Niveditha Ajay

The city of New York is iconic for its history, legacy, and sheer diversity. When imagining the bustling metropolis with its magnificent skyscrapers and crowded subway, one cannot forget the irreplaceable role street art has had in the making of its exterior. With graffiti, murals and blatant political imagery all meshed together- this art has a fantastic history of its own that begins in the early nineteenth century and has evolved into the revered style it is today. Several pioneering individuals contributed greatly, working to traverse bias and vandalism to promote activism, expression and artistic standard using the world (literally) as their canvas.

There are several different accounts of the origin of street art, owing to the variety of definitions the umbrella term has acquired. A popular understanding of the term is that it includes works done in public spaces often without official permission. Hence, tagging, graffiti, cartoons, chalk art, installations and work done on trains can all be part of this history. Evidence of street art in the city and nearby regions goes as far back as the 1920s-1930s, with certain sources identifying the immigration of new cultures into the city contributing to the unconventional mode of art. However, eventually, gang culture and territoriality overtook the form aggravating institutional disfavour towards the same. This period saw what has now come to be known as primitive graffiti, and name-based artwork.

Aaron Douglas

Source: Widewalls

The 1930s and 1940s in the city of New York were characterised by the Harlem Renaissance, a period of Black writers and artists convening to rejuvenate, explore and experiment with their media, in the Harlem district. This very significant movement contributed to some of the most exquisite murals still displayed in parts of the city today. Aaron Douglas’ Aspects of a Negro Life is a renowned piece of the time- drawn across four panels, featuring the history of Black people, their culture, slavery and emancipation. The mural is present in the New York Public Library. Charles Alston painted murals that took inspiration from Black fairy tales, African American diaspora and livelihoods, as well as folktales- for the Harlem Hospital, in 1936. It is important to note that most works of the period were commissioned or done with official permission contrary to the popular understanding of street art culture.

Source: Paradigm Gallery+ Studio

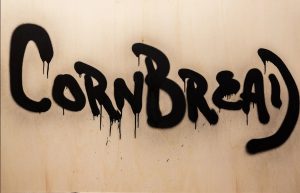

Graffiti and name tagging find their roots in 1960s Philadelphia, with Cornbread being widely known as the first modern graffiti artist. With others like Cool Earl, this time saw graffiti that involved black markers alone, and the work itself was the signing of their names in public spaces. Eventually, other artists like Topcat- 126 and Taki-183 started doing the same in the city, with the challenge being to see how many public spaces an artist could sign their name on. The subway and freight trains that were widely accessible to the public too became ideal canvases for their art. Tracey-168 and Cliff-159 were among the earliest to start using coloured images in graffiti, with the introduction of colour spray. Brooklyn and the Bronx were some of the centres of graffiti art in the 60s and 70s. The styles developed during the time involved the use of the now-popular bubble letters and the Broadway Elegant font. Due to their ability to be quickly made, they were popularly referred to as “throw-ups”.

Images by Martha Cooper

Source: Amazon

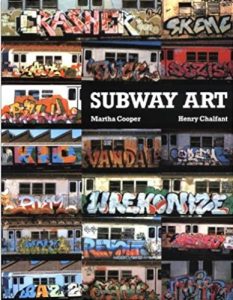

The 60s and 70s have now been recognised as the “Golden Age of Graffiti” where institutional pushback towards the work was also combatted. Mayor John Lindsay was the first to openly begin policies against graffiti and street art owing to their growing association with vandalism and crime. Work on public buildings and especially trains was strictly restricted or prohibited with heavily drawn train cars being replaced completely by 1989. Paradoxically, there was a simultaneous movement to recognise and preserve the wondrous form. Martha Cooper, a photographer, began documenting and compiling collections of street artists and their movements and was part of the larger initiative to recognise the fine art form for what it was. She published a collection of these titled Subway Art which is now one of the most influential and widely referred to pieces on street art and graffiti. Cooper distributed copies of these books during the 1980s and is still an active graffiti photographer today. The period also saw a rise in the work of women artists such as Lady Pink, often known as the “First Lady of Graffiti”. Her endorsements, activism and work over the years have led to the active participation of women in the form. Active from the early 1980s, she created the first all-women graffiti crew titled Ladies of the Arts.

Lady Pink

Source: LadyPinkNYC

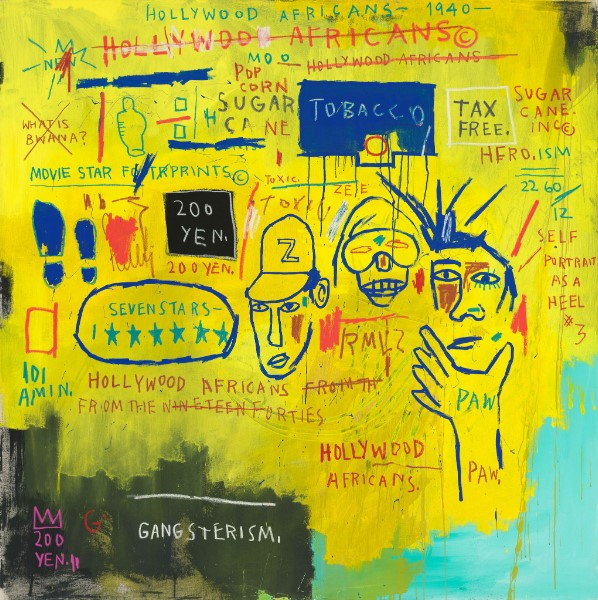

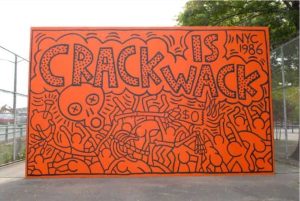

The 1980s saw a successful effort at inviting graffiti art into museum and gallery spaces. Photographers, activists, and curators who saw the purpose and message of street art as above the claims of public defacement were responsible for this transition. Keith Haring was an influential artist of the 80s who used his art to advocate against substance abuse as well as to raise awareness for the AIDS epidemic. His innovative pieces that manipulated visual language using chalk and flat, cartoon images attained widespread critical acclaim. Jean Michael Basquiat was only 20 years old when he began doing art on the streets of New York, with an expert hold over abstraction and figuration. His pieces focused on calling out systemic racism, the Black experience and classism in American society. These concerted efforts led to the widespread popularity and acceptance of graffiti and street works as holding a place in the history of art. To date, these forms remain popular among artists across the world, with cities like Berlin and London being other centres of graffiti and street art. Active artists like Lady Pink, Banksy from London with their politically relevant graffiti, or Blu from Bologna whose work showcases socio-political realities are all inspirations to the next generation.

Keith Haring

Source: Artland Magazine

New York City street art is a story of resilience and a single glance at its history proves it. Originating from cultures that face persecution even today, with artists from marginalised groups at the forefront – street art is a tale of persevering in adversity, even when institutions work to quell the messaging or control the facades of buildings that belong to all. While the aim is not to endorse criminal activity, it is important to never lose sight of the wonderfully rebellious, skilled craft that is the true nature of street art.

SOURCES:

https://eportfolios.macaulay.cuny.edu/generaladmissionnyc/2018/05/06/the-history-of-graffiti/

https://www.widewalls.ch/magazine/the-history-of-street-art

https://magazine.artland.com/street-art/