American modern artist Henry Taylor is well-known for his installations, sculptures, and paintings. Taylor, born in Ventura, California 1958, focuses on the African American experience in his art by frequently portraying situations from daily life. His paintings are notable for their immediacy, bold colours, and free brushstrokes.

In addition to celebrities, friends, and family, Taylor’s subjects frequently touch on racial, identity, and social justice issues in his artwork. His painting of Obama won him a lot of praise, and it was featured in the 2017 Whitney Biennial. Taylor’s artwork has been shown in many galleries and museums across the globe, such as the Tate Modern in London, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles. His reputation as one of the top contemporary painters working today has been cemented by the numerous accolades and honours he has garnered.

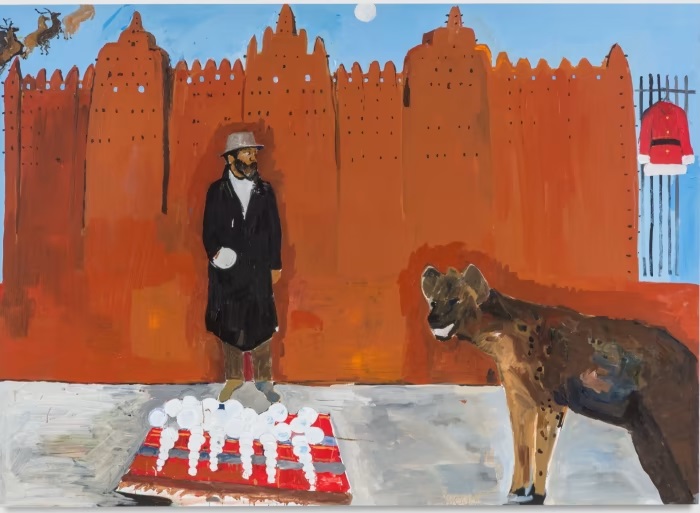

Henry Taylor has been depicting individuals from a broad spectrum of backgrounds—friends, neighbours, family members, celebrities, politicians, and strangers—for more than thirty years with a combination of sensitivity and raw immediacy. The title of this show, B Side, alludes to the side of a record album that frequently comprises lesser-known, more experimental music and his improvisational approach to artmaking.

Critics have characterized Henry Taylor in various ways, including activist, social realist, genre painter, portraitist, and outsider. Taylor’s deceptively simple subject matter—he is best renowned for his portrayals of African-American personalities and his concentration on the marginalized and the everyday—probably explains why people insist on giving him a label. But it’s evident from the Los Angeles artist’s expansive hometown retrospective at Moca, B Side, that such generalizations miss his work’s visionary, mystical, and expressive aspects.

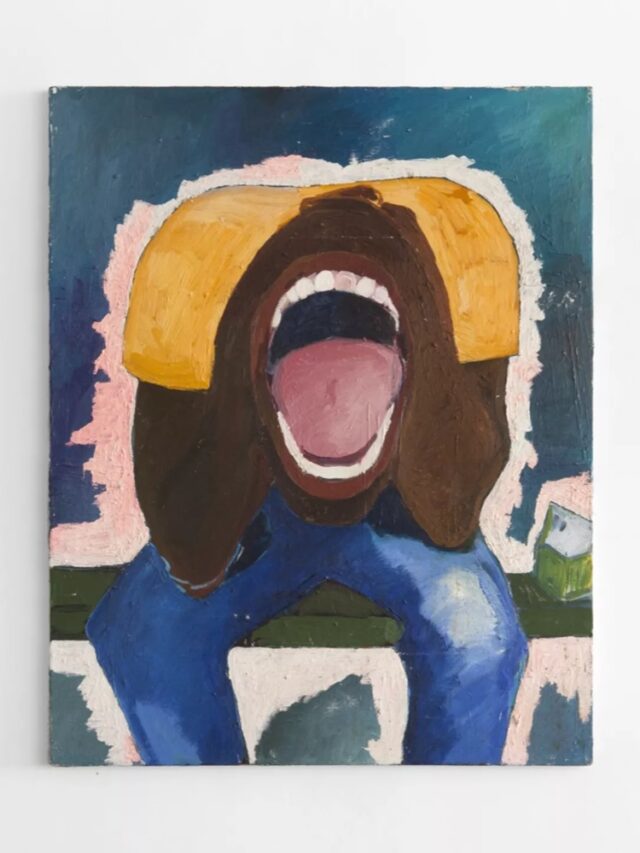

Taylor paints fast and intuitively from memory, newspaper clippings, photographs, and in-person sittings. His paintings are whimsical, personal, and gloomy. He creates paintings that feel alive by blending loose brushstrokes and rich, personal detail regions with flat slabs of robust and sumptuous colour; stemming from a deep-seated empathy for individuals and their lived situations, Taylor’s highly cropped, frequently life-size photos accentuate the visceral presence of his subjects’ humanity, social environment, and mood.

‘Complex throughout, these new works by Henry Taylor desired to be digested and become discussion points about life itself. Taylor creates three particular environments to help trigger memory, show the importance of community, and disturb societal norms to make the viewer present. Being unfamiliar with Taylor’s previous work, seeing this new work as an introduction to Taylor felt fast and full of power. Being introduced to a new idea of home in the first of three spaces, a dirt lot became a shelter. The scene created was so realistic that it felt like being transported to exactly where Taylor drew his inspirations from. Paintings, sculptures, and a new performance with the help of friend Kahlil Joseph; this show makes you question racial inequality, homelessness, poverty, and community and places you in them, writes Nathalia Fagundes.

Based on his own experiences as well as shared history, Taylor provides a perspective on American daily life that is rooted in the realities of his community, including the incarceration, poverty, and frequently fatal encounters with law enforcement that disproportionately impact Black Americans.

In addition to being an artistic creation, Nathalia Fagundes claims that the installation begs the visitor to live inside of it because it seamlessly blends into daily life. The manufactured yet realistic setting is recognisable with Henry Taylor. Snapshots of a dystopian canvas where every perspective becomes engulfed are offered by each area (gallery). Every artwork is more than just a painting. They consist of a narrative, a sentiment, and a screenplay. Henry Taylor allowed me to realise a world I had never experienced before.

Over thirty pieces from Taylor, who describes himself as a “hunter-gatherer” of subjects to paint and materials to make into sculpture, are on display in the new exhibition, ‘From Sugar to Shit’, which highlights his peculiar interest in the world around him. Visitors are greeted with a sculpture of a tree with an afro for foliage on the ground floor of Hauser & Wirth’s expansive new Champs-Élysées site. The sculpture was created from hair swept up from barber shops in Black American areas. Works like “And you thought only we ate chitlins,” a text-based piece, and “For those… who ask, ‘Do you paint white people?” a picture of a lady against a yellow backdrop that has echoes of both Alice Neel and Alex Katz, exhibit this lighthearted, tongue-in-cheek sense of humour.

A recurring motif in Taylor’s conventional portraits is the eyes’ divergence in size, angle, or colour, as seen in “My Great Niece Taylor Watson” (2020) and “A young master” (2017), a posthumous image of painter Noah Davis that shows one eye partially blue as though reflecting light and the other brown. These give rise to a character heterogeneity similar to a “Split Person.” Still, rather than that more specific diagnostic, they could represent opposing aspects of the same personality or concurrently occurring thoughts. He plays with the body to create ambiguous, unsettling effects: hands and feet are excessively big or small; bodies are twisted; limbs are extended or absent, like in the case of “Eldridge Cleaver” (2007), whose legs are oddly angular and truncated.