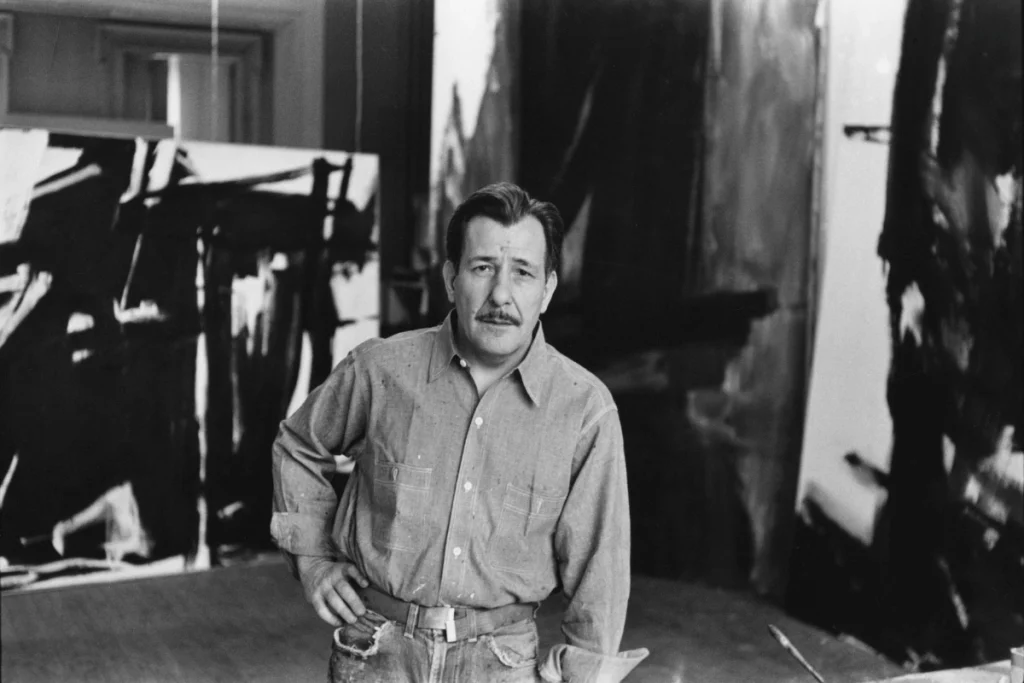

Franz Kline: The Abstract Expressionist Who Redefined Modern American Art

Franz Kline, a towering figure in Abstract Expressionism, was born in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, a coal-mining town that offered little encouragement for artistic exploration. Despite this unremarkable beginning, Kline emerged as a leading American painter whose bold brushwork and black-and-white abstractions would become emblematic of post-war American art.

Early Life of Franz Kline: Tragedy and Transformation

Franz Kline’s childhood was fraught with emotional upheaval. His father passed away when Kline was still a young boy, and his mother subsequently left him in an orphanage before remarrying. This unstable upbringing deeply influenced Kline’s psychological landscape, laying the foundation for the emotional intensity that would characterize his later work.

Courtesy – From The Studio via SubStack

Later in life, personal challenges persisted. Kline’s wife struggled with mental illness, requiring repeated hospitalizations. These experiences of loss, abandonment, and emotional turmoil uniquely prepared Kline to resonate with the existential themes explored in the Abstract Expressionist movement, which emphasized the subconscious mind and mystical enlightenment in the aftermath of World War II.

Academic Journey and Artistic Evolution

Kline began his formal studies at Boston University from 1931 to 1935 before attending the Heatherley School of Fine Art in London from 1937 to 1938. He relocated to New York City in 1938, where he first worked in a style blending Cubism with Social Realism, reflecting real-world figures and scenes.

Courtesy – Art of Darkness

A pivotal moment came in 1949, when Kline projected his small sketches using a Bell-Opticon projector, revealing their latent potential as large-scale abstract paintings. This discovery marked the beginning of Kline’s foray into monochromatic abstraction, a shift that would define his legacy.

Abstract Expressionism: Black and White, Form and Gesture

Though trained in traditional figurative techniques, Kline evolved into a master of gestural abstraction. He drew inspiration from peers in the New York School, including Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, Robert Motherwell, and Hans Hofmann. These connections encouraged him to abandon figurative constraints and embrace action painting, a dynamic and expressive approach that emphasized physical motion and raw energy.

Courtesy – National Gallery of Art

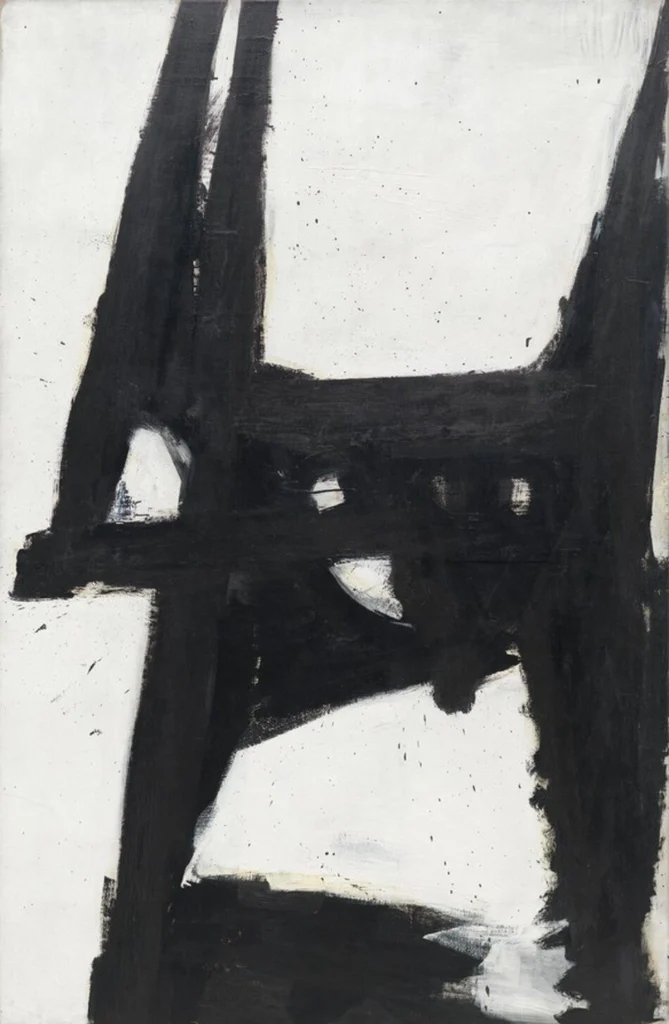

His iconic works like Nijinsky (Petrushka) and Mahoning (1956) showcase thick black brushstrokes slashing across white canvases. These paintings, though seemingly spontaneous, were the result of careful planning, often sketched out on old telephone books before being transferred to canvas.

The Symbolism Debate: Subconscious or Formalist?

While critics often speculated about the influence of Japanese calligraphy in his work, Kline denied these interpretations, emphasizing the non-representational and formalist nature of his paintings. He believed in the viewer’s unfiltered experience of the art, free from imposed meanings or symbols. As Kline stated, the value of his work lay in the painting experience itself.

Courtesy – ArtsDot

Critic Clement Greenberg supported this interpretation, viewing Kline’s work as a celebration of pure abstract form over psychological content. This distinguished Kline from contemporaries like Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman, whose work often carried spiritual overtones.

Transition to Color and Later Works

Although Kline is best known for his black-and-white compositions, he began incorporating color in the mid-1950s. Works like Black Reflections reveal a deliberate expansion of his visual vocabulary, hinting at new directions while retaining his commitment to gestural precision.

Courtesy – WNEP

In his final years, Kline moved toward more structured compositions, marked by bold simplicity and a refined formal elegance. These later works reflect a mature artist in control of his medium, blending the emotional resonance of Abstract Expressionism with the visual clarity associated with Minimalism.

Franz Kline’s Legacy in Modern Art

Franz Kline remains a central figure in the history of modern American art and 20th-century painting. His work bridges the gap between Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism, emphasizing form, gesture, and the materiality of paint. While others in his movement explored the spiritual or the subconscious, Kline rooted his work in the physical act of painting itself.

Courtesy – Learn – NCART Museum

By rejecting mysticism and symbolic interpretation, Kline offered an alternative approach to abstraction, one that focused on visual rhythm, compositional balance, and the power of black-and-white contrasts. Today, his paintings are held in major collections around the world and continue to inspire artists and scholars alike.

Image – Franz Kline. Mahoning (1956) Courtesy – Whitney Museum of American Art

Contributor