted to local developers are being overturned in favour of national-level developers, causing concerns among small developers who feel overpowered.

Even for those who can afford to wait out the land freeze – among them farmers and other small landholders – are ambivalent about expected windfall profits. They fear compensation payments will not cover new land purchases and business re-establishment costs for sites anywhere close to where they are operating now. The head of one village in the current IKN development zone told us that any compensation they had been promised would not reflect the speculative increase in land values that had taken place since then. Several village heads spoke of the unhealthy ‘rumour mill’ about IKN that had developed in the absence of genuine consultation from the national government.

Meanwhile, those on the fringes of the development zone, who were confident they would remain in their villages, were optimistic about the economic development and employment opportunities the IKN would bring. IKN would put them ‘on the map’, bringing paved roads, new retail opportunities, services and infrastructure such as healthcare. However, they were already seeing the negative effects of large numbers of imported construction labourers on the ‘moral fabric’ of the local communities, as they witnessed the arrival of alcohol, drugs and sex workers.

Beyond all these issues, locals tended to think construction would go ahead despite any objections they might have. Despite (or perhaps because of) the enormous scale of the project, there has been minimal consultation or information from planning authorities with local stakeholders. Local informants agreed that the establishment of the new capital was hostage to politics. At the same time, they recognised that the politics themselves are uncertain. While many welcomed the improved infrastructure and economic activity that new migrants to the city would bring, there was caution about whether the project would survive Jokowi’s tenure. Since the fall of Suharto in 1998, Indonesian presidents have been limited to two terms. Jokowi will step down at the end of 2024 following the February election. His ambition is to officiate at the inauguration of the initial zone on 17 August 2024. Few of those we spoke to disagreed that Nusantara can relieve pressure on a climate-threatened, overcrowded, gridlocked Jakarta. But everyone acknowledged the project was political – a ‘Presidential legacy’. If one of the presidential candidates in February 2024 campaigned hard to oppose it, it could be derailed.