Marino Marini’s Modernist Transformation

Marino Marini transformed Italian sculpture through his distorted visions only in a way a true modernist would; radically transforming something without a care for the past or the traditions it holds. He was born today, 27th February 1901. Marini was one of the most celebrated Western sculptors of the 20th century and greatly influenced the Italian modernist movement, as the country was struggling with a rise in fascism. His works also exhibited an Etruscan art influence.

Courtesy – Wikipedia

He was an integral part of the avant-garde movement and having spent some time in Paris in the 1920s, he was acquainted with Picasso and Braque. He received formal artistic training at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Florence, where he would later accept a professorship. He opened his studio in Florence in 1924. The ongoing struggle in the first half of the century to represent the rapidly transforming and war-stricken world in front of his eyes drove Marini to embrace unorthodox and bizarre forms of figurative sculptures and art. Marino himself describes the change:

Not so long ago a sculptor could still be content with a search for full, sensual, and vigorous forms. But in the past fifteen years [1943 – 1958], nearly all our new sculpture has tended to create forms that are disintegrating.

Themes in Marino Marini’s Sculptures

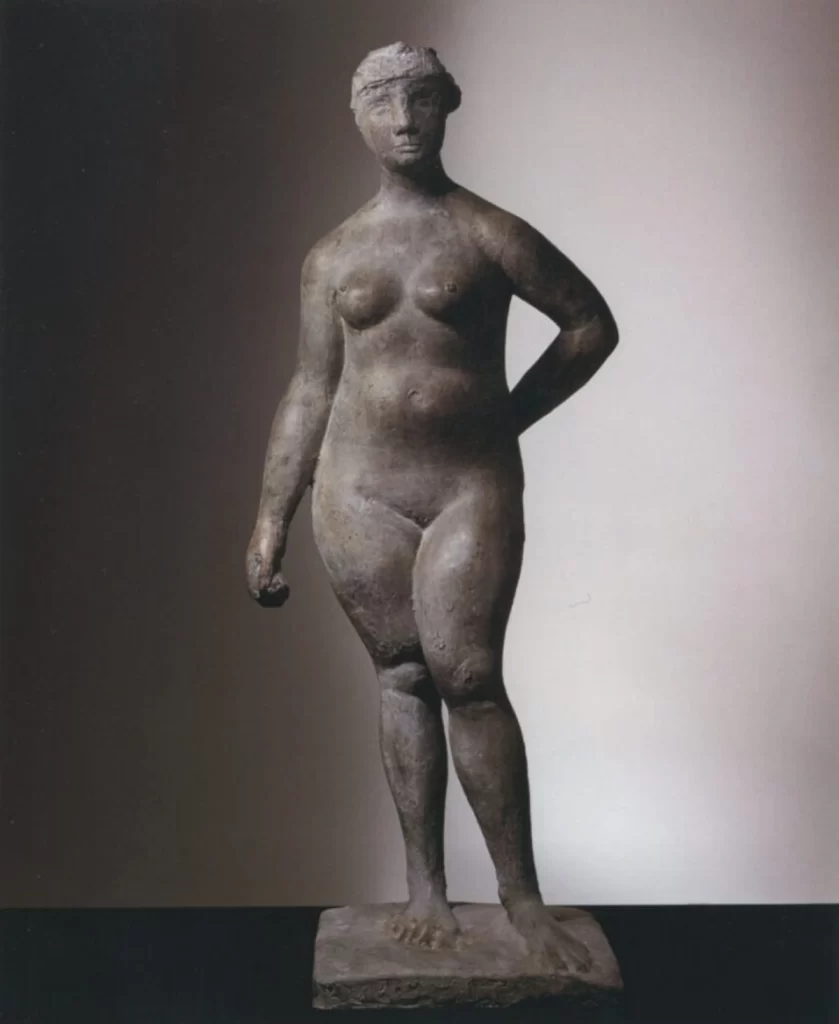

His modern sculptures and paintings challenged and tried to deconstruct strict anatomical figures and engaged in an interrogation of the absurd and the exaggerated. Marini is well known for deconstructing the idea of the female nude, breaking it down to absurdly fantastical proportions in his various bronze sculptures, notably in Pomona.

Courtesy – Roslyn Bernstein via Medium

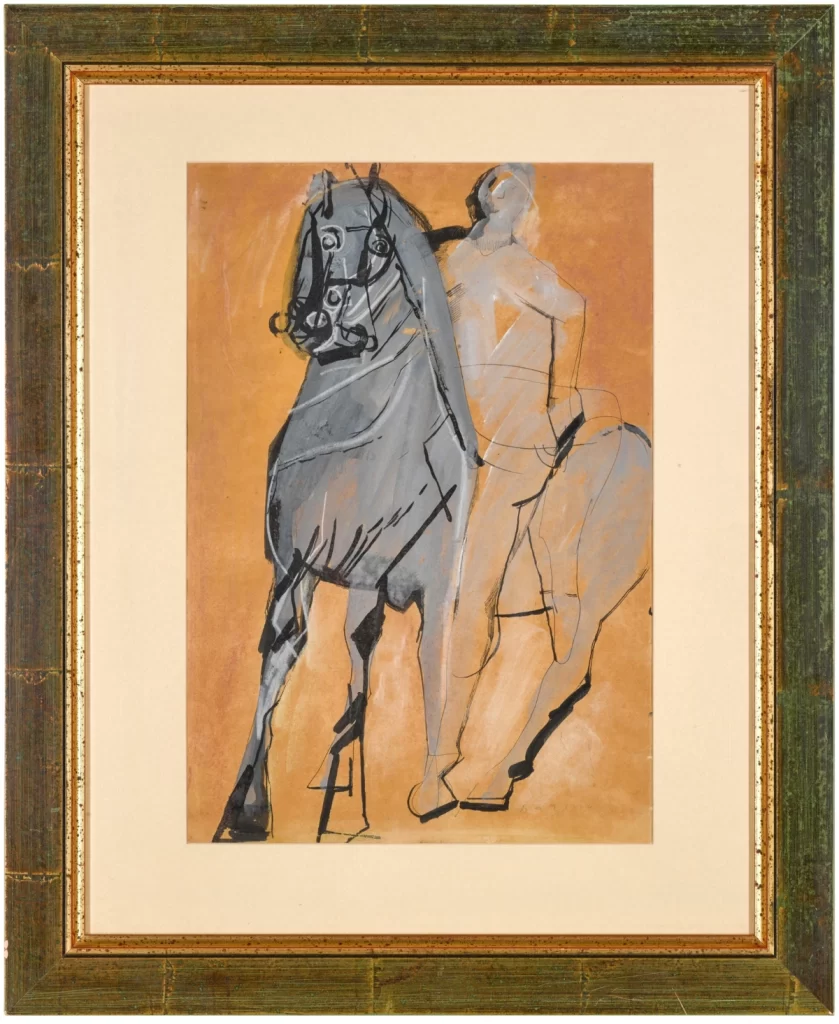

Another key theme in Marino Marini’s work is that of the Etruscan art influence and the subsequent figures, focusing on the horse and the rider as they unnervingly hold their place in his sculptures. Critics have noticed that Marino’s work bears an inherent contradiction; that is, it is both abstract and historicist. The base of Marini’s style takes inspiration from the classic Roman, Etruscan, and early Renaissance works, but he transforms the classical bronze sculptures into something bizarre and extraordinary.

Marino Marini’s Equestrian Desires

A figure that Marino keeps revisiting in his career is the equestrian figure, typically representative of resplendent glory and heroism. Equestrian statues have been a staple of Ancient Rome, and are typically used to commemorate military leaders with great victories or stellar leadership. This motif returned to Europe during the Renaissance and dominated Italy through the sculptures of Donatello, The Equestrian Statue of Gattamelata (1453) and Giambologna, The Equestrian Monument of Cosimo I (1594). Marini himself notices the purpose served by these equestrian statues, saying that throughout the centuries they imbue an epic purpose, exalting triumphant heroes. According to him,

In the past fifty years, this ancient relation between man and beast has been entirely transformed. The horse has been replaced, in its economic and its military functions, by the machine, by the tractor, the automobile or the tank.

gouache, pen, ink and pastel on paper.

Courtesy – Sotheby’s

The artist best explains the agony that went into the creation of these bronze sculptures:

My equestrian figures are symbols of the anguish that I feel when I survey contemporary events. Little by little, my horses become more restless; their riders less and less able to control them. Man and beast are both overcome by a catastrophe similar to those that struck Sodom and Pompeii. So I am trying to illustrate the last stages of the disintegration of a myth, I mean the myth of the individual victorious hero, the ‘uono di virtù‘ of the humanists.

L’angelo della città (1948)

The horse with the rider is distorted in Marini’s works– the functional relationship between the leader who controls the horse and commands his populace no longer retains itself in the post-war era. Under the shadow of dictators like Benito Mussolini, the age-old figure of the heroic comes undone. Marino’s early equestrian works still retained some structure and had a sense of poise (though this was also charged with potent meaning).

Courtesy – Canal Grande

Marino’s most recognizable bronze sculpture, L’angelo della città (1948) or The Angel of the City showcases this evolution. The neck of the horse becomes indistinct from its head, and directly within the line of sight is the phallus of the horse rider, who has his arms spread apart, looking at the sky. The two figures appear perpendicular to each other and the final product evokes an uneasy sense of despair.

Miracolo (1959-60)

The riders and horses become more and more distorted and demented in Marino’s works as time progresses. This can be evidenced in his sculpture Miracolo (1959-60). Both the horse and the ride have obtained exaggerated and elongated forms, they are slouched down in opposite directions, almost blending in with the ground and lacking distinctive heads. The rider in the modern sculpture lies prostrate on the back of the horse, in a pose that assumes senselessness.

Courtesy – Wikimedia Commons

Pomona (1935-1950)

Marino Marini also created the image of the Etruscan deity, Pomona. Between 1935 and 1950, he created multiple etchings, paintings, and bronze sculptures of the goddess with Etruscan art influences. Suffice it to say, some were more graphic than others. Pomona represented fertility for the Etruscans. For the borrowed Roman culture, she became the goddess of fruit, tasked with protecting their orchards. Marini viewed them through the lens of early Italian classicism. Although in conventional iconography, Pomona is seen holding an apple. However, Marini’s vision, intentionally leaves out the apple, equating Pomona with divine femininity.

Bronze, 162x66x53 cm.

Courtesy – Olla Art

He described his Pomona as a unique enigma. At times, Marini infused a playful and anachronistic touch into his modern sculpture. Upon further examination, you would realise that his Pomonas dons a watch, ring, and bracelet. He says,

My Pomonas live in a bright and sunny world of poetry, humanity, abundance and great sensuality. They represent a happy season, broken by the tragic times of war. In all of these images, femininity is explored in its most remote, inescapable and mysterious forms: it is a type of unavoidable necessity, static immovability, and primitive and unconscious fertility.

Conclusion

Marino Marini unhesitatingly takes several classical motifs and styles beloved by the Italians, the historic by-products of the Renaissance, and interprets them within his own modern and contemporary contexts. As Marini mentions, it is impossible to go back to the past, the so-called “golden age”, and like every Modernist, he sought drastically different forms of representation, and all his artistic products were brittle and broken in ways, slowly disintegrating the structural integrity of the traditional forms with figurative sculptures.

Image – Horse and Rider (1951). Courtesy – Flickr