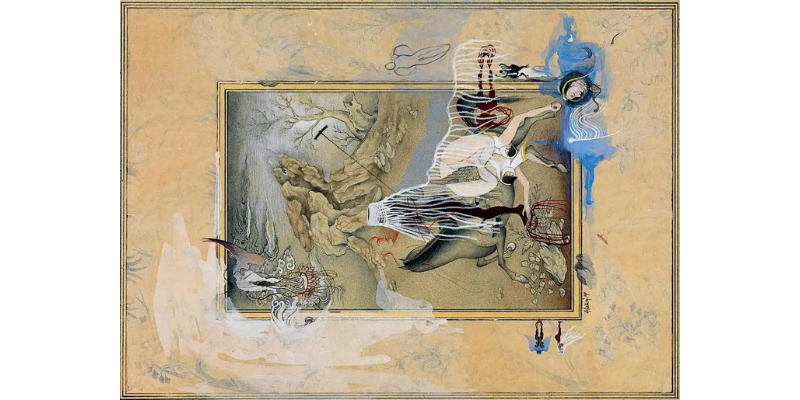

Once Dr. B. N. Goswami showed me a catalogue of an exhibition of miniature artists from Lahore, showing in New York. He was enamoured of the strides taken by the modern miniature artists from the National College of Arts, Lahore, especially by the works of Shazia Sikander. The catalogue exposed me to an altogether new iconography; the idiom used by the miniature artists to express contemporary themes was, of a different order.

An art historian, Dr. Goswami was also keen on the evolution of miniature art beyond its survival as a classical art, in India. However, many families in Rajasthan continue to produce works of miniature art that are usually bought by tourists or rich patrons. These painters rarely deviated from the themes and styles of the past. New motifs and styles are often not welcomed by the buyers. And the artists cater to their demands.

He had perhaps these issues in mind when he set out to introduce miniature art, as a subject for the students of Master’s in fine arts, at Punjabi University, Patiala. It was the first in North India. None of the art colleges teach miniature art as an option for painting courses. The then VC of Punjabi University, Dr. Swaran Singh Boparai had great regard for Dr Goswami’s vision; he ensured that his proposal did not face any hurdles.

In 2006, Punjabi University started the course in miniature art, as an optional subject. Goswami persuaded the famous miniature artist of Jaipur, Dr M K Sharma, known as Sumahendra in the art circles, to extend his teaching services to Punjab, since he was the former principal of Rajasthan School of Art, Jaipur. Dr Sharma started visiting Patiala and stayed for two weeks in a month. Goswami too used to deliver a lecture, once a week on art history.

Dr Boparai resigned in 2007. This affected the facilities the course was receiving. Dr Goswami stopped visiting the university. Dr M K Sharma continued to visit the university till his demise in 2012. Thereafter, it has been an odd contractual faculty or other, pulling along the course. The present head of the department Dr Kavita Singh says, the contractual faculty is usually from among the students of Sumahendra, who cleared the NET. He/she teaches the students of miniature art, there is no regular faculty member. The 21 seats for the course often get filled. “The students are able to sell their work online, usually Punjabi NRIs are interested in miniature works of the Sikh gurus.”

With such an approach to art, the vision of Dr Goswami does not find a footing. Fine arts involve innovation, evolution of the finer senses and a pursuit of excellence in creative expression. When it is limited to course content designed to clear an exam; it loses its intent and purpose.

At the risk of sounding politically incorrect, I must say; that the course is a failure.

To begin with, for teaching subjects that involve creative expression, like painting, theatre, dance, and music; the universities and colleges should be allowed to pick faculty who is a practitioner of art and excels at it rather than imposing ridiculous conditions of Ph.D. or NET.

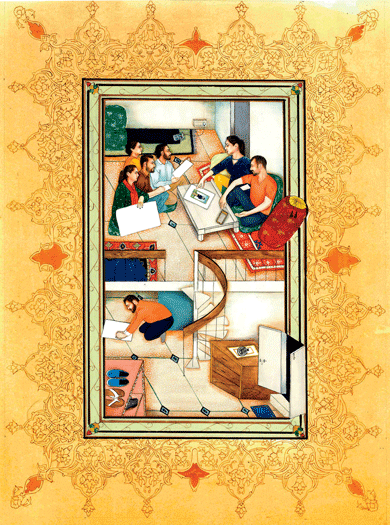

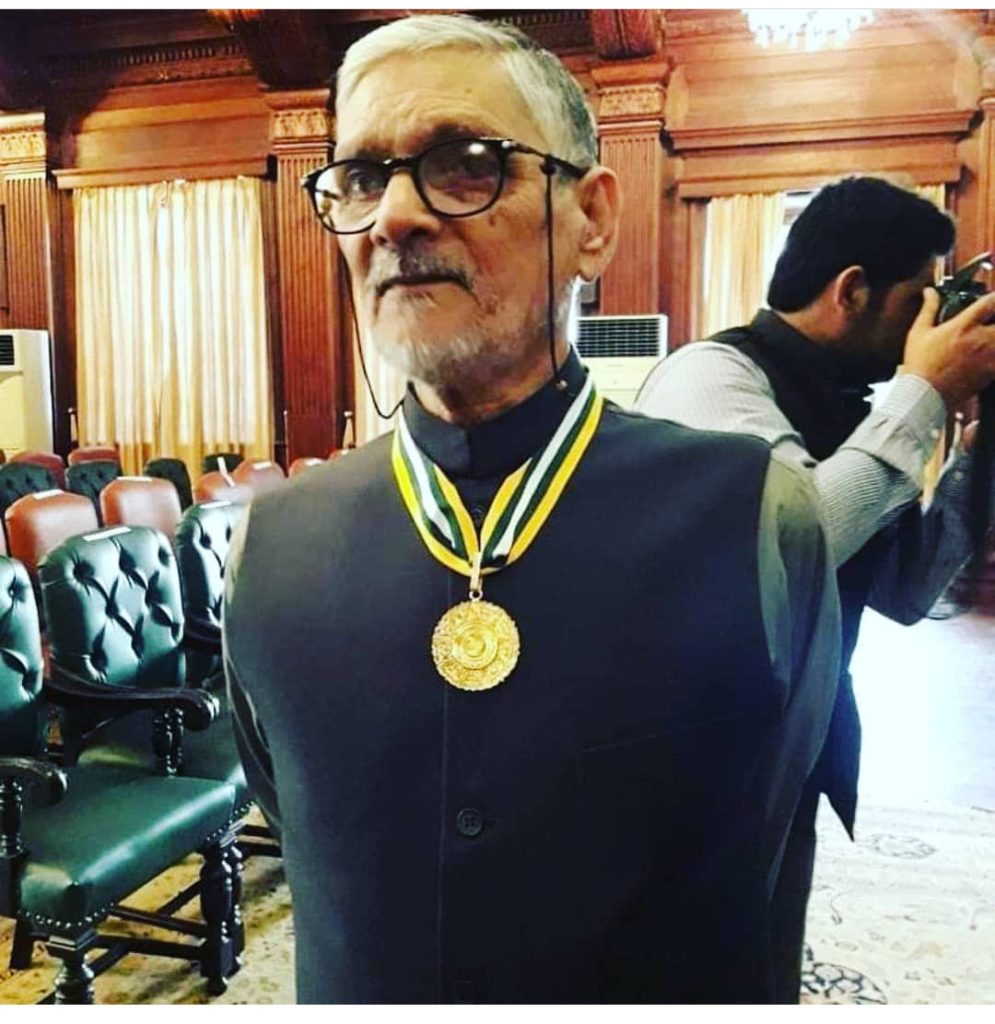

The National College of Arts, Lahore, formerly known as Mayo College, created a traditional karkhana or workshop of miniature painters in their college. The department is designed in the fashion of a traditional karkhana, with seating arrangements with back support, on the floor. The person behind the success of their miniature art course, Prof. Bashir Ahmed did not even have a master’s degree in art when he introduced the course at NCA, Lahore. Instead, what he had was—rigorous training in miniature art under the tutelage of Shuja-Ullah, a Mughal court painter’s descendant and under Haji Sharif of Patiala gharana, yes, you read it right, of Patiala gharana of miniature painting.

In Pakistan, he is known as Ustad Bashir Ahmed. Several globally renowned miniature artists are produced under his tutelage, including Shazia Sikander. When he introduced the 4-year- course in miniature art in 1982, his paper qualification was only a diploma in art from Mayo College, but his experience as a practising artist and restorer of ivory miniatures was par excellence. The then principal, Shakir Ali gave him a free hand. He did his masters in fine arts later, in 1985, from the same college.

The course designed by him demands two years of rigorous practice of control of the line—not the kind of ordinary pencil line we draw—spiral, horizontal, vertical, circular line on 1/1 ivory paper, pencil shading with chiaroscuro effect, then one year of syah kalam, followed by making of colours; kachrang, neemrang etc. and only then comes the practice of making paintings.

The Bachelor’s degree programme for miniature painting designed by him in 1982 remains to date one of the most successful programmes in producing numerous successful artists. His students who pioneered the neo-miniature movement, took this art to other countries—mostly because in their own country people do not appreciate the art and the artists get the true worth of their works abroad.

Ironically, many of his famous students started showing their works in India and Dubai, before they touched the shores of America and Europe. Under his tutelage artists like Shazia Sikander, Imran Qureshi, Ahmed Javed, Minahil Hafeez et. al. introduced contemporary elements in miniature art and took it to the next level. These artists challenged and recontextualised the technical and aesthetic framework of miniature art and pioneered an experimental approach to the genre. Now, they are celebrated globally.

Saroj Rani, who was the head of the Department of Fine Arts, at Punjabi University when Dr Goswami started the course says, “Neither he nor I was a miniature artist. He was not a painter; he did not know how to make colours, how to hold a brush, but he knew how to appreciate the painstaking fine work of a miniature artist.”

Another factor is, that Indian students of art rarely give expression to controversial issues; they shy away from making a bold statement. Our practitioners of art largely dwell in the safe- zone. The political statements made by the artists of the neo-miniature movement in Pakistan are an eye-opener. Too much burden of classicism in Indian art has become its limitation.

With good intent, Dr Goswami tried to create an avenue for the young artists of Punjab, where Sikh miniatures had evolved during the reign of Maharaja Ranjeet Singh– to explore on a small sheet of paper, a world of exquisite beauty of expression. He could not succeed in this endeavour. The pursuit of scholarship needed his solitary involvement and time; creating an artist requires more than an institution and a contract teacher.

Read Also:

Goswami’s research on Nainsukh influenced scholarship on art history

Writer | Journalist | Art Lover