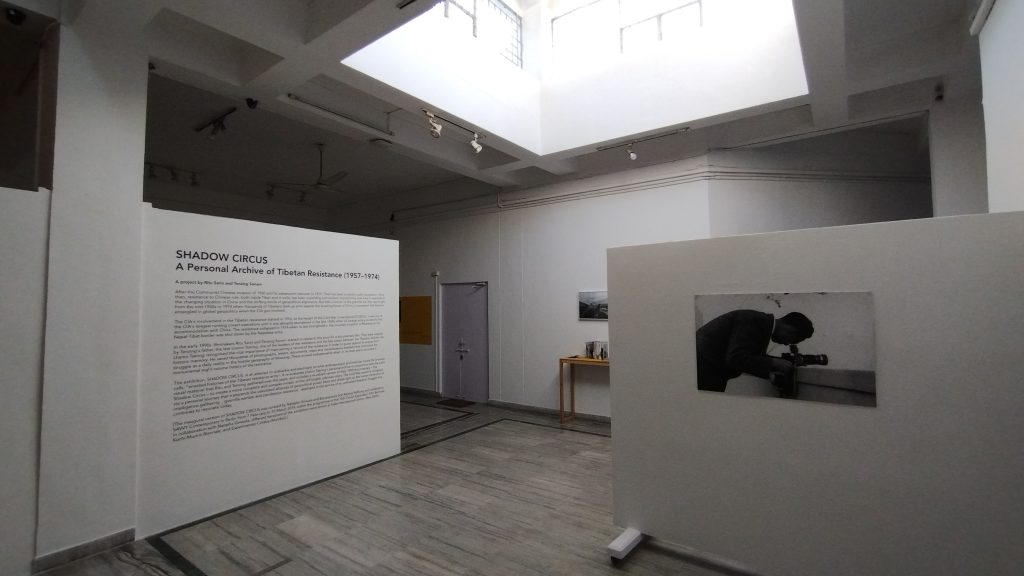

Tenzing Sonam and Ritu Sarin’s powerful exhibition Shadow Circus can be described as a memorialising project that throws much-needed light on a lesser-known episode from the history of Tibet, a nation that has witnessed systemic colonisation over the past seven decades. Through the use of archival material, it documents the intrepid resistance put up by the Tibetans following Communist China’s invasion in 1950, which manifested in a full-fledged guerilla war that lasted till 1974. The inaugural version of Shadow Circus was exhibited at SAVVY Contemporary in Berlin in 2019, as part of the 14th Forum Expanded, 69th Berlinale. Curated by Natasha Ginwala and Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, subsequent iterations of the exhibition showed at India International Centre in New Delhi, the Kochi-Muziris Biennale and Experimenter-Colaba in Mumbai. On 15th February, Shadow Circus was inaugurated at the newly renovated gallery space at the School of Arts and Aesthetics, JNU in New Delhi.

Image courtesy: Author

Tenzing’s father, Lhamo Tsering, was an important leader in this resistance movement, which, most interestingly, saw the active involvement of the CIA. Committed to thwarting the rising influence of Communist China in South Asia, it was in the US’ interest to lend support to the Tibetan cause. Apart from supplying weapons and funding, they would even recruit Tibetan men, train them in tactics of spy craft and guerilla warfare and air-drop them in Tibet. These trained ‘spies’ would then collect intelligence regarding the Chinese army, galvanise rebel groups and mount attacks on the aggressors. Tsering was a key point of contact between the Tibetans and the Americans. Over the years, he had painstakingly stored several documents and photographs related to the resistance movement; most of the materials on display are drawn from his personal archive.

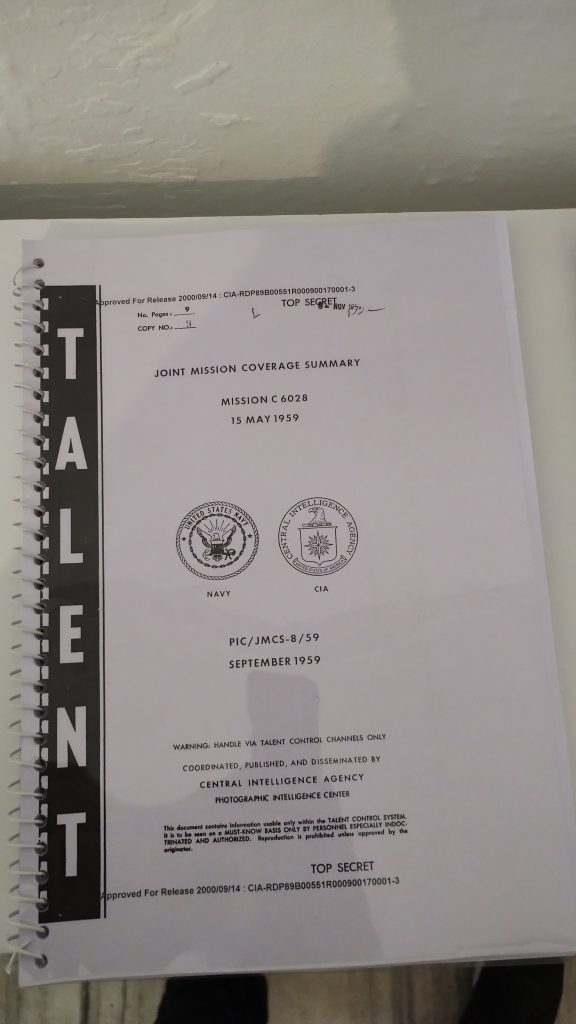

Sifting through photographs, letters, hand-drawn guerilla warfare manuals, declassified intelligence documents, one is confronted with multiple layers of a complicated history, wherein a nation’s individual struggle for independence gets entangled with the seismic shifts in the geopolitical terrain. Following China’s encroachment into Tibet in 1950, the CIA would launch the covert operation ST CIRCUS in 1956. Over the next few years, they would train around 250 Tibetans in an abandoned World War II-era military base in Colorado, named Camp Hale, which became an unlikely place of refuge for them.

Located amidst lush meadows and mountainous environs of the Rockies, the landscape reminded the recently exiled Tibetans of their home; they called it Dumra, ‘Garden’. This uneasy ‘paradise’, situated far from the conflict, was the site where Tibet’s entanglement with global affairs played out on a more intimate level. A contact zone that saw the coming together of hard-boiled American intelligence officers and ordinary Tibetans forced to take up arms, Camp Hale was an ambiguous, liminal space where national identities could be fluid and unlikely alliances could be formed. Codes of secrecy demanded that the Tibetans be assigned American monikers like Larry, Pete, Rocky. A photograph taken in Camp Hale shows them sitting together, wearing American clothes, sunglasses and each holding up a copy of Times magazine. In this ‘in-between’ space, barriers of nation, culture, identity, and tongue also dissolved, which allowed the American and their Tibetan compatriots to form deep bonds.

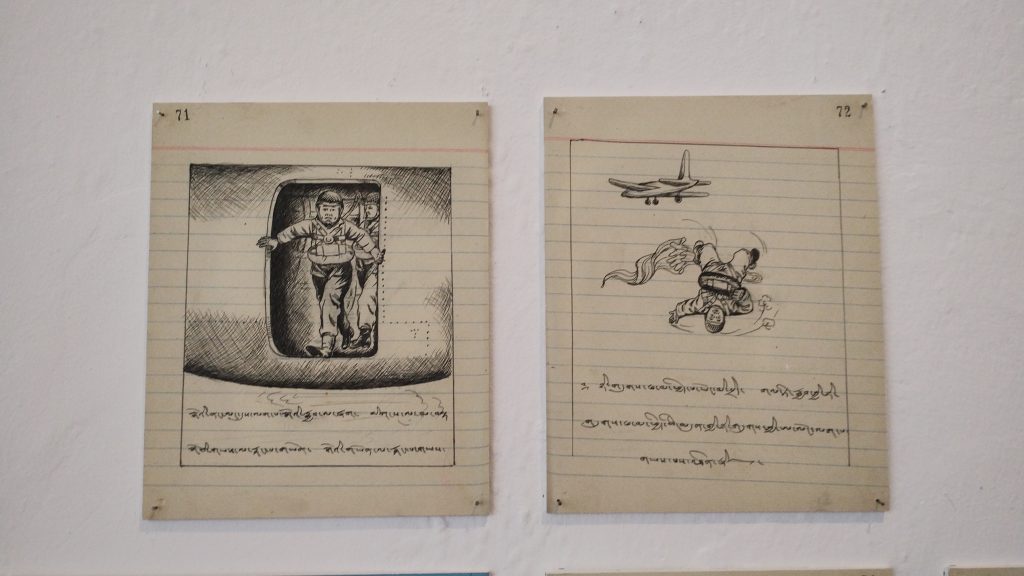

The highlight from this era are the artworks made by the Tibetans in Camp Hale as part of their art classes. The Americans encouraged art practice among the trainees for it was used to conduct their psychological assessment. They drew about their home as well the destruction they had witnessed when the Chinese army had attacked Tibetan villages – their works in crayon contain recurring images of bombs being dropped on monasteries and Buddha idols being demolished by the tyrannical Chinese military. The trainees also made propaganda caricatures at the behest of the Americans, that were circulated among the Tibetan public to foster anti-Chinese sentiments.

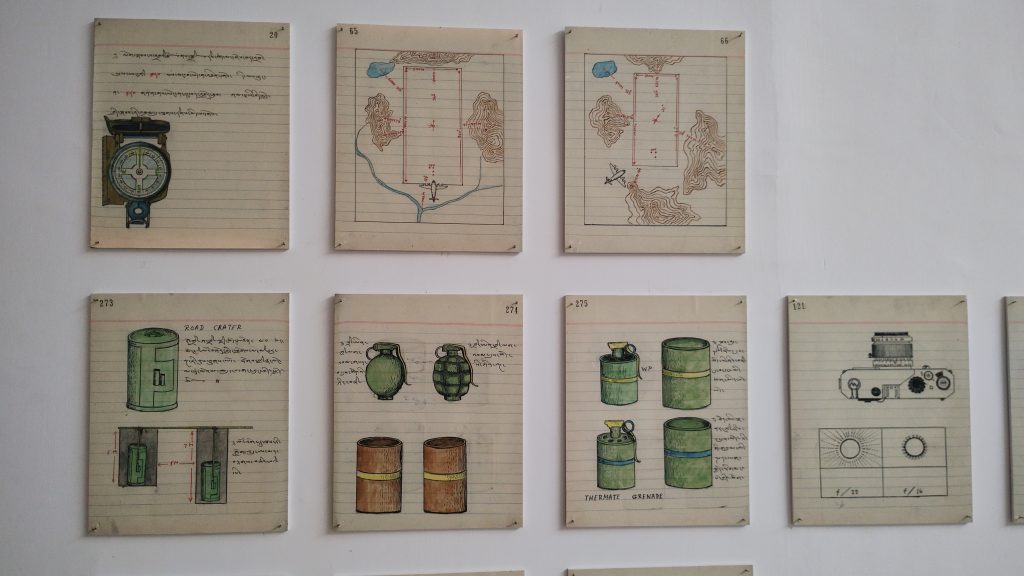

Another interesting artefact is a hand-made manual for guerilla warfare. Replete with intricately drawn and coloured models, diagrams and maps, it offers instructions on topics ranging from the structure of an SLR camera and hand-grenades to steps for creating a makeshift airstrip and even parachuting out of an aeroplane! The contents of the handbook reflect the diverse range of topics they were being taught – guerilla warfare, collecting intelligence, photography, parachuting, and even geography, mathematics and political science. What strikes out in the colourful pages is the conscientious effort invested by the artist despite the harsh circumstances that might have lived in. The illustrations were first drawn out in pencil, then water coloured and outlined in ink. Notwithstanding the fairly precise quality of the renditions, the artist also used hatchings and cross hatchings in ink to denote volume!

The Tibetans’ contact with Americans was also their first encounter with modernity. Those who had never seen an automobile before were now being trained in tactics of espionage and covert surveillance. When the trained operatives would be airdropped into Tibet, it would literally be a “leap of faith into the modern world” for them, as the curatorial note observes. Moreover, one must also be aware of the power hierarchy inherent to the American-Tibetan alliance. American support for Tibet’s sovereignty was not an outcome of an altruistic motive but rather America’s anti-communist global stance. The Tibetans could be used as expendable pawns for gathering intelligence, while the CIA would continue pulling strings from the shadows.

The airdrop missions were extremely hazardous. The curatorial note elaborates, “[The airdropped trainees’] mission was to organise the fighters into modern guerilla armies and coordinate arms drops for them with the CIA. Although some of the teams successfully linked up with these groups and the CIA dropped some weapons, the missions mostly ended in tragedy.” For Tibetans, the “leap of faith” into modernity meant a tryst with death. The operatives would be supplied with tsampa (roasted barley flour, staple in Tibet), manufactured by Kellogg’s, and cyanide pills to be consumed if captured. The antonymic nature of the two offerings, in a sense, encapsulates the contradictory impulses at play – American support was both life-giving and deleterious for the Tibetans.

Lhamo Tsering’s archive also furnishes a series of letters he received from his CIA handler between 1964-65. Dealing with day-to-day affairs like timely disbursement of funds, concern over inadequate supply of intelligence, struggles of finding a capable translator, the typewritten correspondences provide a glimpse into the mundanity in espionage operations. Tsering was at the helm of operational charge at the Tibetan resistance base in Mustang, a remote kingdom in the north of Nepal. In addition to planning military strategies, he was also in charge of reporting to CIA agents in Calcutta.

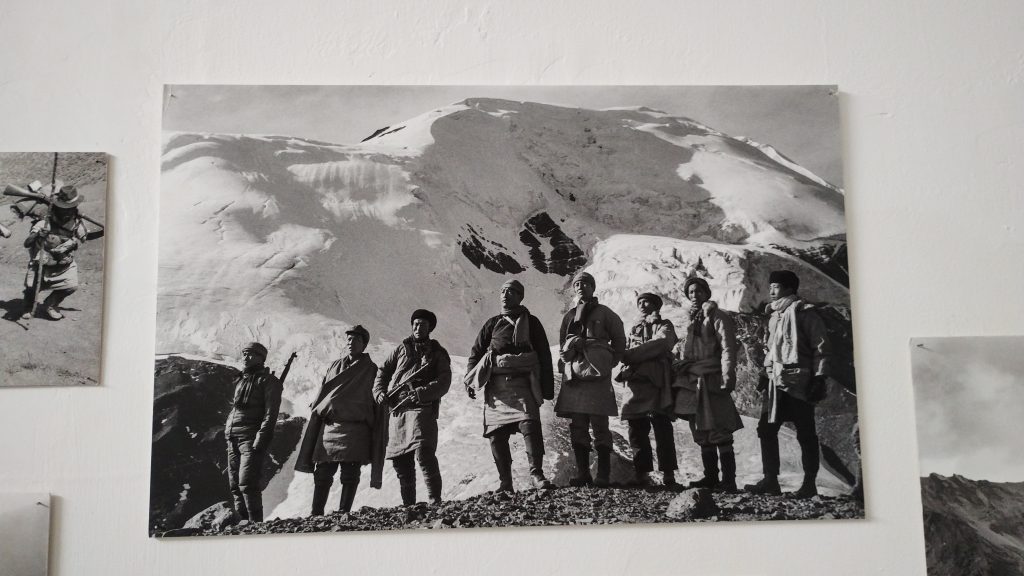

Also on display are a series of photographs documenting the lives of the Tibetan resistance fighters in the arid, mountainous terrain of Mustang. Another in-between location like Camp Hale, Mustang was chosen not just for its proximity to Tibet but also because its people share similar culture and traditions with Tibetans. The images show the fighters training, riding and even posing atop cliffs with their weapons. Some of these are idealised group photographs in which the men, consciously adopting a heroic stance, wield their weapons and gaze into the distance, with a mountainous expanse in the background. These orchestrated images may be read as self-fashioning strategies adopted by the resistance fighters to orient themselves and lay claim over an alien landscape.

courtesy: Author

Operation ST CIRCUS was quite abruptly terminated when, in 1969, US President Richard Nixon visited China. The Tibetan rebel fighters were left demoralised and feeling betrayed. Even the American agents, who were in solidarity with their Tibetan compatriots, felt cheated and let down by the change in policy of the US government. The resistance movement came to an end in 1974 when Nepalese troops surrounded Mustang and demanded their surrender.

The artefacts on exhibit in the Shadow Circus also demonstrate interesting tensions at play. The various declassified CIA reports and documents on ST CIRCUS, the labour of the paranoid bureaucratic machinery of intelligence gathering, are reflective of the US’ position as a shadowy global player working to further their geopolitical interests. In contrast, materials from Tsering’s archive are more personal and foreground the Tibetan perspective in this transnational encounter. Tenzing’s own intervention through his personal accounts inscribed on blue cardboard panels present an added layer to this play between multiple voices.

Lhamo Tsering never shared with his family the role he played in the Tibetan resistance movement. Tenzing would only come to know of his father’s covert activities when Tsering was arrested in 1974 by the Nepalese army. In fact, this haunting silence regarding the history of resistance was common to most veterans. In absence of retellings, the tales of sheer determination and immense fortitude gradually faded from public consciousness, even in Tibet, resulting in what Carole McGranahan has termed “arrested histories”: “Resistance history was arrested, meaning that its telling was postponed until an indeterminate time in the future when it would be safe or beneficial to tell it.” * Families of many veterans only came to know of their involvement decades later, when McGranahan interviewed them.

Yet, in Tsering’s case, the silence was in a sense compensated by his obsessive archiving. Storing thousands of photographs, maps, intelligence documents and letters, this archiving instinct was in direct violation to strict codes of secrecy; in a strange twist, the very archive, which was detrimental to the interests of the resistance movement, manages to fill the void in public memory in posterity. Tsering was released from prison seven years later in 1980, following which he served as a respected minister in the exiled government of Tibet in India. Using the archive he had gathered, he would later write an account of the resistance in a monumental eight-volume work titled Resistance. When Tenzing and Ritu visited occupied Tibet in the 1990s for shooting their documentary A Stranger in My Native Land (1998), Tsering drew for them a map of his ancestral village. Even though it had been 50 years since he had left his village, its topographic contours were etched vividly in his memory.

Tenzing and Ritu’s exhibition is reflective of their decades-long engagement in recuperating these “arrested histories”. While foregrounding uncomfortable questions plaguing the Tibetan predicament – on issues like exile, belonging and the impossibility of returning to one’s home – it most importantly demonstrates the potency of the act of remembering in reclaiming histories, and perhaps even the lost homeland. Tibet will continue to survive through retellings, nostalgic reminiscences, topographic renditions recalled from memory and the archive of relics from a failed, yet significant, rebellion.

Shadow Circus: A Personal Archive of Tibetan Resistance (1957-1974) will be on display at the School of Arts and Aesthetics Gallery, 10 am-6 pm everyday between 16 February-15 March 2024.

Reference:

Carole NcGranahan, Arrested Histories: Tibet, the CIA, and the Memories of a Forgotten War (2010)

Young Artists on the Rise: Yuva Sambhav Exhibition Highlighted Amid Grant Awards

Contributor