Manjeera

March 15, ON THIS DAY

Naturally many may naively and rambunctiously ask why would a black artist concern himself with the wider questions of art and humanity?

…my answer is art and ideas belong to no particular people exclusively. If they did this art has failed to reach the transcendent state that artists have been trying to attain for at least forty thousand years.

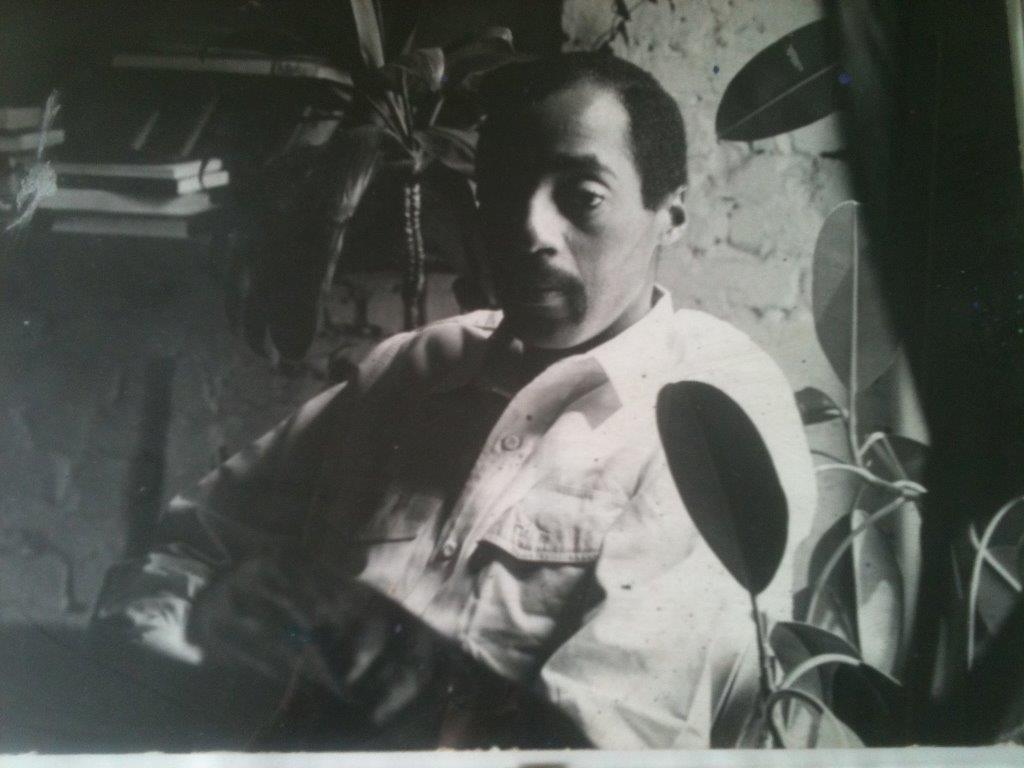

– Emilio Cruz

Emilio Cruz did not believe that art had no purpose apart from being purely decorative; serving just to please the eye and heart. He was a firm believer of the idea that art had a mission, and for an artist to produce art that had any amount of significance, he was certain that the artist must have commitment to humanity and firm morals that they would not betray. Art, in the right circumstances, he believed was this ultimate form of expression that could impact perception eternally, achieving a transcendental status, breaking free of all logical barriers.

This visual artist and playwright was led by his own ideological and philosophical convictions and more importantly, his desire to help people throughout his life– a quality that is reflected in his artwork. His art was unique and complex; ranging from vivid and colorful works where the human form was celebrated to monotonous paintings that fused human and animal figures with archeological imagery. His work was intent on exploring the root of what it is to be human, and much of it can be labelled as an artistic inquiry into the philosophical.

Emilio Cruz was born in the Bronx, New York City just before the second World War in 1938. Most of his childhood was spent shuttling between the Bronx and Harlem, where he experienced the essence of the city. His father played a significant role in inspiring Cruz down the artistic path as he himself was a trained artist. Cruz learned his first artistic lessons through his father and joined the Art Students League after high school. To make ends meet, he used to work as a commercial artist and could only take night classes at the League.

Courtesy: Patricia Cruz

In the 50s, Cruz spent time in the art colony of Provincetown, Massachusetts. He met other contemporary New York avant-garde artists who were exploring figurative art and abstract expression, trying to make the two distinct art forms reach a co-operative bridge through their artwork. Cruz was immediately taken by this concept and joined in, with elements of his art fusing the looseness and fluidity of abstract expressionism with the trace of a structural integrity brought in by the figurative elements. He received a lot of guidance during this time, and he studied under Chinese painter and printer maker Seong Moy, who was known for his abstract and vibrant prints. He made many useful connections and became good friends with figurative painter Bob Thompson, abstract expressionist Franz Kline, and poet Charles Olsen.

As racial tensions were reaching their breaking point in America and violence against African-Americans was peaking, Emilio and his partner Patricia Cruz, moved to St. Louis to work with the Black Artists Group. Emilio was only thirty at this point, but he had already developed a strong reputation as an artist and had own several awards such as John Hay Whitney Fellowship. He was a little reluctant to switch cities, but Cruz was strongly affected by the deaths of Martin Luther King Jr and Malcom X and decided to do his part. The artist describes this as his “chosen way” and “personal struggle”; this was important to him. He ended up serving as the director for the visual arts program. Patricia was also deeply involved with the struggle; she was a civil rights organizer and had worked with the War on Poverty project in Queens. Both of them were an active part of the resistance and participated in civil rights protests and strikes all over the city.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum

A closer look at Emilio’s art from this period reveals its intricacies– the subtle way the artist combined expressionism, the abstract and the figurative is genius. In his 1962 piece The Dance, we can see the fluid nature of his painter’s brush, with paint dripping from the canvas, leaving streaks across various parts of the painting. There is only a vague sense of what this painting is supposed to represent, and without the linguistic cue that is the title of the painting, it might be hard to decipher exactly what was happening. There are vaguely human figures, identifiable due to their peace coloration and vague anatomical structures; these figures are in motion but the abstractness of the composition hinders actual perception. The viewer can only put together that this is a dance after the semantics of the title are realized. Though Cruz used the peach color to indicate human forms, he also experimented, trying to lose the peachy whitish color. This is visible in Figurative Composition #7 (1965), where the figures are instead drawn with pink, with only slight traces of peach present.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum

In the 70s. Cruz ended up taking a teaching position at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. He started getting into philosophy around this time and started writing plays. His works now started exploring the origins of humanity, the essence of what is it to be human. To explore this, Cruz studied paleolithic art and scriptures of various religions, especially Hinduism. He wanted to investigate the core of all human experience and create art whose meaning is so easily perceptible that it becomes transcendental. One of his 1968 pieces, Thanksgiving and Other Holidays, reflects the artist’s transforming inclinations. There is strong juxtaposition here of different visual elements that grew out of the artist’s study of various religious and cosmologies.

Courtesy: The Studio Museum in Harlem

Courtesy: Alitash Gallery

Cruz continued to explore this particular stream of thought in his later period, and the core of his later work is best represented in the 2004 exhibition titled I Am Food I Eat The Eater Of Food. This was the last exhibition of the artist while hewas still living as he passed away due to pancreatic cancer just a few days after the exhibition ended. The title is a reference to a phrase from the Upanishads and the larger purpose of the exhibition is to exude upon the purpose of life. Cruz’s personal ideology about art was greatly influenced by Hindu philosophies and he believed that life is a constant contradiction where the opposite is also always true.

References:

https://web.archive.org/web/20120207104112/http://www.alitashkgallery.com/emiliocruz/