Introduction

In the heart of India which has a rich cultural tradition, there exists an ancient craft—a living art more than ten thousand years old—the craft of idol-making—where legends pass through the whispering old banyan and peepul trees and the air is heavy with immortal bhakti- devotion. This elegant and mesmerising skill has been nourishing the spiritual soul of Bengal for almost three centuries, ultimately culminating in the heart of Kolkata while celebrating Durga Puja.

With the autumn breeze welcoming the festive season, Kolkata comprises of a visual spectacle in its own right. At every corner, elaborate idols and colourful pandals extend into view and nearly even the air smells of a bewitching drunkenness. Yet this tradition that one fine day wakes up Kolkata, it travels far and wide across the subcontinent calling out Bengali sculptors from Bengal as well as beyond, reaching mystical Assam with all its artisans to quench the never-satiated desire for Durga idols. These idols are the showpieces of the week-long Durga Puja festival, held each October to celebrate in cosmic proportion.

Kumartuli, the “Potter’s Locality”, where the story commences. On the other hand, resting unassumingly just half an hour north of Kolkata, this little town is not anything but difficult to miss approximately 150 potter families and nearly 550 workshops radiating in it throughout the year- artisans like marchers of a blessed fire. They do not just model idols but dreams and faith, giving the unwavering clay a form by sculpting the Mother Goddess Durga herself. These ensure the Hooghly River runs silently by, its silt part of a “Ganga family” distillate that makes an integral mix required in creating the deity.

But the craft isn’t solely bound to Kumartuli’s mystical embrace. Clay, as malleable as a lover’s whisper, is sourced from various corners of the vast subcontinent. From Ganga Mati, collected from the sacred banks of the Ganges River to Balu Mati, a particular type of clay from West Bengal, and Thakana Mati, another variety found in the lush terrains of West Bengal, as well as parts of Bengaluru—the convergence of these materials forms the foundation of divine artistry.

Kumartuli: The Birthplace of Tradition

This ancient craft is deeply rooted in Kumartuli, a town aptly named “Potter’s Locality.” Located just north of Kolkata, Kumartuli is home to approximately 150 potter families and around 550 workshops. These dedicated artisans toil tirelessly throughout the year to create the handcrafted Durga idols that grace the puja ceremonies. The Hooghly River flows nearby, providing the unique soil, locally known as “The Ganga family,” which is an essential ingredient for making an idol of Goddess Durga.

The Process: A Labor of Love

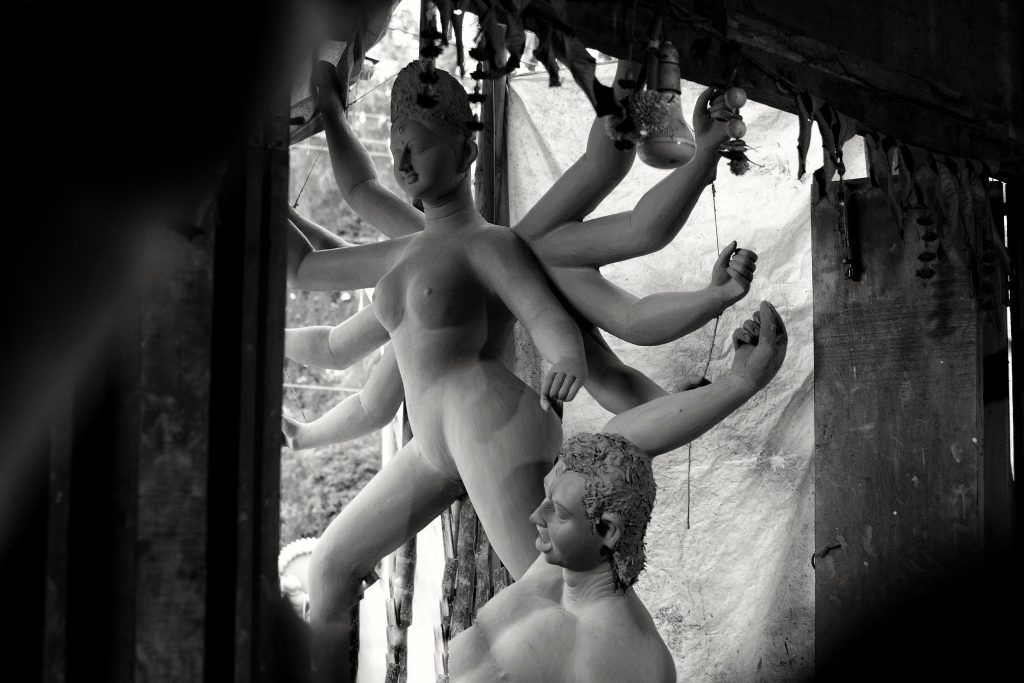

The process of crafting these magnificent idols is nothing short of a labour of love. It commences with the creation of the idol’s outline using bamboo, which is reinforced with sticks for larger creations. A grass base is formed and then covered with a mixture of mud and grass to define the final shape of the idol. The idol’s face is sculpted using pop moulds and Ganga clay, renowned for its detailed accuracy.

Water is employed to moisten the structure, and fine details are meticulously touched up. Hands and feet are manufactured separately and securely attached to achieve the desired shapes. The frame design is sometimes left to dry in the shade and then in sunlight to ensure its durability.

Once the idol is completely dry, it undergoes a painting process, which can be done by hand or with the use of a paint gun. The dress, specific to Durga’s form, is tied and secured with nails. Jute fibre is used to create the hair, with black colour for Durga and small bundles of jute fibre for the lions. The eyes considered the windows to the soul, are meticulously painted with acrylic or poster colours. The entire process is a collaborative effort, involving ten to fifteen skilled artisans.

This intricate process takes several days to complete. The work typically begins between June and August and is meticulously finished before the puja ceremonies commence. It’s important to note that every component, from the raw materials to the paint, is eco-friendly and biodegradable since the idols are ritually immersed in the river at the conclusion of the Durga Puja festival.

The Grand Finale: Adorning the Idols

Once the idols are painted, they are beautifully adorned with clothes, jewellery, and hair, often sourced from Kolkata’s bustling markets. Goddess Durga is typically dressed in a Banarasi saree, and her ornaments are made of zari, brocade, paper, thermocol, and sometimes even real gold. Durga Puja celebrations also include making idols of her children: Ganesha, Saraswati, Kartikeya, and Lakshmi, along with the central idol of Durga herself. The lion she rides and the buffalo she defeats are also carefully crafted to perfection.

Before a craftsman begins his work, a special ceremony is held in honour of Lord Ganesha, seeking his blessings as his craft is his livelihood. This blend of religious reverence and craftsmanship is deeply ingrained in the process, reflecting the cultural richness of the tradition.

The Sacred Tradition of Painting the Eyes

Another fascinating custom is the painting of the goddess’s eyes on the auspicious day of Mahalaya, just before the puja begins. To this day, the face of the idol remains covered, and the unveiling and painting of the eyes is part of a religious ceremony. It is believed that the artisan brings the idol to life when he paints its eyes, a momentous act of devotion and skill.

The Significance of “Pobitru Mati”

One of the most unique and thought-provoking rituals associated with this craft is the use of mud from the Gungan courtyard, which is mixed with smooth mud from the banks of the Hooghly River. This custom is based on the belief that when one enters a kotha (craftsman’s workshop), one leaves one’s virtues at the threshold. The soil of the courtyard patio is considered pure and is known as ‘pobitru soil.’ According to oral history, potters or priests begged courtiers for this clay. This tradition reveals a fascinating interplay between Hindu values, traditions, and social inclusion.

The Regional Nuances: Guwahati’s Artistry

Even as the heart of idol-making beats in Kumartuli, it is not a ritual bound entirely to Bengal. While Guwahati in Assam stands as one more example to this amazing craft. It starts the idol-making process in Guwahati from early March which is also known as the month of Baisakh. Artisans start work as early as January in a few cases where the orders are huge.

Speaking to local artisans in Guwahati, it becomes evident that a dedicated team of ten artisans puts in 17-20 hours of hard work every day to bring these clay sculptures to life. These skilled craftsmen wisely divide the labour, ensuring the completion of these magnificent idols within the stipulated time.

The beauty about Guwahati, using “Pobitru Mati” gets a bit of twist. The majority of artisans here are from Cooch Behar and Siliguri and hence they have their own unique “pobitru mati” with them. That said, not all the local artists in Bishnopur and Panbazar necessarily follow this particular tradition across cultures from within, to then give you a glimpse of how else they are trying to make sense of what is indigenously theirs to begin with.

The Living Story of Culture and Tradition

For Durga Puja, the art of idol-making, be it in the hinterlands of Bengal or Guwahati speaks of the variety that is an essential part of our traditions. A recognition for what these heavenly bodies look like in real life, made possible through that endless labour and commitment from expert hands. The devotion, from the time-honoured Kumartuli weavers to whom the clay is taken from the banks of Hooghly and brought to new home for goddess Durga. But what’s more that piques your curiosity are the regional quirks that colour this miasma of tradition. Each region adds so much to the fastidious process of kindling its tradition, keeping it contemporary and celebrating a culture that refuses to remain static.

The Intersection of the Sacred and Secular

Such traditions blur the line between old and new, sacred and secular but they provide us with tales that deserve to be remembered and passed on. Idol-making is not just an art form, it’s a story that lives and breathes and serves as the connective tissue of culture, history and common yarn. It crosses all borders and goes beyond time or place, touching the hearts of those who rest their eyes on its majesty.

Conclusion

India’s art of idol-making is a monument to the rich cultural fabric that connects the country’s various regions and customs. It serves as a tangible representation of artistry, spirituality, and enduring bonds across communities. This tradition represents the essence of India’s multicultural society, as each region contributes its distinct interpretations and flavours to a shared legacy, from the old lanes of Kumartuli to the busy streets of Guwahati. The art of idol-making is more than just a show of visual prowess. It honours the commitment of expert hands who give clay life and allow it to become holy. The manufactured idols are more than just simple sculptures; they are objects of adoration that represent the aspirations, hopes, and shared ideals of the societies that give them life.

Feature Image Courtesy: Karl Grenet via Flickr