Who was Ellsworth Kelly?

Ellsworth Kelly, an iconic figure in American minimalist art, was born in 1923 in Newburgh, New York. As the second eldest of three brothers, Kelly spent much of his childhood in northern New Jersey, immersed in solitude and the natural world. Observing birds and insects, he cultivated a sensitivity to form, colour, and movement, elements that would later define his unique approach to abstract art.

Early Life and Education

Kelly’s formal journey into art began at the Pratt Institute in 1941, where he studied technical art and design. His education was soon interrupted by World War II, during which he served in the U.S. military. Stationed in France, England, and Germany, Ellsworth Kelly had a brief but transformative stay in Paris. Exposure to camouflage, shadows, and military aesthetics deeply influenced his artistic vision and planted the seeds for his eventual minimalist style.

Courtesy – e-flux

After returning to the United States in 1945, Kelly enrolled at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts School. For two years, he explored traditional, figurative art forms. However, it was his return to Paris in 1948, supported by the G.I. Bill, that marked a decisive shift in his artistic identity. Enrolling at the École des Beaux-Arts, he began distancing himself from both Abstract Expressionism and the prevailing American art movements.

Paris: The Birthplace of Abstraction

Unlike many contemporaries, Ellsworth Kelly didn’t pursue abstraction as a rebellion. Instead, he approached it as a distillation of visual experience. Influenced by Romanesque and Byzantine art, Picasso, and Surrealist automatic drawing, he developed a minimalist visual language rooted in chance, perception, and simplicity.

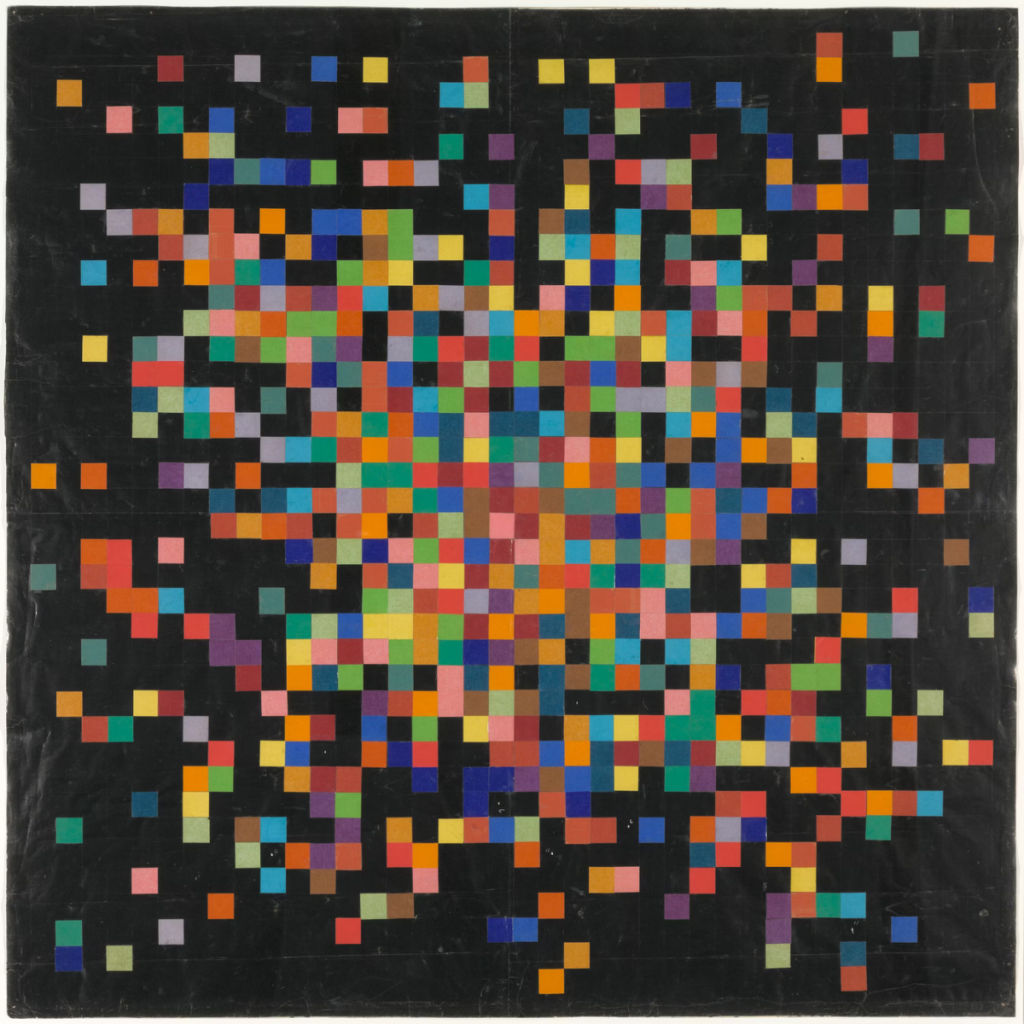

Oil on canvas, 64 panels.

Courtesy – Museum of Modern Art

A pivotal moment occurred during a visit to the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris, where Kelly found more inspiration in the structure of the windows than in the art on display. This observation led him to reinterpret architectural forms as art. From then on, he committed to eliminating expressive marks, lines, and edges from his paintings, focusing instead on form, structure, and colour.

Minimalism in the American Context

When Ellsworth Kelly returned to the U.S. in 1954, he became part of a burgeoning community of artists who opposed the intense psychological expression of the New York School. Unlike Abstract Expressionists, who prioritised emotion and spontaneity, Kelly and his peers, including Robert Indiana, Agnes Martin, and James Rosenquist, pioneered a style based on colour fields, observational forms, and reductive composition.

Oil and Ripolin on Masonite.

Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Kelly’s distinctive style provided a roadmap for Minimalist sculptors like Donald Judd, Carl Andre, and Richard Serra. His influence even extended to Donald Sultan, whose simplified depictions of everyday objects echoed Kelly’s restrained visual logic. Beyond the fine art world, Kelly’s aesthetics also left a mark on graphic design, particularly in the post-WWII era.

Pioneering a New Visual Language

Ellsworth Kelly’s contribution to 20th-century American art lies in his redefinition of abstraction. He eschewed generalisations in favour of concrete visual details, producing single-colour panels, multi-panel compositions, and works that incorporated randomness and repetition. These techniques revolutionised modern art and signalled a departure from the emotional and narrative-driven practices of previous decades.

Public Commissions and Later Work

In addition to gallery exhibitions, Ellsworth Kelly made a significant impact through public art commissions. Notable works include a sculpture gifted to Barcelona in 1978 and an installation for the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., completed in 1993. His sculptures, like his paintings, reflected his commitment to clarity, geometry, and spatial harmony.

Courtesy – Ellsworth Kelly Foundation

Despite facing health challenges later in life, including the use of an oxygen tank due to what he believed were the effects of turpentine, Kelly remained active in the studio. He continued to explore new materials and formats while preserving the unmistakable essence of his vision.

Legacy of a Minimalist Master

Ellsworth Kelly’s career spanned over 70 years, during which he developed a cohesive yet expansive body of work that transcended genre boundaries. His paintings, sculptures, drawings, prints, and photographs all shared a common DNA, rooted in observation, abstraction, and elegance. President Barack Obama recognised his artistic contributions with the National Medal of Arts in 2013, cementing Kelly’s status as a monumental figure in modern American art.

Oil on Wood.

Courtesy – The Art Institute of Chicago

In retrospect, Ellsworth Kelly was not just a minimalist; he was a visionary who reimagined how we see, interpret, and reproduce the world around us. His legacy continues to inform and inspire artists, designers, and thinkers who strive for clarity, innovation, and beauty in simplicity.

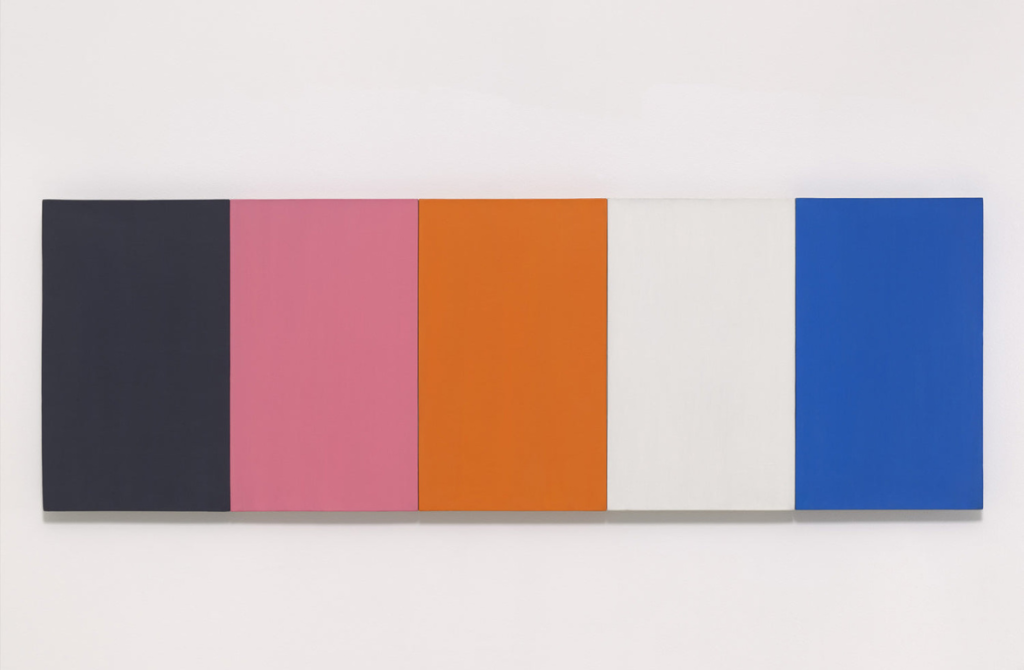

Image Courtesy – Ellsworth Kelly. Painting for a White Wall, 1952. Oil on canvas, five joined panels. Courtesy – Ron Amstutz & Glenstone Museum, Potomac, Maryland

Contributor