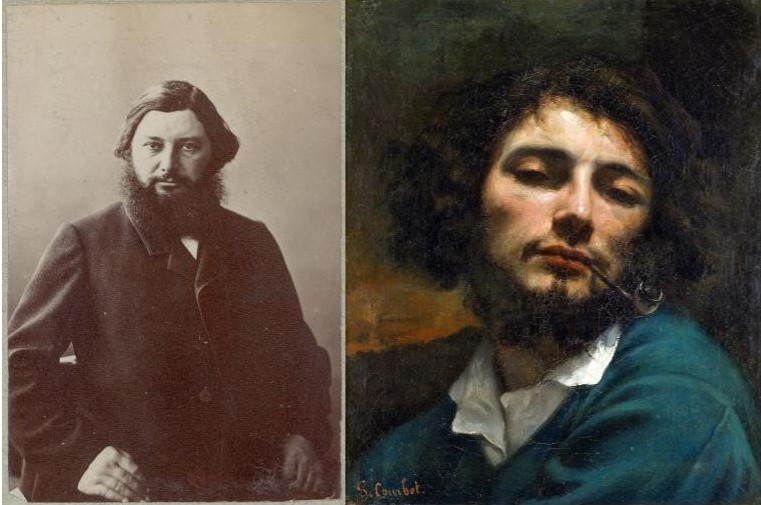

Gustave Courbet, the “proudest and most arrogant man in France,” is the founding father of the politically-motivated Realism campaign, revolutionising the European art setting. Gustave created a sensation at the Paris Salon in 1850-51 with his paintings portraying his native Ornans. In Paris Salon, Courbet questions the visual narratives of history and realistic painting with his paintings rendering scenes from the daily life of the village people, which blends life in time and space. The Stonebreakers (1849-50) and A Burial at Ornans (1849-50) make visual riots in the French art scene.

I have studied the art of the ancients and the art of the moderns, avoiding any preconceived system and without prejudice. I no longer wanted to imitate the one than to copy the other; nor, furthermore, was it my intention to attain the trivial goal of “art for art’s sake”. No!…To be in a position to translate the customs, the ideas, the appearance of my time, according to my own estimation; to be not only a painter, but a man as well; in short, to create living art – this is my goal. – Gustave Courbet, The Realist Manifesto, 1855

Considered a creator, he paved the way for the Impressionists and, eventually, the birth of contemporary Western art, known for its manifesto paintings. People are trying to establish their reputations in every field related to art history, just as Courbet did in antiquity as one of the pioneers of the realistic movement. The period of Courbet’s life and work is essential to French social and artistic history because it saw intense political censorship of the arts, during which the government closely monitored the production of new works of art and their public exhibition.

Everything was censored; the government had complete control over many writers and artists, and anyone who protested faced fines or even jail time. While some accepted this monitoring of artistic expression, others saw it as a challenge and a chance to express themselves appropriately and convey their critical perspective via their work. According to some academics, Courbet attempted to break free from the conventions of the day to depict reality in all its raw, sensual, and authentic forms. Any proof that the triadic alliance he had assembled convinced his audience that Courbet’s work achieved the goals of Realism would have delighted him.

Known for his early 19th-century attitude against academic convention and Romanticism, Gustave Courbet (1819–1877) only painted what he could see. The rebelliousness of Courbet’s paintings at the time helped inspire new painters. Courbet’s intrusion of Realism serves as the foundation for Impressionism and Cubism. He also encouraged artists to use their artwork to describe social reality visually.

In Courbet’s day, religious morality established the theme and rules for painting. It was popular back then to discuss how Gustave Courbet explored spiritual ideas in his works, such as his nude paintings. In his paintings, Gustave Courbet frequently depicts ordinary peasants and labourers, typically of a less obviously political character. Art is not so much a painting or a canvas frame as it is an experiential process of creation and conception. Life is shown in the picture as a bohemian symphony highlighting other people’s importance.

In the book, The Rape of the Masters, Roger Kimball write about art and a chapter devoted to Courbet titled ‘Psychoanalyzing Courbet’. Roger Kimball writes about Courbet: Courbet was largely—I was going to say “self-taught,” but that is not quite right. He didn’t go in much for formal schooling of any kind. But he had many art teachers. He found them on the walls of the Louvre, in galleries in Holland, and, to a lesser extent, on his several visits to Germany in the early 1850s, where he encountered the work of the Realist painter Adolf Menzel (1815–1905). For Courbet, as for so many artists, imitation was an integral part of formation. By copying, he became who he was. Particularly important were the Spanish masters Diego Velázquez (1599–1660) and Francisco de Zurbarán (c. 1598– 1662) and some classic Dutch painters, especially Frans Hals (c. 1582–1666).

As many concepts and genres as possible flooded Courbet’s canvas: portraits, exhilarating seascapes and landscapes, lauded vignettes from the village and nudist scenes, sculptures, and so-called proletarian genre paintings; Courbet adds the fundamental component of art, a dramatic visual, and the genuine beauty of life to any medium. By removing politics from the mythological background of 19th-century painting, Courbet allows artists to express themselves freely. He is considered a founding father of modern art since he disapproved of any depictions of made-up or imaginary imagery. Art historians contended that Courbet’s sensual nudity, which carried political and societal criticism, had never been displayed before.

Courbet’s paintings were vital to French culture because of the intense political restriction of the arts in France during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. During Courbet’s time, there were laws and censorship governing art, and he frequently rebelled against the “governmental” and “church” organisations who supported ridiculous ideas for art. When Courbet began painting in the middle of the 1800s, pornography had not yet been established. Courbet received a lot of criticism because his paintings blended social class and social allegory. Following his constant reaction to France’s political unrest, Courbet went to Switzerland, where he passed away.

It is challenging to deny Courbet’s reputation and influence on nineteenth-century French art because he depicts social realities and issues in works like The Stonebreakers (1849), Burial at Ornans (1849–1850), and The Artist’s Studio: A Real Allegory Summarising A Period of Seven Years of My Life as an Artist (1854–1855). The reason is that Courbet used a creative comparison to oversee each figure, labouring over them all and turning his back on a nude model—a symbolic representation of academic activity. In the 1850s, Courbet was fascinated with nude female paintings and canonical subjects. His background in female figure illustration was limited, but every artist who wants to incorporate figures must have a general awareness of the human body. The women that Courbet portrayed were scandalous representations of women in the modern day rather than the idealized images of women that are typically found in art.

By eroticizing everyday people, Courbet conveyed notions of equality without overtly political themes and never attempted to hide the flaws in his depictions of ordinary people. Art historians are usually curious whether Courbet intended a dual meaning for his paintings. His paintings frequently employ a symbolic technique that questions viewers’ preconceived notions about how to see art.

What is the main query in “The Painter’s Studio: Real Allegory Determining a Phase of Seven Years of My Life as an Artist”? Because of its intriguing symbolic elements and philosophy, this picture has been the subject of extensive Western analysis for a long time. According to academics, Courbet’s embodiment of the object of centre in painting is demonstrated by this painting. The studio is depicted in this painting as a place not only for artists but also for society and the passage of time, showing creativity and revealing—even asserting—something about its manufacture.

Like The Artist’s Studio, Courbet’s previous work, Ornan’s Burial, used pictures of actual locals. Scholars have argued that The Artist’s Studio can be read non-algorithmically as a work that highlights the most remarkable aspects of Courbet’s much-vaunted technical ability, including his ability to work from memory and the virtuosity with which he wielded a palette knife and brush. In it, he combined generic depictions of figures with portraits of some of the residents of Ornans. During the artist’s lifetime, his reputation for having these attributes was so excellent that people would visit his studio to watch him paint.

Remembering Gustave Courbet, the fore-runner of the Realism Movement, on his birthday

Krispin Joseph PX, a poet and journalist, completed an MFA in art history and visual studies at the University of Hyderabad.