Horace Pippin is a remarkable person in American art history whose works go beyond simple canvases and brushstrokes to tell a meaningful story about tenacity, identity, and the human spirit. Pippin was born in West Chester, Pennsylvania, in 1888. His early years were characterised by an authentic love of sketching and a natural ability that would come to characterise his legacy. However, there were difficulties along the way to his artistic success. Pippin’s creative aspirations were first postponed during World War I when he enlisted in the illustrious 369th Infantry Regiment, also called the Harlem Hellfighters. It’s possible that his combat experiences, which included a severe injury that left his right arm half-paralysed, discouraged him from pursuing his artistic goals. Instead, they served as a spark for his distinct creative approach, which combined vivid storytelling with reflection.

Pippin’s post-war artistic renaissance was characterised by a resolve to distil his observations and experiences into his paintings. His early pieces, like “The End of the War: Starting Home” (1930), captured the raw emotional intensity of wartime situations and struck a profound chord with viewers. Pippin depicted the psychological and emotional toll that war imposed on individuals who served, as well as the physical reality of the conflict, with vivid colours and accurate information.

During his career, Pippin investigated racial, historical, and contemporary American issues in his artwork. His paintings were groundbreaking and profoundly humanising because they frequently captured African American life with truth and dignity. Drawing from folk art customs and the Harlem Renaissance, Pippin’s style developed into a unique blend of symbolic storytelling and realism. Pippin’s talent ultimately came to light despite experiencing racial discrimination and the difficulties of being a self-taught artist in a largely white art community. A significant turning point in his career was his inclusion in notable shows, such as the 1937 “American Negro Art” exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery of Art. Pippin has a devoted following and critical recognition for his ability to depict the nuances of American life.

Witness of history

‘That attention marked an early manifestation of the suggestion that Pippin’s art is a transparent record of his experience. This enduring trope oversimplifies the relationship between history, memory, and authenticity, which has been critical in establishing and maintaining his place in art. In recent decades, scholars across the interdisciplinary spectrum have worked to communicate the concept of memory as a straightforward, documentary phenomenon.” Of particular value for this discussion is how their efforts intersect with theorizations of trauma and identity formation since Pippin used art to negotiate his place as a disabled African American combat veteran in a segregated society. In that light, how can we make sense of a project like his that is intimately associated with an uncritical faith in the recuperative and aesthetic potential of memory? How do memory, history, and imagination overlap in Pippin’s Dictums, And how were they instrumental for and by audiences of his day? Writes Anne Monohan.

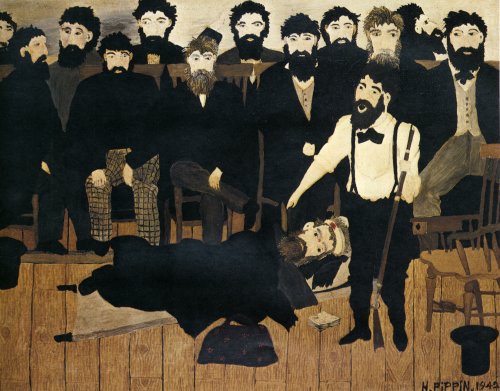

Note Brown Going to His Hanging appears to steer clear of either extreme of that divisive range. With a limited, mostly neutral palette and a severe, ordered composition that controls emotion, the picture embodies restraint. The narrative title and factual approach recall the engravings used to present Brown’s story to a wide readership. Four of such depictions explicitly reference the artwork by Pippin. On December 17, 1859, two were published in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper: “John Brown Riding on his Coffin to the Place of Execution.” From a Sketch by our Special Artist” and “The day before he was hanged, Mrs. Brown escorted mom Harpar’s Perry to the Charlestown call to interview her husband.”

However, Pippin happened onto the pictures, and their application matches his pattern for the complete Brown series, where historical graphics inform the paintings’ iconography and monochromatic colour schemes. The warm tones of an aged print are evoked by the painting’s brown-on-cream colour scheme, which is how Pippin would have probably encountered the image. “It is tempting to imagine that Pippin chose that likeness to suggest something specific about the time of Brown’s moment of inspiration for the slave revolt; however, no information beyond his pa›ntings survives to indicate how the artist educated himself on his sub, etc.”

‘Regardless of the female figure’s displeasure, her expression forges a direct connection with the viewer. I have discussed elsewhere the shift in Pippin’s after his first solo show in 1937 toward paintings that model, in Michael Friedss formulation, theatricality, or figure’s awareness of being viewed, over absorption in their world.” The woman’s outward orientation is an ideal manifestation of the former auality. Of course, when turning to us, the woman turns away from Brown, rendering herself unable to see him, Dass. As a result, John Brown’s Going to His Hanging instantiates a structural tension between art and history: Pipin identifies the figure by showing us her face at the expense of accurately representing her role in history. So, effectively, Pipin commemorates his mother’s Presence at Brown’s execution, an event sometimes regarded as the de facto start of the Civil War’s direct connection to it by constructing a set piece, synthesized from several period sources, in which we witness her (or her proxy) sol witnessing Brown’s last ride, writes Writes Anne Monohan.

Racism and War

During World War II, the most famous Black artist, Horace Pippin (1888–1946), created Mr. Prejudice. His remarkable career path stemmed from the global infatuation during the interwar period with self-taught painters praised for fusing homely topics with abstract form. Their supporters regarded that combination as a means of introducing modernism to a broader public wary of avant-garde politics and tastes. The life narratives of the artists also spoke to the democratic populism that was popular during World War II and the Great Depression. The central theme of Pippin’s narrative was his perseverance following a battle wounded sustained during World War I that left his right arm permanently crippled.

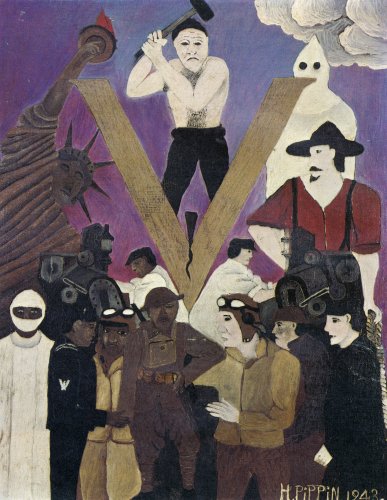

Mr. Prejudice is a smallish painting that depicts racism’s danger to the military endeavour in a style akin to a heraldic symbol. The central axis is occupied by the titular Mr Prejudice, whose large V he digs a wedge into, and his pristine white skin signifies his symbolic standing. This specific V, widely recognised at the time as a symbol of Allied Victory in World War II, is the same one that appears on the Civil Defence certificate that is displayed as a “badge of honour” in windows across the nation. Pippin chose to replace the crimson letter with khaki to avoid having it overshadow his appearance. Mr. Prejudice is flanked by a White guy, a Ku Klux Klansman, and a somewhat eccentric Lady Liberty, who is portrayed as the untainted copper she once was.

Pippin organised that convoluted corporation with a grid, emphasising his idea by placing the V’s split at the geometric middle of the painting. He divided the composition in half horizontally, dividing gods and humanity between the larger-than-life allegorical figures above and the humans below. He divided the statistics vertically according to skin tone. He then depicted the racially divided military and defence sectors in art and illustrated dissent in real life. The V he floated over this arrangement, overlapping the hood of the Klansman, Mr. Prejudice’s legs, and Lady Liberty’s arm, visualises the distance between triumph and systemic prejudice.

Because of Mr. Prejudice’s positive response, people have been inclined to associate Pippin’s participation in the racially segregated American Expeditionary Forces during World War I with the painting’s critique of prejudice in the war effort. Some have gone so far as to read the Black Doughboy in the centre foreground as a self-portrait or, more remarkably, as his stand-in, extending that autobiographical interpretation. To further complicate matters, Pippin chose to honour the bravery and sacrifice of the unit known as the Harlem Hellfighters while remaining silent about the racist treatment of his all-Black troop, the highly decorated 369th Infantry Regiment, in his war memoirs and other writings.

Conclusion

The influence of Horace Pippin goes well beyond his creative output. His life narrative inspires tenacity, inventiveness, and the ability of art to break down barriers. As we examine his paintings more closely, we find a profound reflection of the human condition and a visual narrative of a turbulent time. In this article, we shall look at Pippin’s essential works, the development of his style, and the cultural importance of his contributions to American art.