Abhishek Kumar

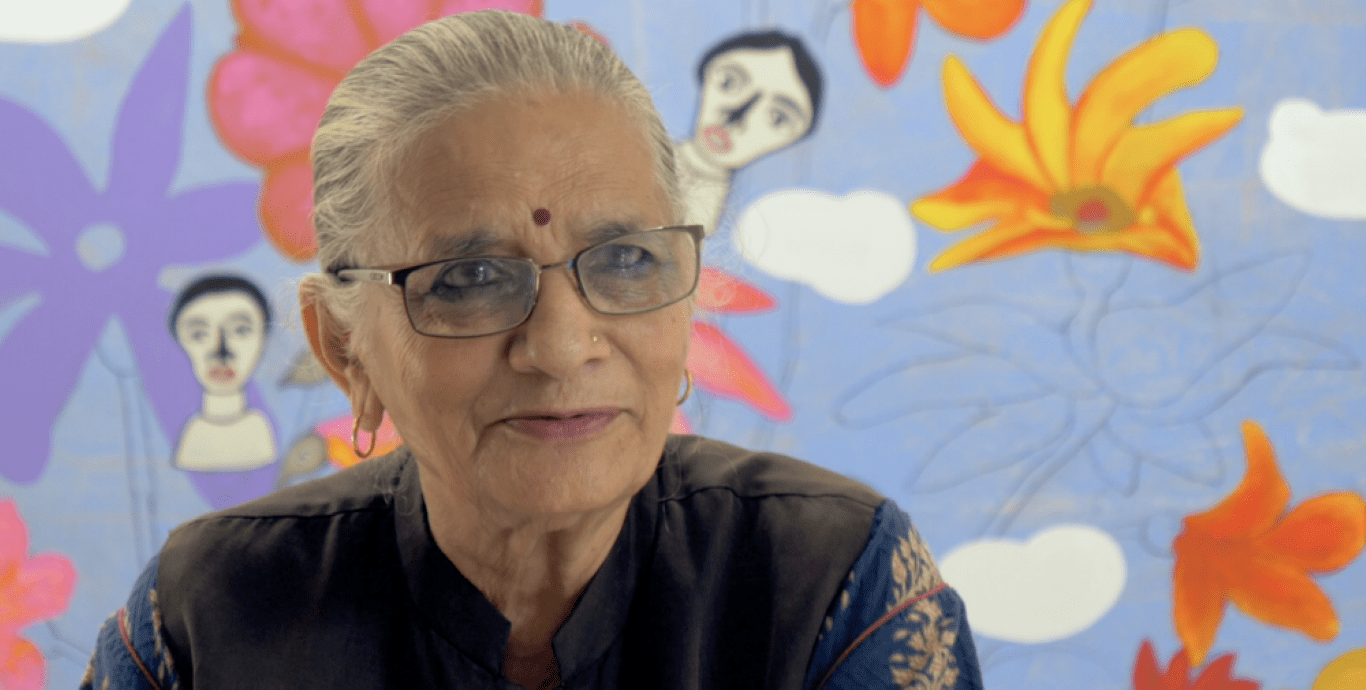

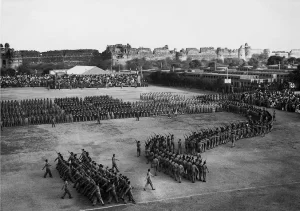

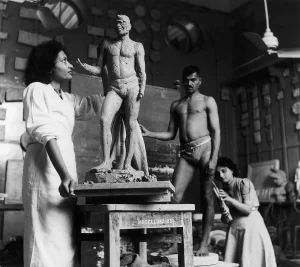

Homai Vyarawalla was a pioneering Indian photographer who captured some of the most iconic images of the country’s history. Her work spanned from the 1930s to the 1970s and documented some of the most important events in India’s independence, including the coronation of King George VI, the death of Mahatma Gandhi, and the first elections of the nation. She was the first female press photographer in India and her work is an important part of the nation’s photographic history. She went on to document key political, social, and cultural events in India, including the funeral of Mahatma Gandhi, the first visit of Jawaharlal Nehru to newly independent Pakistan, and the return of Lord Mountbatten to India.

Homai Vyarawalla was born in 1913 in Navsari, Gujarat in India. She was raised in an affluent Parsi family that encouraged her to pursue her interests in photography. At the age of 18, she married Maneckshaw Vyarawalla, a businessman, and the couple moved to Bombay. In 1936, Homai enrolled in a photography course and began working as a professional photographer. She joined the British Information Services, where she photographed important events such as the coronation of King George VI and the first elections of independent India.

She was the first female photojournalist in India and one of the few women photographers in the world at the time. Throughout her long career, she captured some of India’s most important moments and her work was published in magazines and newspapers across the globe. Her photographs of Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, and other prominent figures of the independence movement are among her most iconic images. Her photographs are now archived at the Alkazi Foundation of Photography in New Delhi.

“Somehow it never occurred to me that I was doing something unusual or that I was the only woman in a male-dominated profession at that time. I think I was casual in my dressing and unobtrusive in my demeanour, so this may have made people around me feel at ease. I was always given due credit for my work and was respected just as any other competent person in the field. At school, I was the only girl in my matriculation class. So I was used to being in the company of boys” said Homai Vyarawalla while speaking to The Hindu.

Homai was an early advocate for women’s rights. She was the first woman to join the All India Press Photographers Association and she was awarded the Padma Vibhushan, India’s second-highest civilian honour, in 2011. Her work has been exhibited in galleries and museums around the world, and her photos have been featured in numerous books and documentaries.

Homai Vyarawalla’s work stands as a testament to the power of photography and its ability to capture moments in history. Her photos are an important part of India’s photographic history and her legacy lives on through her work. Her influence is a reminder of the importance of women in photography and their contributions to the field. Homai Vyarawalla remains an inspiration to photographers around the world.

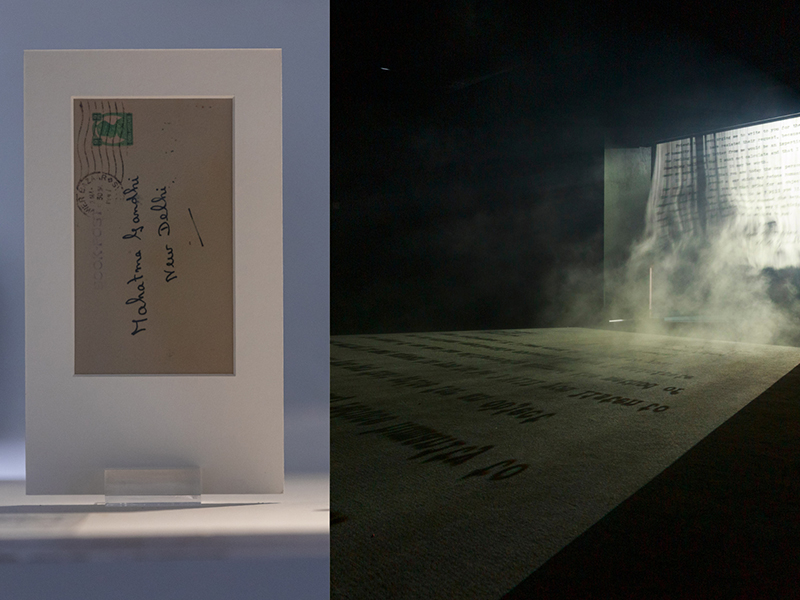

At the fifth Kochi Muzeris Biennale Jitish Kallat is curating a show “Tampled Hierarchy II” which includes photographs of Homai Vyarawalla. The show commemorates the 75th anniversary of Lord Mountbatten’s meeting with Mahatma Gandhi to discuss India’s impending partition, which Gandhi strongly opposed. Consequently, a vow of quiet on Mondays was made. The sole remaining documentation of this exchange is communication exchanges written on the backs of old envelopes. Kallat explores these archives in-depth, fusing contemporary art with the distinctions between voice and silence.