Megha Joshi ’s ongoing solo at gallery Studio Art in Okhla, New Delhi, is a sublime reflection on India’s syncretic traditions without any of the weight of religiosity

URMI CHANDA

A lot has changed in the political landscape of India in the last eight years, and the rising rhetoric of religious hatred and sectarianism is no secret. It is easy to give in to despair and cynicism, believing that India’s pluralistic fabric has been irrevocably damaged. But ask any historian, and they’ll tell you how eight years is nothing in the face of thousands of years of legacy. It is only as easy to destroy India’s diversity and plurality as it is to blow out the sun. Regardless of what the saffron-tinted media and their overlords project, India’s syncretic traditions are well alive and kicking. They live through her fairs and festivals, through her many tales of saints and mystics, through her foods and crafts, and in the hearts of her common citizens. They also live through her artists, who serve to remind us that India is such a tight and seamless weave of traditions that it’s impossible to separate its strands.

Inward bound

One such artist is Megha Joshi , whose ongoing show ‘Rite of Passage’ is a testament to India’s diverse faith traditions, with a special focus on Hinduism and Islam. A sculptor by training, Joshi has been experimenting with materials and techniques of all kinds, since she delved into full-time art practice since 2008. Before that, she used her skills as a set designer and art director in the entertainment industry. Currently based in Gurgaon, she learned and honed her craft at the Faculty of Fine Arts, Maharaja Sayajirao University (MSU), Baroda. Joshi has participated in many national and international group shows and residencies, including the India Art Summit 2009 and 2011, and in many editions of the India Art Fair from 2012 and is also going to be a part of India Art Fair 2023.

Her current show, ‘Rite of Passage’ is being exhibited at Studio Art in Okhla, New Delhi, from December 1, 2022 to February 12, 2023.

With installations and sculptures of all shapes, sizes, and materials, Joshi’s technical oeuvre is vast; however, it is the themes of religion, ritual and gender that course strongly through it. A number of her striking earlier works, such as ‘The Wound’ and the ‘Sensor/Censor’ series, have tackled themes like women’s bodies, menstruation, and sexuality. Having grown up in a family steeped in the socialist tradition, Joshi has been unapologetically vocal about her views and expressions – something that is neither common or encouraged in the art world. In the capital’s art circuit, Joshi has rightly earned the reputation of being fiercely feminist.

However, with ‘A Rite of Passage’, Joshi has started to move inwards. “My friends don’t recognise this quiet Megha,” she told me over a lunch we shared in Delhi last month. “I think I’ve started wanting to change myself instead of changing the world.” The name of her newest show may well be a reference to her personal transformation.

A rose by any other name…

Joshi may not be as outspoken an artist as she was earlier, but the force of her work remains undiminished. Like many of her former works, not just the theme of religion but materials of ritual present themselves in a way that are quintessentially Joshi. In fact, ritual materials dominate this show, since it is meant to be a reflection on the ritualistic aspect of faith. However, Joshi strips the ritual materials of religious context, and uses them in ways that forces viewers to question faith, form, and everything in between.

Some of the motifs and materials that the artist has used in her works include Islamic jali (screen) patterns, rudraksha beads, red and yellow mauli dhagas (sacred thread/ yarn used in Hindu worship rituals), cotton wicks, henna (a staining natural dye), diyas (earthen lamps), and incense sticks. Many of these materials occur in both, Hindu and Muslim contexts, and when Joshi uses them purposefully together, it blurs the boundaries of religion. One must step into syncretic waters, leaving the familiar shores of one’s fixed religious identity.

For example, in the diya wall installation titled ‘Illumination’ , she has hand-painted hundreds of earthen lamps – typically associated with the Hindu festival of Diwali – with Islamic jali and geometrical patterns, creating intentional intersections of Hindu and Muslim motifs and materials. Similarly, in her work titled ‘Syncretic Ritual’, she has dyed and glued thousands of cotton wicks – again, associated with Hindu pujas – to a plywood sheet, forming a large, unmistakably Islamic motif.

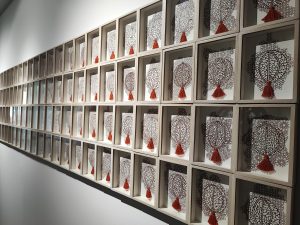

In ‘108’, a series of small drawings, the artist juxtaposes the rudraksha motif with Islamic patterns in various permutations and combinations. I could not help but note that the number 108 is sacred to Hindus, and that the artist had used rice grains – often used as akshata or sacred offerings signifying abundance in Hindu rituals – to write micro titles on each of these free-hand drawings. “The words on each of these rice grains is really what my mood predominantly was on the day I made the drawing,” Joshi told me. As I inspected the drawings closely, I noticed that one of the rice grains had the word ‘horny’ on it. After the initial shock had settled, I laughed at my own prudery and thought how the artist had managed to do exactly what she set out to do: change context and elicit a reaction, and possibly, reflection.

Another wonderful example of context removal is the largest untitled installation in the exhibition. Lakhs of agarbattis are tied and glued together, twisted and propped up in weird and wonderful shapes, inviting awe and contemplation from a visitor. However, Joshi has used fragrance-free versions, which to use her term, are ‘nonsense sticks’ without the incense. It makes one curious about the worth of a sacred ritual object outside of the ritual space and sans the key attribute. It makes one question the way we get attached to objects and symbols, and the way we rise (often exaggeratedly) to defend them. Would a rose by any other name really smell as sweet?

Much food for thought

Other works of note at the exhibition include ‘Dwar/Darwaza’, which is an intended replication of Islamic architectural patterns at the Humayun’s tomb in Delhi, around which the artist grew up. The geometrical shapes are created with cotton wicks and the interstices are filled with painstakingly drawn intricate patterns. These patterns resemble mehendi or henna designs adorned by South Asian women, both Hindu and Muslim, on auspicious occasions and were made by the artist by hand, using cones just like the ones used by mehendi artists. The only difference was that these cones had acrylic paint in them instead of mehendi paste.

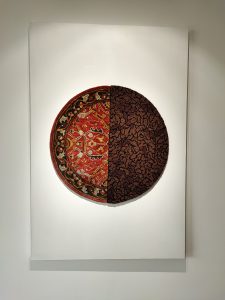

In the works, ‘Casual Synchronicity’ and ‘Agnostic’, the artist juxtaposes more such Hindu and Islamic designs. In these pieces, she has used knotted yarn to create the patterns, and each of the lakhs of knots used are made and glued by her one painful square centimetre after another. This labour-intensive process is meditative, and achieves for the artist the same effect as it does for a devotee performing a ritual inside a temple or a mosque, in private worship or public pilgrimage.

Joshi’s idea of faith transcends manmade religious spaces and flows into natural realms as well. This is reflected through the work ‘Mapping Faith’, where hundreds of rudraksha beads and bits of sacred thread have been used to create biomorphic forms, and another untitled series of four coral-like stones adorned with similar elements. It is a tribute and a reminiscence of her experience of snorkelling, which she describes as a ‘deeply divine’ experience. It presents these questions to a viewer: can everyday articles of faith infuse nature with sacredness? Are they even needed? Isn’t nature divine as it is? If so, what does our abuse of nature say about our faith?

Megha Joshi’s ‘Rite of Passage’ offers one the opportunity of stepping away from the cacophony of relentless religion-laced propaganda, and spend some moments of quiet contemplation on the nature of one’s private beliefs and expression of public religion. It may well be a portal from which a viewer emerges with altered ideas of the self and the other, the many ways in which faith can manifest, and how beautifully syncretic it all can be. It is definitely a journey worth making.