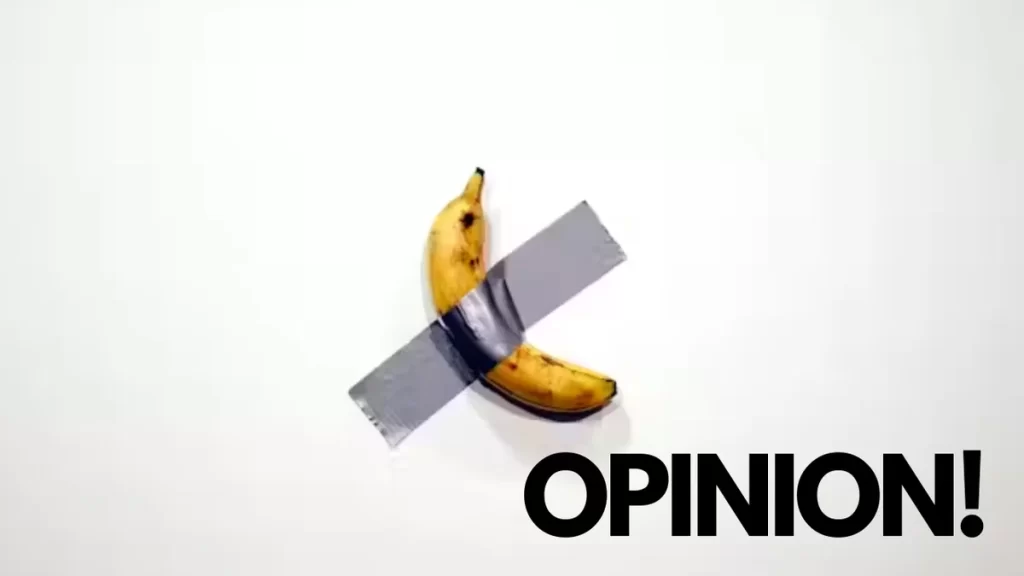

Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian, a conceptual work consisting of a fresh banana duct-taped to a wall has made headlines as one of the most polemic works in contemporary art. First shown at Art Basel Miami Beach in 2019, it soon sparked discussion about art’s nature and value. The work sold for $150,000 at its debut, an eye-popping price for what seemed to be a quotidian object. The controversy returned in November 2024 when the cryptocurrency entrepreneur Justin Sun bought it for an astonishing $6.2 million at a Sotheby’s auction, then ate the banana during a press event. Not only did this act emphasise the transitory nature of the piece, it reinforced its dependence on conceptual rather than material value.

Part of what makes Comedian so intriguing is its simplicity and absurdity. On its face value, though, it’s hard to get how a banana and a strip of duct tape could be worth millions. The key is deciphering the conceptual underpinnings of the artwork. It isn’t the piece’s physical elements, which are perishable and replaceable, that buyers are purchasing; they are purchasing the access to the intellectual property and to the artist’s vision. Included in the sale is a Certificate of Authenticity and detailed installation instructions, which include the exact height and angle at which the banana must be taped. These guidelines are crucial to preserve the very soul of the artistry. The true art exists in the idea, an ephemeral construct beyond the material banana plastered to the wall.

This idea goes against traditional definitions of art. Art has historically been connected to craftsmanship, permanence and a visual aspect. Comedian upends these conventions, compromising the banal with an intellectual payload. The piece raises questions: What constitutes art? Is an object required to be unique, beautiful, or skillfully made to have artistic value? Conditions of Materiality: Can there be an art that is only an idea, separate from its material existence? The act of forcing viewers to grapple with such questions turns Comedian into a critique of the art world’s established conventions.

But the astronomical price of the artwork also sheds light on the art market’s dynamics. Cattelan’s image as a provocative and powerful artist is a major reason for Comedian’s value. His earlier pieces, like America, a solid gold toilet, and La Nona Ora, a statue of Pope John Paul II struck by a meteorite, have secured his legacy as a master of irony and satire. The artist’s renown imbues Comedian with more than its conceptual merit, and collectors would just as soon have it as a sign of status. And its scarcity, only three official editions were created, along with two artist proofs, further fuels its appeal, tying it to the art market’s fixation on exclusivity.

As if its prestige were not already enhanced enough by Comedian ’s debut venue, Art Basel Miami Beach. Art Basel means high-stakes art transactions which wealthy collectors may see as speculative investments in contemporary art. The price at which it was paid for Comedian not only reflects the market value of its concept, but also the “trading” psychology, which turns art into a commodity. Owning such a widely known piece adds cultural capital, transforming the buyer into a player in a broader cultural phenomenon.

Comedian, for all its provocation, holds up a mirror to the limitations of conceptual art. Though it does well to critique the excesses and absurdities of the art world, it leaves out broader societal issues. It could have been, let us say, a symbol for labor exploitation in agriculture, consumerism or global inequality: a banana, after all, is also an everyday object. Ultimately, this dislocation from irony prevents this piece from exploring the collective fragility of being human. Its humor and absurdity raise issues to ponder without cultivating an empowering or optimistic perspective.

This tension between irony and sincerity in Comedian is symptomatic of postmodern art in general, which tends to critique dominant systems without proposing new ones. Although Cattelan’s work is undeniably clever, the emotional resonance it lacks makes it all the more so, keeping it from elite criticism of the art market, and in turn, the wider world as well. At its best, the piece flickers between genius and jadedness, forcing the audience to grapple with what its actual effect is. Comedian is as much a barometer of the art world’s foibles as a product of them. What makes it valuable is not the banana or the duct tape but the conversations that it generates around art, value and meaning. Masterpiece or madness, it demands we examine our ideas about creativity and the systems that govern it. And although it doesn’t provide answers, it gives us questions that echo long after the banana has come off the stand or been eaten.

Iftikar Ahmed is a New Delhi-based art writer & researcher.