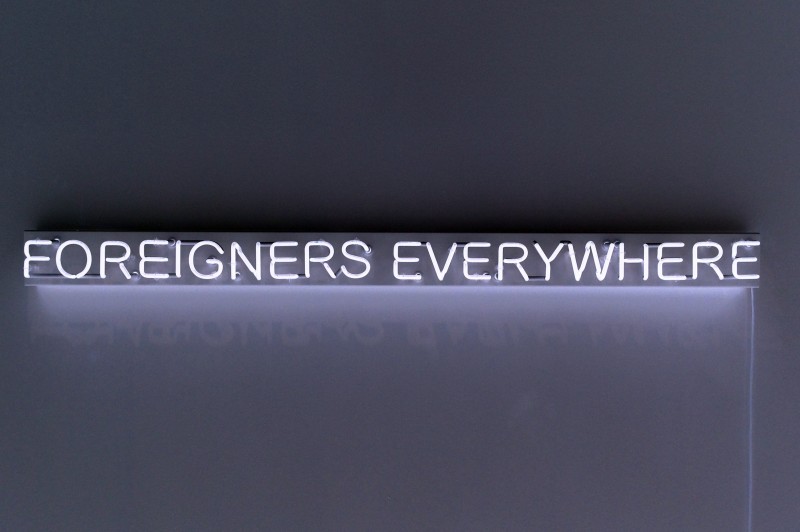

The Venice Biennale, a prestigious international art exhibition, showcases the works of nine remarkable Egyptian artists in 2024. This year’s selection highlights a diverse range of artistic styles and themes, reflecting the richness of Egyptian art history. These artists offer a compelling window into Egyptian culture and society, from social commentary to ancient traditions and portrayals of everyday life to dreamlike visions. Let’s delve into the artistic journeys of these nine masters and explore the stories behind the artworks they’ve presented at the Venice Biennale 2024.

Mariam Abdel Aleem

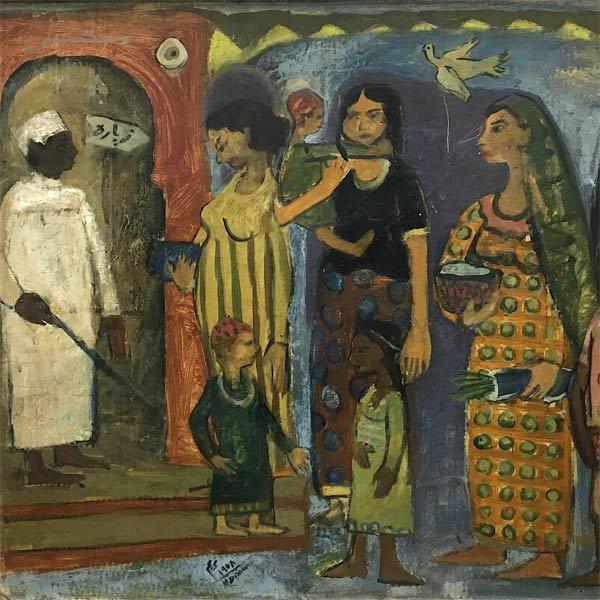

Mariam Abdel Aleem, one of Egypt’s most outstanding teachers and eminent artists, is famous for her adeptness in printmaking and her wild explorations into multiple artistic techniques and subjects. Her artworks are deeply rooted in the social themes that are deeply intertwined with the everyday life and struggles of the people of Egypt. Through her diverse and deep-rooted portrayals, Abdel-Aleem marked insightful commentary on the sociocultural discourses of her time. She was born in the early 20th century when Egypt underwent drastic changes in the socio-political and cultural fabrics.

This helped her learn and experiment with diverse possibilities of artistic expressions of life. Her works portray the scenes of people engaging in daily activities rendered with a unique blend of stylized figuration and gestural brush strokes. This method not only swallowed the essence of her subjects but also reflected her work with a dynamic, expressive beauty. One of her famous works, “Clinic” (1958), explains her subjective and stylistic characteristics. In this painting, a line of patients waiting at the entrance to a doctor’s clinic conveys the profound experience of Egypt’s healthcare system and social conditions in the mid-1950s. The subjects are the women with their children standing in a queue with bowls of food dressed up in colourful patterned fabric cloths. Above them is a flying white dove in the wall, symboling hope, peace, and joy. The frame is filled with emotional depth and intimacy. Abdel-Aleem’s works of art have been identified and celebrated in Egypt and worldwide as a great visionary, teacher, and way-shower. She inspired a generation of artists. Her work was showcased in many art Biennales worldwide, including the prestigious 1964 Art Biennale.

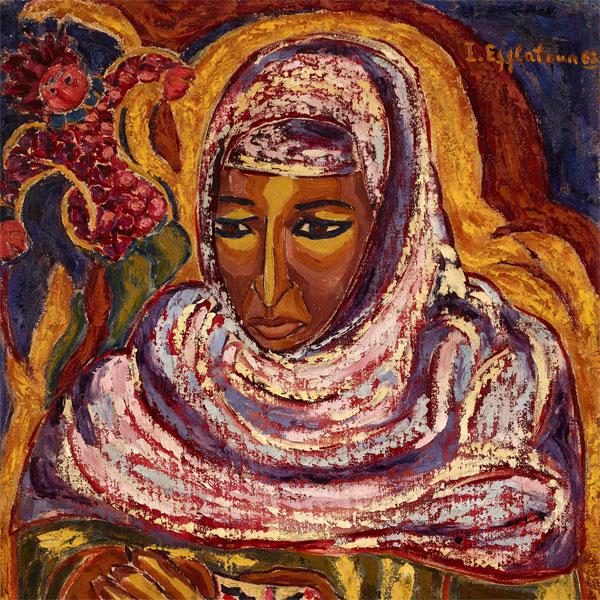

Inji Efflatoun

Inji Efflatoun was born into a Turkish-Circassian aristocratic family in Cairo (1924). Later, she renounced her socio-cultural privileges and became the loud voice of the underprivileged people in her neighbourhood, especially women. She was a great artist who used art as a weapon against injustice. She was popularly known as a feminist, Marxist, and anti-colonialist artist and activist, “Prisoner,” also known as “Ahlam al-sitt Bahanna” (1963), was painted during her four-year imprisonment. Coming from high society, Efflatoun sought to understand the lives of ordinary Egyptians and saw prison as a chance to connect with poor women. Through her portraits of fellow inmates, she highlighted the impact of poverty on women. “Ahlam al-sitt Bahanna,” meaning “The Dreams of Lady Bahanna,” depicts a prisoner named Bahanna embroidering a garment for a child she hopes to have. This scene reflects an event where women prisoners, including Efflatoun, gained the right to do manual labour after a hunger strike. Efflatoun’s works were showcased at the Biennale Arte in the Egyptian Pavilion in 1952 and 1968 and in the Central Pavilion in 2015.

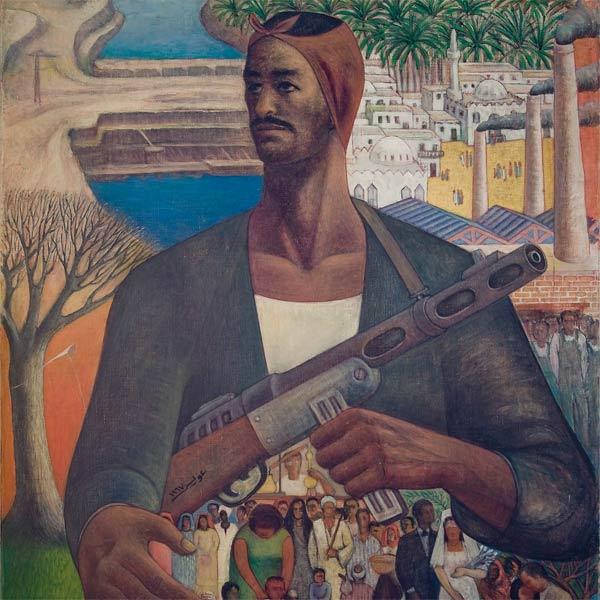

Hamed Ewais

Egyptian artist Hamed Ewais, known for his dedication to portraying the struggles of the country’s working class, graduated from Cairo’s School of Fine Arts in 1944. He furthered his education at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando in Madrid from 1967 to 1969. Ewais paints an oversized soldier looming protectively over a group of Egyptian civilians engaged in various daily activities – a wedding, a mother nursing, children riding bikes, a scientist experimenting, and a couple lovingly embracing. Painted in the crippling aftermath of the 1967 Arab– Israeli War, The Protector of Life offers an image of strength but also caution: the soldier securely holds his rifle in one hand, whereas his other tenderly shields and protects the people going about their daily lives. Beyond the cradle of the soldier’s enlarged hand, to the right, lies a deserted landscape and a barren tree, suggestive of Egypt’s loss of the Sinai Peninsula during the 1967 War. In the distance are depicted a plantation, a village, a factory, and a group of workers. This is the first time the work of Hamed Ewais is presented at Biennale Arte.

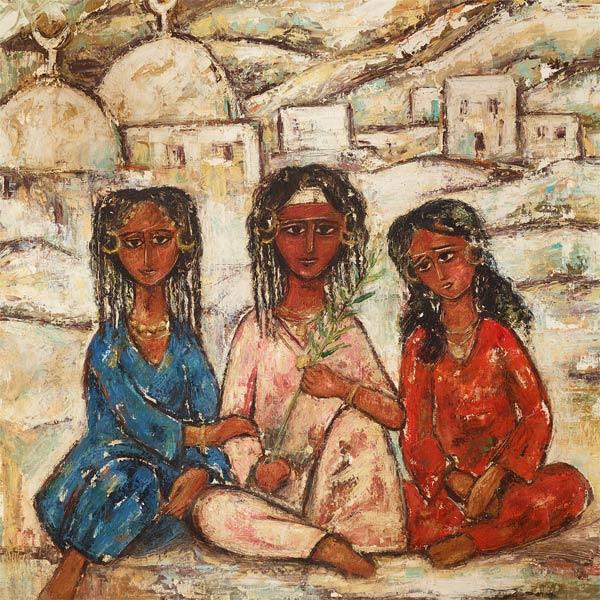

Tahia Halim

Tahia Halim was born to an aristocratic Egyptian family in Dongola, Sudan (1919). Halim’s name is closely associated with Nubia. In 1962, she was commissioned by the Egyptian Ministry of Culture to document the region of Upper Egypt that spreads to the north of Sudan. As a result of the Aswan High Dam’s construction (1960–1970), many Nubian villages disappeared under the Nile’s waters, and the populations were forced to migrate. Three Nubians feature three women seated in a hilly landscape. The central figure carries a palm leaf, a recurring motif in Halim’s Nubian paintings, particularly in scenes such as The Wedding Ceremony in Nubia (1964). The stylised faces and silhouettes of the frontal figures lend a timeless dimension to the scene. Halim presents an image of a culture with ancient and African roots. In the background, mosque domes standing alongside traditional mud-brick houses evoke the Islamisation of Nubia, originally a Christian region, reflecting a centuries-old history of its assimilation and discrimination by Egypt. Works by Halim were exhibited in the Egyptian Pavilion at Biennale Arte in 1956, 1960, and 1970.

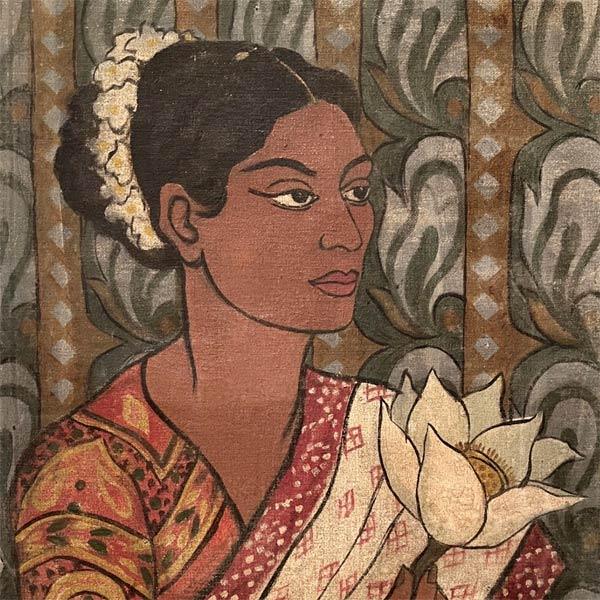

Nazek Hamdi

Egyptian artist and educator Nazek Hamdi (Cairo, Egypt, 1926-1919) was celebrated for being a pioneer of batik art in the Arab region. Her painting titled The Lotus Girl (1955) features a female protagonist in profile, dressed in a vibrant, patterned sari, wearing a flower crown, and carrying an elegant white lotus flower native to India. The patterned backdrop of this composition takes the lotus flower as a motif, repeated and juxtaposed with bold geometric forms, pointing to traditional batik patterns. Painted the year that Hamdi moved to begin her studies in India, The Lotus Girl is informed by her classical training in India, Indian subjects, and her clothing as a student there. Her use of bold black outlines, flat, even tones, and stylised, elongated forms can be credited to her specialisation in ancient Oriental arts, miniature painting, mural painting, painting on silk textiles, and the art of batik, which largely inspired her practice. This belongs to a series of works produced in India depicting Indian subjects, including mural paintings at the universities of Tagore and Rajasthan. Hamdi exhibited widely in Egypt and internationally.

Effat Naghi

Effat Naghi, born into a privileged family of landowners in Alexandria, was exposed to the arts of drawing, painting, and music from a young age. In the late 1950s, her artistic style shifted. Inspired by her fascination with Egyptian history and folklore, her work became characterized by bold colours, simplified forms, and figures. The composition and naturalistic palette of this untitled portrait bust of a woman is more classical. The vertical format, the ochre and brown shades, the model’s sophisticated hairstyle and white tunic, and the black lines accentuating her large eyes and eyebrows are reminiscent of Fayum portraits that covered the faces of upper-class mummies from Roman Egypt. However, Naghi’s use of chipboard, a material with visible particles that often served as a base for her paintings, along with the addition of bright green, blue, and pink highlights on the model’s face and hair, resulted in a modern interpretation of this ancient panel painting tradition. The background is animated by lines in black ink, tracing what seems to be symbols and writings evoking the magic words that Naghi sometimes incorporated into her paintings. Effat Naghi was one of the artists representing Egypt at Biennale Arte in 1950, 1952, and 1956.

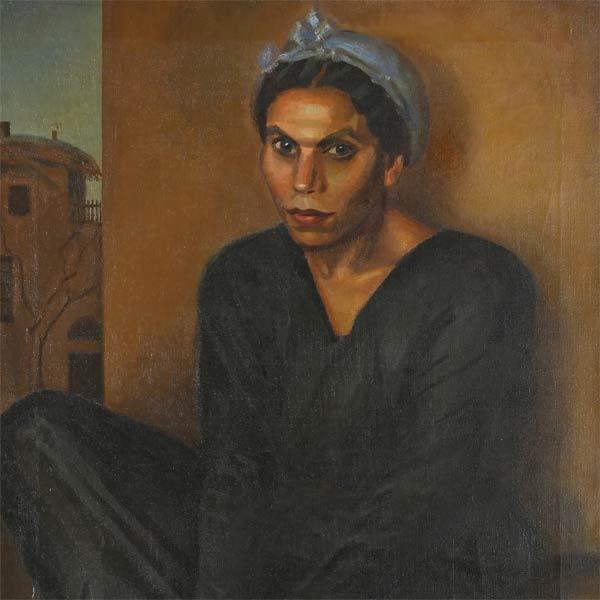

Mahmoud Saïd

In 1947, Mahmoud Saïd ditched his judge’s robe at the Alexandria Mixed Courts to fully embrace his passion for art. A defining aspect of his artistic journey became a series of captivating portraits featuring women. One such example is “Haguer” (1923). The work was exhibited for the first time in a group show for modern Egyptian artists in 1924 in Cairo. Here, Saïd depicted a woman sitting on the floor with her back resting against a wall and staring at the viewer. Contrary to the women from the Westernised local elite, the character doesn’t wear any jewellery and is attired in a simple dark dress with light blue headwear. The Alexandrian painter thus reveals that the model comes from the working class, as she is also posing humbly, her hands clasped. However, he gave this ordinary woman a sacred aspect by reflecting a golden external light on her tanned complexion. Saïd liked to celebrate the lives and customs of ordinary Egyptian folk, who personified the Egyptian identity’s essence.

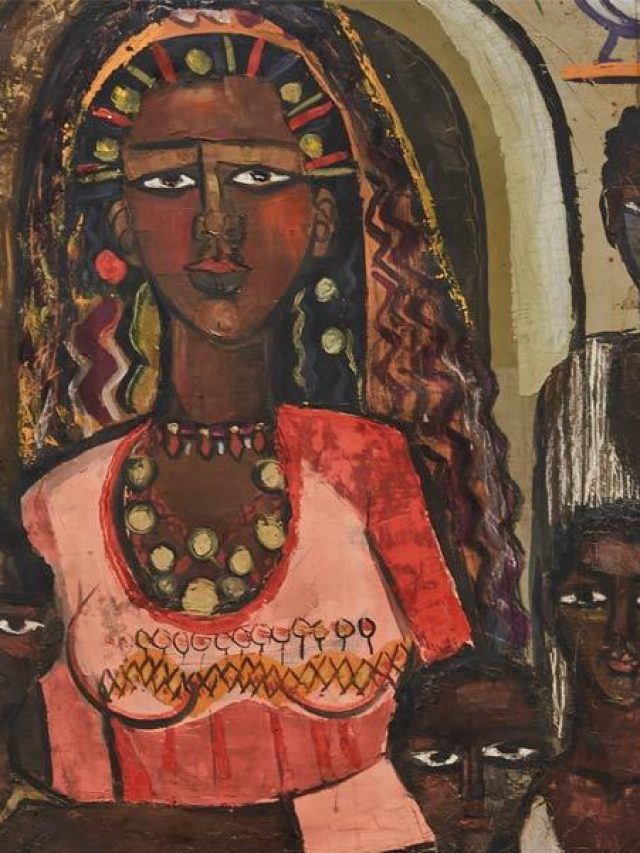

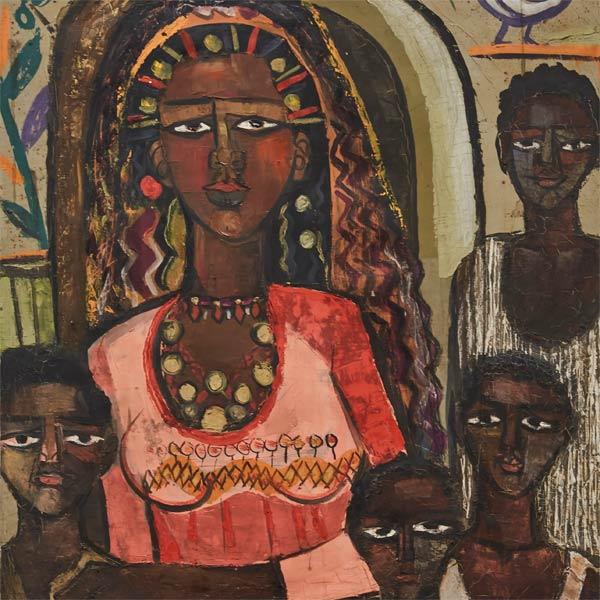

Gazbia Sirry

Gazbia Sirry, born and raised in Cairo, rose to artistic fame in the 1950s. During this period, she witnessed the 1952 Free Officers Revolution that reshaped Egypt, followed by the implementation of socialist and Pan-Arabist ideals under President Gamal Abdel Nasser. In her work Portrait of a Nubian Family (1962), referring to the Nilo-Saharan ethnic group indigenous to parts of Sudan and Egypt, Sirry paints a mother surrounded by four children. The woman wears a brightly coloured, patterned dress, while her hair and body are adorned with elaborate jewellery. The family stands in front of what appears to be an arched doorway into a mud-brick house typical in Nubian villages. The house’s outer walls are adorned with geometric, floral, and animal motifs. Including the ornamental elements in the painting reflects Sirry’s interest in heritage, mythology, and symbolism drawn from folk culture. The work was painted during the construction of the Aswan High Dam, which resulted in the flooding of large swaths of Lower Nubia and over one hundred thousand people being resettled.

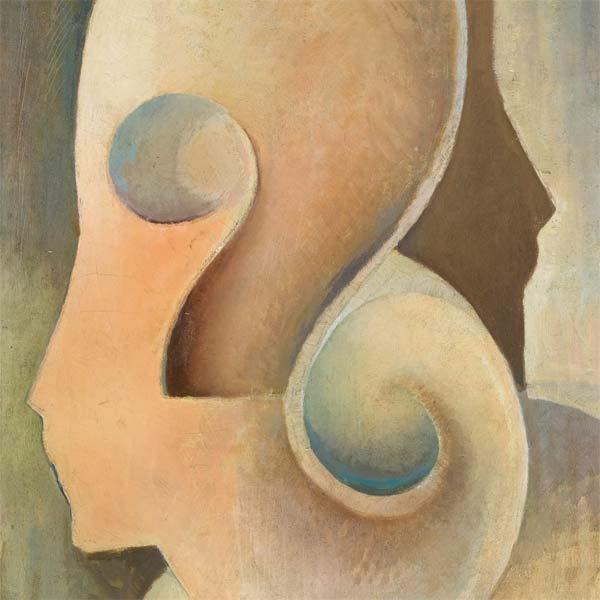

Ramsès Younan

In 1938, Ramsès Younan, a painter, writer, and critic, didn’t shy away from controversy. He signed the manifesto “Long Live Degenerate Art!” This bold move was followed in 1939 by another significant act: Younan and Georges Henein co-founded the Art et Liberté group. This collective brought together artists and intellectuals who breathed life into a unique brand of surrealism with Egyptian roots. His work Portrait (n.d.) features two superimposed silhouettes of faces rendered abstractly. The frontal face stretches into voluminous coils, reminiscent of a seashell sliced open or an enlarged inner ear section. On the other hand, the face in the back is shadow-like and flat. Separated from one another and looking in opposite directions, the faces appear estranged and alienated. Juxtaposing the two images, Younan divulges his Surrealist fascination with dreamlike compositions, the subconscious mind, and distorted, biomorphic shapes. Younan’s work frequently featured tortured or dismembered bodies as a commentary against repression and in support of women’s rights.

Jain Syriac Babu is a Kerala-born, Italy-based theatre artist and art enthusiast.