Introduction

The age-old debate of whether one can separate the art from the artist remains a topic of fervent discussion, touching upon ethical, moral, and aesthetic dimensions. This essay delves into the various perspectives surrounding this issue, examining instances where the art and the artist’s personal life intersect or diverge.

1. The Aesthetic Disconnect

A fundamental argument in favour of separating art from the artist rests on the belief that the intrinsic value of a work of art exists independently of the creator’s life. For example, consider the captivating works of Vincent van Gogh. His tumultuous personal life, marked by mental illness and social isolation, is well-documented. However, his vibrant, emotionally charged paintings like “Starry Night” evoke emotions in viewers regardless of their knowledge of his biography. This perspective underscores the idea that art can stand on its own, transcending the limitations of the artist’s experiences.

2. Ethical Considerations

Conversely, proponents of not separating the art from the artist emphasize the ethical implications of endorsing art that might indirectly condone reprehensible behaviour. A pertinent case is that of director Roman Polanski. His films, known for their cinematic brilliance, are lauded by many. However, his criminal history involving sexual assault raises questions about whether supporting his work indirectly supports his actions. This viewpoint underscores the interconnectedness of art and the artist’s moral compass.

3. Contextualising Historical Works

The question of separation becomes more intricate when considering historical artworks. The societal norms, prevailing ideologies, and cultural contexts during an artist’s time can significantly influence their creations. Take for instance the works of Renaissance artists who often portrayed religious themes. Their art was deeply tied to the dominant religious values of their era. While modern audiences might disagree with certain aspects of these beliefs, recognising the historical context can help appreciate the art without necessarily endorsing the entire belief system.

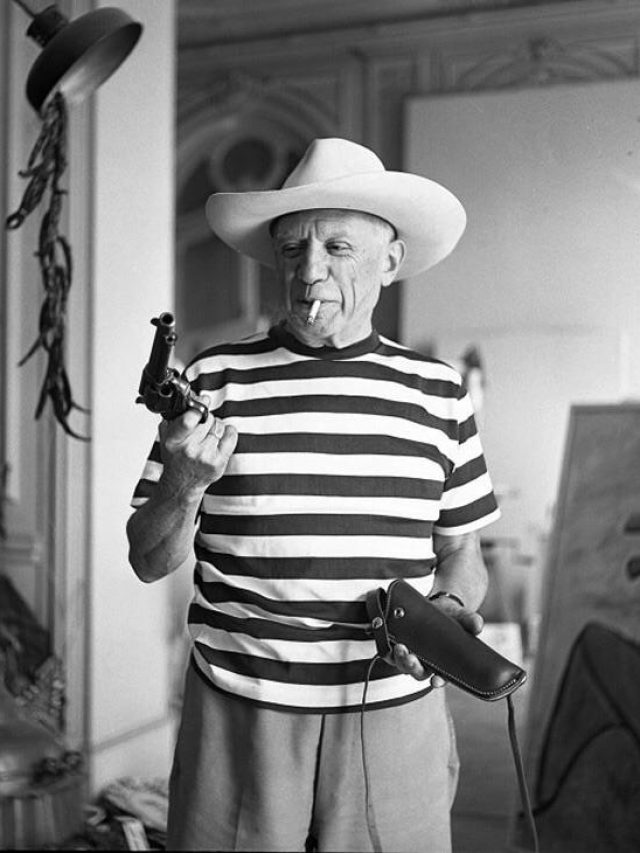

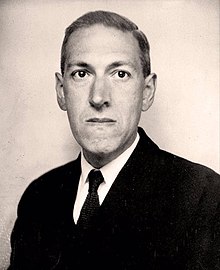

4. The Severity Spectrum

The degree of separation can vary based on the gravity of the artist’s actions. In some instances, artists may engage in unrelated acts that do not directly intersect with their creative output. Consider the literary genius of HP Lovecraft, whose pioneering works in the horror genre have left an indelible mark. Yet, his xenophobic and racist views are disconcerting. Here, separating the art from the artist might be more feasible, as the offensive statements do not directly inform the themes of his stories.

5. The Power of Personal Choice

Ultimately, the decision to separate art from the artist often hinges on personal convictions. Some might choose to engage critically with both aspects, using the art as a platform to discuss the artist’s flaws. Others might reject the work entirely, finding it untenable to support an artist whose actions conflict with their values. This choice reflects the diverse ways in which individuals navigate the intricate terrain between art and ethics.

6. Navigating the Middle Ground

An alternative approach involves critically engaging with both the art and the artist. By acknowledging the artist’s problematic behaviours while also examining the artistic merits, a more nuanced understanding can emerge. For instance, the poetry of Pablo Neruda is celebrated for its evocative imagery. However, acknowledging his alleged involvement with political repression opens doors for broader conversations about the complexities of human nature and art’s role in reflecting society’s nuances.

7. Editor’s Take

In the ever-evolving landscape of artistic interpretation, the post-modern argument that “there’s nothing outside of the text” assumes a profound significance. As we engage with works of art, we find ourselves confronted with a compelling perspective: separating art from the artist. This stance encourages us to adopt a viewpoint that transcends the traditional boundaries of authorship, diving into the depths of the art itself. Through this post-modern lens, the concept of the author’s death takes center stage, enriching our understanding of art in ways that defy conventional wisdom.

The notion that “there’s nothing outside of the text” asserts that the meaning of a work of art resides solely within its intrinsic components. When applied to the discussion of art and its creators, this perspective compels us to disconnect the creator’s personal life from their creations. The artist’s identity, intentions, and biography recede into the background as we engage with the artwork on its own terms.

One crucial manifestation of this principle is the idea that “the author is dead.” Coined by Roland Barthes, this phrase encapsulates the belief that once a work is released into the world, it takes on a life of its own. The artist’s subjective intentions no longer hold sole authority over the work’s interpretation. Rather, readers, viewers, and audiences are invited to bring their unique perspectives, experiences, and emotions to the table. This results in a dynamic interplay of meanings, where the art becomes a canvas for a multitude of narratives and reflections.

The post-modern argument in favour of separating art from the artist offers a liberating framework, untethering us from the constraints of biographical fallacy. This fallacy assumes that an artist’s personal life inherently determines the meaning of their work. In contrast, the post-modern approach encourages us to examine the work’s internal complexities, exploring its themes, symbols, and structures, independent of the artist’s background.

Moreover, this stance liberates art from the burden of moral judgment against its creator. It acknowledges that art’s value extends beyond the ethical considerations of its originator. Art becomes a vehicle for collective imagination, cultural discourse, and emotional resonance. By divorcing the art from the artist, we foster a space where appreciation is not overshadowed by personal biases or judgments.

Critics of this viewpoint might argue that it dismisses the significance of context and historical understanding. However, the post-modern perspective does not necessarily negate the importance of these elements. Rather, it shifts the focus from a unilateral understanding dictated by the artist’s biography to a multidimensional exploration that includes a range of contextual factors.

Embracing the post-modern argument of separating art from the artist aligns with the ethos of a diverse, ever-evolving artistic landscape. As we engage with art, we are invited to explore its nuances, meanings, and potential through the lens of our own experiences and interpretations. In this paradigm, the artist’s death does not signify a loss, but a liberation—a freeing of art from the constraints of individual identity and a celebration of its capacity to resonate with the kaleidoscope of human perspectives.

Conclusion

The question of whether one can separate the art from the artist transcends a simple binary. It invites us to wrestle with moral dilemmas, historical contexts, and personal beliefs. As society evolves, so too will our perspectives on this matter, as we continuously grapple with the intricate interplay between creativity and the human condition. In our pursuit of understanding and appreciation, we are compelled to navigate this complex terrain with sensitivity, introspection, and an openness to diverse viewpoints.

Iftikar Ahmed is a New Delhi-based art writer & researcher.