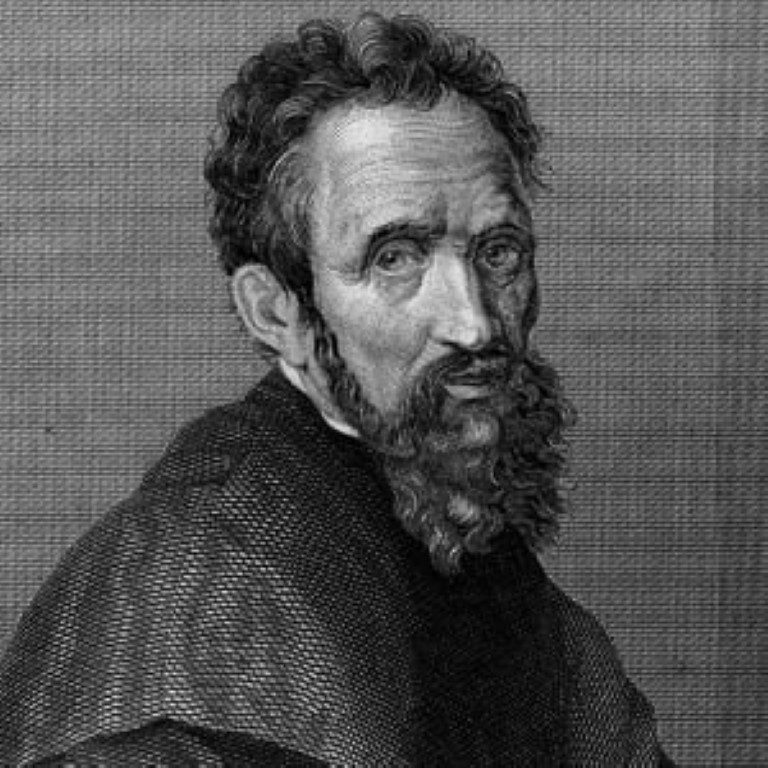

Birth During the Paris Commune

During the chaotic “Bloody Week” marking the end of the Paris Commune, Georges-Henri Rouault was born in a cellar on May 27, 1871. After an unguided missile hit the family home, the pregnant mother was forced to deliver her child underground. Rouault, a weak and delicate child, had a joyful upbringing in Belleville, an industrial district of Paris. He inherited his father Alexander’s love for artisanal work; Alexander was a carpenter at the Pleyel piano factory.

Courtesy – The Collector

The Rouault family embraced imagination and supported Georges’s artistic path. His maternal grandfather had collected lithographs by Honoré Daumier and reproductions of Rembrandt, Courbet, and Manet. Rouault acknowledged beginning his artistic education with Daumier’s works.

Early Apprenticeship and Artistic Education

Rouault’s passion for art emerged early. At age fourteen, he apprenticed with Georges Hirsch, a medieval window restoration and glass painting specialist. The black lines central to Rouault’s adult style are often linked to this experience. On Sundays, he visited the Louvre to sketch. At eighteen, he joined the Paris School of Fine Arts. Studying under Gustave Moreau alongside Marquet, Camoin, and Matisse, Rouault formed a strong bond with his instructor.

Courtesy – ArtsDot

Moreau was a supportive and modern teacher, encouraging students to explore their individuality and symbolism in painting.

Rising Career and Symbolist Influence

With Moreau’s encouragement, Rouault began exhibiting publicly. At 23, he received the Prix Chenavard for L’Enfant Jésus parmi les docteurs (Infant Jesus among the Doctors). In his early years, Rouault followed conventional subject matter and employed a Symbolist style, which he later moved away from. After his second failed attempt at the Prix de Rome, he followed Moreau’s advice and left the École des Beaux-Arts, diverging from its academic methods.

Courtesy – Flickr

Transition Toward Fauvism

Around 1898, Rouault faced a psychological crisis, finding new inspiration in Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Cézanne. This led to a stylistic shift aligning with Fauvism, known for bold and arbitrary colour use, by the 1905 Salon d’Automne. Before World War I, he excelled in creating expressive paintings in watercolour and oil on paper, using vivid blues, bold shapes, dynamic lighting, and expressive brushstrokes.

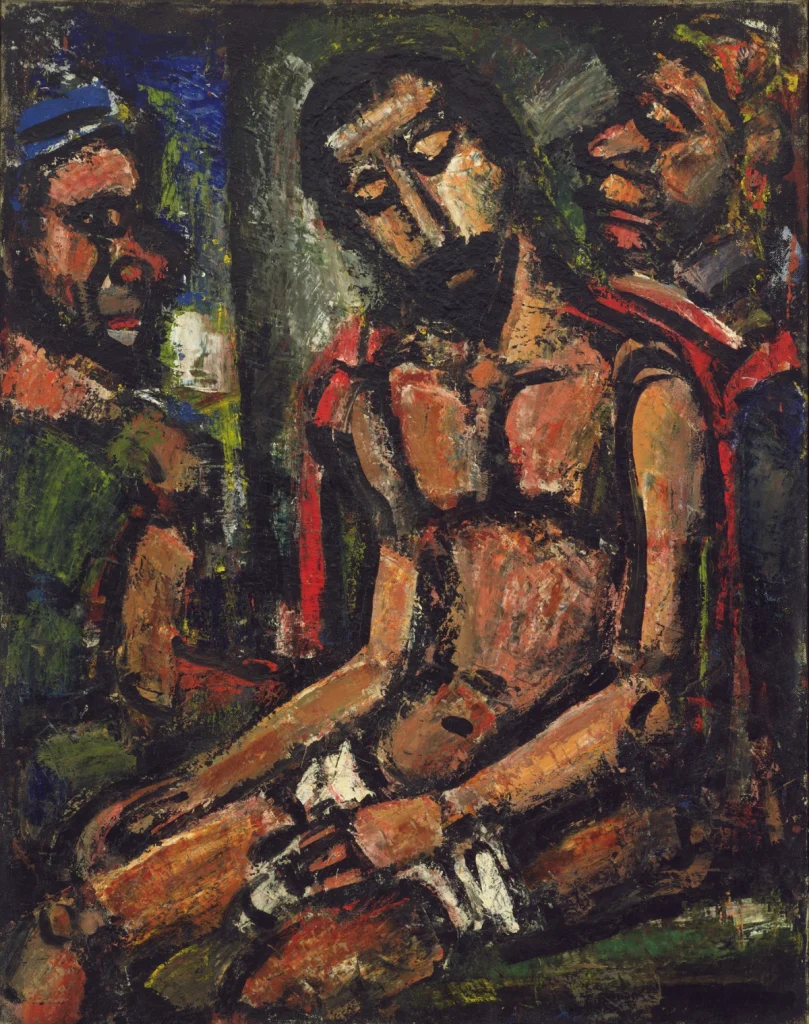

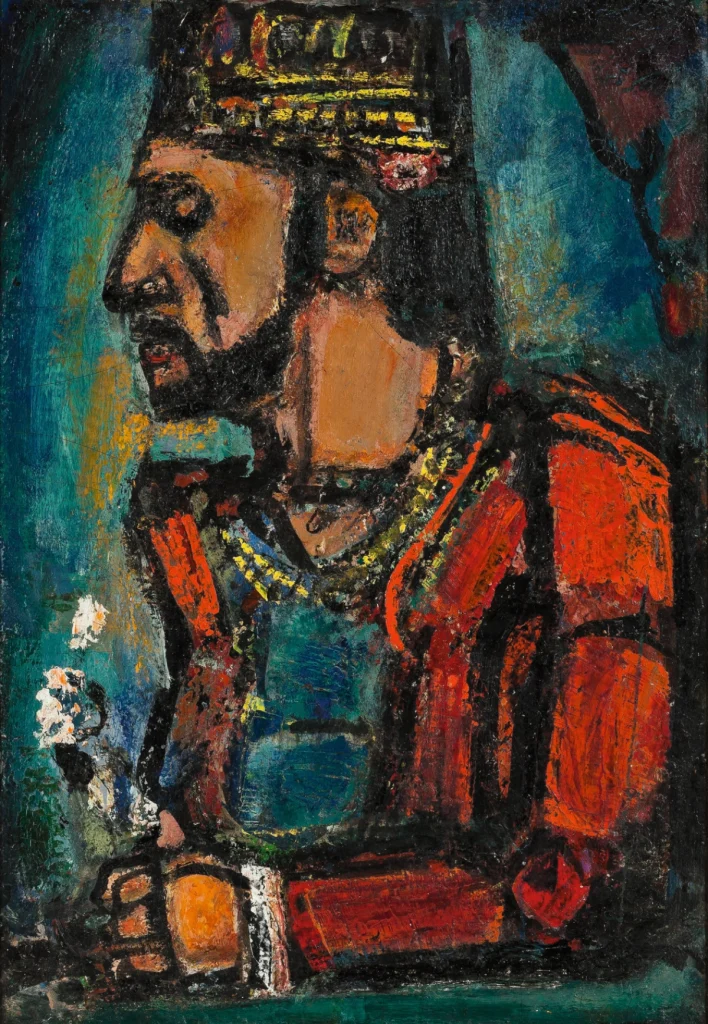

Post-1914, Rouault began favouring oil paints, developing a rich texture through layered application. His forms became heavier and simplified, enhanced by vivid colours and thick dark outlines resembling stained glass. His focus shifted to religious themes, particularly on the idea of salvation.

Religious Themes and Major Works

In the 1930s, Rouault painted a powerful series on the Passion of Christ. Key pieces include Christ Mocked by Soldiers, The Holy Face, and Christ and the High Priest. He often revised past works, as seen in The Old King, dated both 1916 and 1936. Unlike many modernist painters, Rouault’s work was rooted in deep Catholic belief. He used symbolic and vibrant colours to communicate religious principles, a method seen as outdated within progressive artistic circles.

Courtesy – Museum of Modern Art

Expression of Faith Through Art

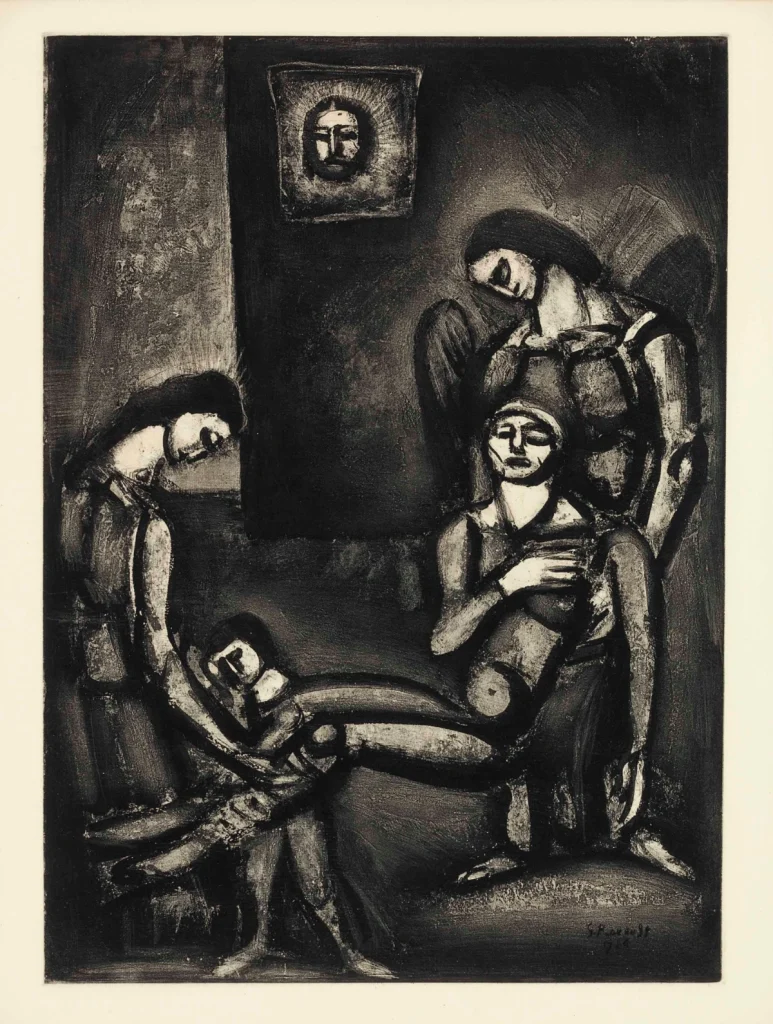

At a time when faith was seen as naive, Rouault portrayed Jesus not with irony but as humanity’s true redeemer. His magnum opus, Miserere (1922–1927), comprises 58 illustrations reflecting human suffering in the style of German Expressionist woodcuts. Christ appears as the saviour of despairing souls, exposing the harsh realities of suffering through spiritual art.

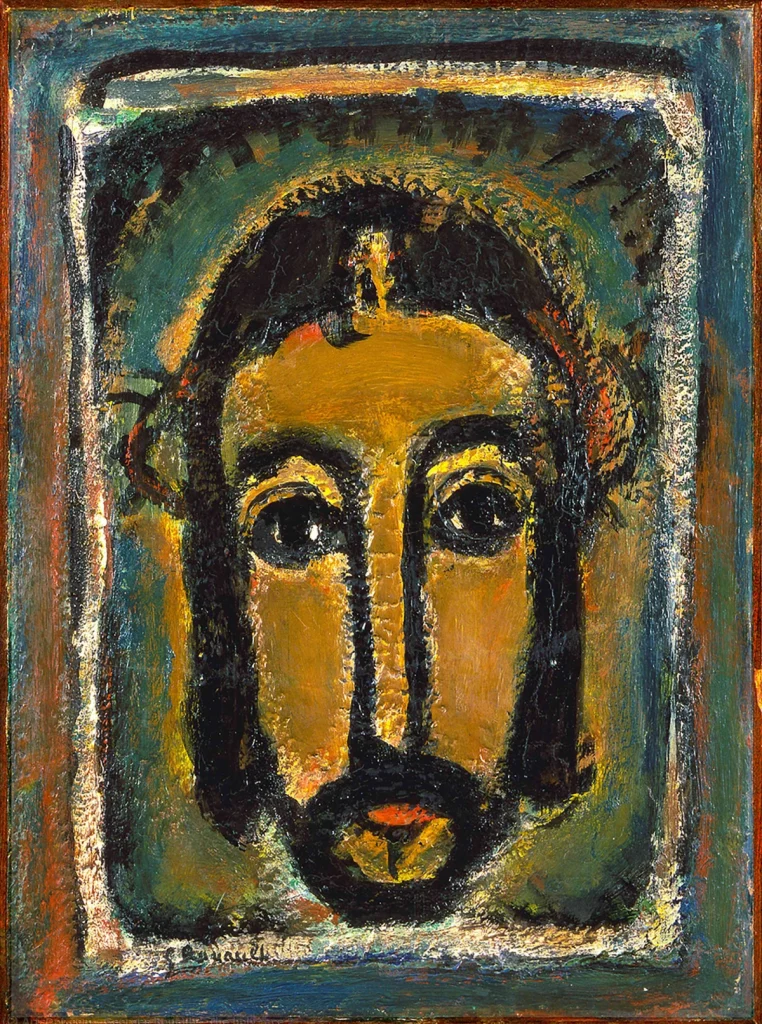

Signature Style of Religious Portraiture

Rouault painted many portraits of Christ, characterised by heavy black lines and warm, muted hues. The thick contours highlight Christ’s visage and outline a subtle glow of light. These religious paintings used natural skin tones and emotional intensity, particularly through the eyes and the tilted head, emphasising the intelligence and humanity of Christ.

Courtesy – The Philips Collection

Rouault’s Unique Place in Modern Art

Though a contemporary of the Cubists, Fauvists, and Expressionists, Rouault did not align with any single movement. His unique style of religious painting kept him apart from mainstream modernism. Critics like Clement Greenberg dismissed his work; in 1945, Greenberg labelled him an odd representative of Catholicism, influenced by Léon Bloy’s passionate and avant-garde ideals. Rouault was not fully embraced by modernist circles nor by traditional religious critics, who saw his style as unorthodox.

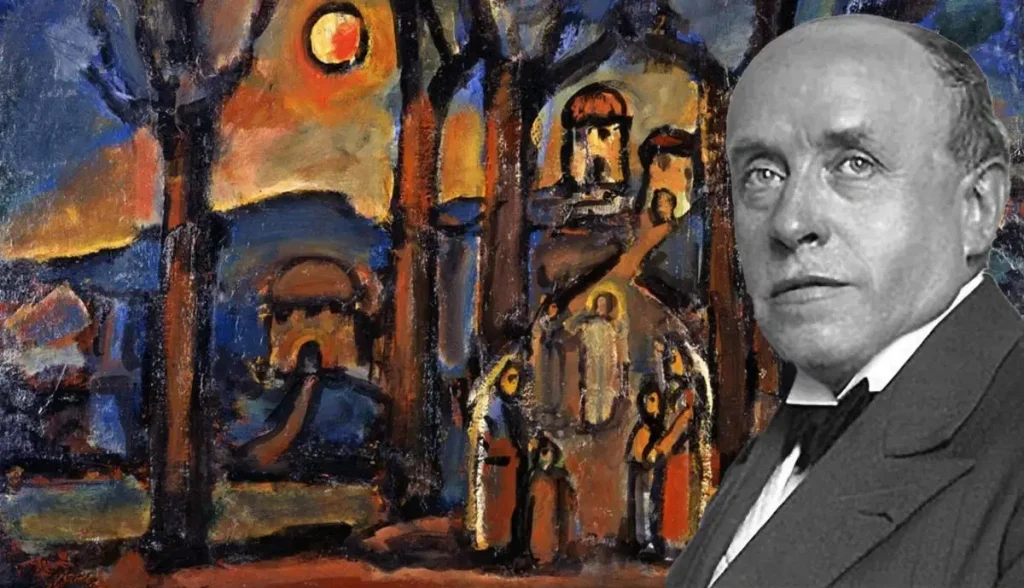

Biblical Landscapes and Later Works

In his later years, Rouault created works known as Biblical Landscapes or Landscapes with Figures. These compositions featured architectural settings and figures framed by trees. The figures, often unidentified, were centrally placed and possibly symbolic of Christ and his disciples. These paintings merged a symbolic landscape with simple techniques and a strong spiritual essence. Elements like warm browns and greens, flat shapes, pure colour, and thick black outlines marked his later period.

Courtesy – Carnegie Museum of Art

Spirit of Peace in Rouault’s Landscapes

Each of Rouault’s later landscapes, influenced by his religious conviction, radiated peace and tranquillity. The clothing suggests ancient times, and although specific Biblical narratives are not named, the imagery implies a connection to the life of Jesus. He fused classical influences with symbolism to achieve spiritual clarity in modern art.

Suarès’ Influence and Spiritual Counsel

At the beginning of Rouault’s career, poet and critic André Suarès encouraged him to embrace the spiritual “mystery melody” within. Suarès followed this advice throughout his own creative life. This encouragement further validated Rouault’s commitment to spiritual and religious art, setting his work apart from the prevailing trends of modernist detachment and intellectualism.

Courtesy – Christie’s

Personal Loss and Artistic Seclusion

The death of Gustave Moreau in 1898 from cancer was a profound blow to Rouault. He described this period as “the abyss.” With the loss of his emotional support and the relocation of his family to Algeria, Rouault underwent a deep ethical and artistic crisis. This period of seclusion left a lasting mark on his personal life and creative journey.

Image – Georges Rouault. Biblical Landscapes with Two Trees (1952). Courtesy – Museum of Modern Art

Contributor